I caught my daughter reading my journals. I don’t think this was unusual, though I never read my mother’s journals. I knew where she kept them, but I didn’t read her journals because I realized I’d rather not be privy to all parts of my mother’s life. Her ex-husband read her journals. It was a terrible betrayal, hence the ex.

Natalie Serber is teaching a writing workshop specifically for women our age that helps bring out your stories. This weekend, Oct. 9-11. Click here for all the details.

I do recall snooping in my mom’s jewelry box and her underwear drawer (where she stored her pot). I snooped in her handbag. I stole a few dollars. When I was little, age six or seven, she would send me to the corner store with a note, “Please sell my daughter a pack of Winston cigarettes.” Windstorms, I called them. And then I would keep some change to buy an Almond Joy. I am certain I betrayed my mother in other ways, for that is what daughters do, at least the daughters I know.

Friends have told me about trying on their mother’s clothing, rummaging in makeup drawers, opening diaphragm cases, stepping into high heels, massaging their feet with a strange two-headed contraption discovered in a mother’s bedside table. Many friends express joy around trying on their mother’s clothing.

There is happy magic in imagining the future freedom of being an adult. As children, we could not imagine the burdens. Snooping was a way to try and understand the difference between being a girl and being a woman, a way to know better our paradoxical mothers who both offered comfort and mystified. Women we aspired to be just like, or to never be like. Women we sometimes hated, but mostly we loved.

Read More: What I Inherited From My Mother: It Wasn’t What I Expected

Trying on Our Future Lives

My children’s babysitter used to try on my clothing. I did the same thing. I tried on the jewelry and scarves of a beautiful mom I sat for. She was slim, blond, pale, everything Mademoiselle magazine told me a woman should be. Her fancy, reverse-floor-plan home was in the mountains, overlooking a cemetery. She had two adorable towheaded boys and a devoted husband. I felt lucky that she chose me to watch her children. Her life seemed perfect, something to which I aspired. I don’t remember her being particularly interested in me; she just gave me instructions about dinner and bedtime and left in a cloud of perfume.

When our babysitter tried on my clothes, I asked her to stop. I regret that now.

Then there was the night her husband drove me home, drunk. He pulled over beside the dark cemetery and stuck his tongue in my mouth. Honestly, I don’t know what I thought about her life after that. He had daughters from his first marriage, girls who sat in some of my junior-high classes. I thought more about them, and what life with their father was like.

When our babysitter tried on my clothes, I asked her to stop. I regret that now. I should have pretended not to notice, let her try on some other woman’s skin. Because that is what it’s about, right? Girls trying on different lives, imagining who you might become other than your own mother.

But I said something to her, I don’t remember being angry. I just said something like, I know you go into my closet and I would prefer if you didn’t. I may have shamed her, and, now, I feel small-minded and ungenerous. I wish I’d remembered my eighth-grade self in that moment, all the confusion of growing up. How I too sought inspiration and instructions from other sources.

To Keep or To Burn?

When I came home one day and found my daughter reading my journals, I didn’t feel generous or understanding. I felt betrayed, invaded, and like I had no private life. My journal was a release valve, a repository for everything that bewildered me. I spilled my righteous indignation, self-criticism, confusion, and sadness. In my journals, I got to be the raging adolescent acting out, being confused, feeling cheated. I got to be ugly.

When I found my daughter reading my journals, I felt betrayed, invaded, and like I had no private life.

Seeing my teenage daughter with my journals terrified me. Yes, the things I wrote in my journal were true, in the moment, but not my core truths. Would she know that? How could I convey that in a way she would understand? The last thing I ever wanted to do—and ever want to do—is to cause damage. I tried to speak with my girl about it, but I don’t know what she heard or believed.

That day, I took all of my journals, bagged them up, and wrapped the entire package in duct tape. I made a friend promise to destroy them if I was killed in a car wreck, hiking accident, drowning, fire, earthquake, avalanche, you name it. I asked him to please see that the journal bomb be destroyed. He promised.

A friend told me that after her mother’s death, she found her diaries. On the outside her mother wrote, “If found, BURN.” My friend read a few pages and found them so sad that she had to stop. “I realized it wasn’t how she felt all the time, the kind of tortured self-criticism she put herself through was not only reserved for her journals … Complicated, special (in a good way) woman, who fell prey to the notion brainwashed into all of us women that we have to be perfect.” (I fear that notion is also brainwashed into our boys, it’s just that “perfect” looks different for men.) My friend did destroy them.

Re-Reading My Younger Words

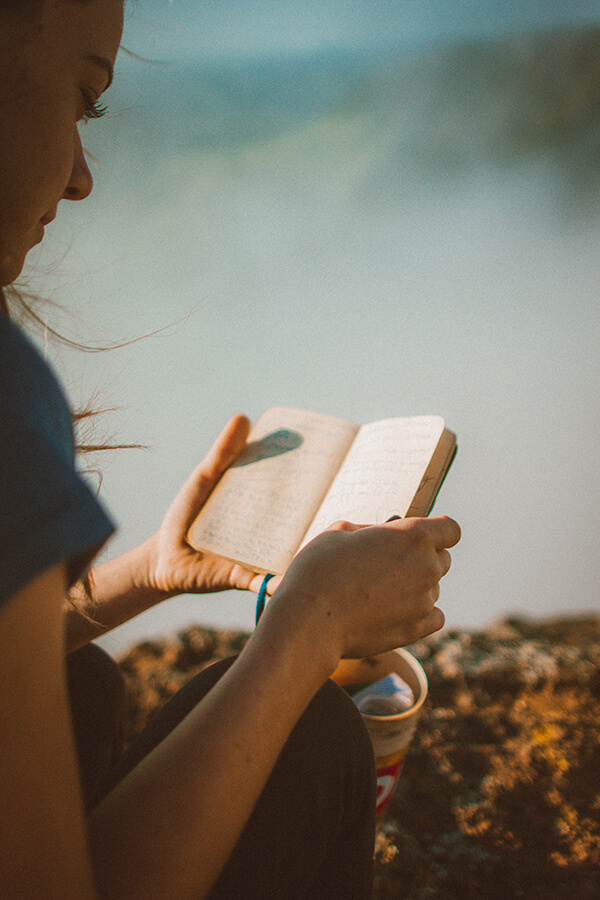

Image: João Silas/Unsplash

Recently I was at a writing retreat, and I brought the journal bomb with me, to burn. It was not that I felt a shady presence, a miasma of emotion hanging about the house all the time—I didn’t. But I did see the bomb every once in a while, on the top shelf of a closet, and I inwardly cringed. You know, the way you feel when you hear your recorded voice? (Unless you’re a rock star or you love your voice and I say, hoorah for you!) But I cringed at the sight of the journal bomb and wanted it gone. Perhaps, too, it was part of being 56. I just wanted to feel lighter of heart. Clearer. Unburdened. I sought reciprocity in relationships, and that fucking journal bomb was giving me nothing. Or so I thought.

It so happened that my cottage at the retreat was equipped with an adorable wood-burning stove. I made a math problem out of it. Thirty-five journals divided by 17 days, so burn at least two a day. Be ruthless!

As I read my journals (honestly, sometimes all I could do was skim), I found plenty of cringeworthy moments, filled with what I hate, how I’ve been injured, my pettiness, the pettiness of others, woe-is-me, I’m a failure, loser, I have nothing to contribute, blah, blah, blah. Many of my journal entries were a cesspool of lizard-brain wallowing that kept me afraid and kept me from writing, from living a more joy-filled life. My journals worried over the exact same criticisms and doubts in 1996 and in 2016! How could I have evolved ZERO in so many years?

I know I’ve mostly done my best. I know my best is sometimes not good enough. But, man, sometimes it is good enough. If my journals tell the truth of a moment in time (and there is no reason it shouldn’t—no one was going to read it, right?), I cannot believe how much time I have spent in the world feeling insecure, uncertain, and not good enough. Rather than sink into more self-doubt, I noted my stuckness and then burned the shit out of it.

My journals worried over the exact same criticisms and doubts in 1996 and in 2016! How could I have evolved ZERO in so many years?

I also discovered some jewels. I know it sounds Sally Fields-ish (“You like me!”), but I found that I really enjoyed spending time with me. Just as Sally Fields was authentically joy-filled when she was recognized by her peers, I recognized that I like a lot of things about the struggling human writing in my journals. I think she’s smart and kind, and I don’t know why she moves through the world with such insecurity. Why she looks outside of her own mind and heart to feel real, to feel verified, and to feel validated.

I found writing advice:

“…the outside world will trivialize you for almost anything if it wants to. You may as well be who you are.”—Grace Paley

Tidbits:

“A slight, acne-scarred boy in my freshman comp. class told me he was a superstar chef. When I asked what about his signature dish, he claimed, in all sincerity, to be an aficionado of ‘toaster cuisine’…hot pockets, English muffins, and pop tarts.”

Quotes:

“No ideas but in things.” I wrote. And then beneath it I wrote: “Who said that? Plato? Aristotle.” And then, BIG mystery, some other handwriting says, “Groucho.” Apparently someone else read my journals too! (William Carlos Williams said it.)

Life advice:

“Suffering does not mean that something is wrong. Suffering gives us the opportunity to touch the limitless space of the human heart.”—Pema Chodron

My journals, from which I will salvage a few prime pages, let me know that the person I am hardest on is me. And that I have an instinct for self care.

Read More: 40 Ways to Celebrate Your Birthday—or Any Other Occasion—Alone

Keeping a Diary: Putting My Past in Perspective

If a journal is a place to say aloud what we have grown accustomed to keeping silent, a place to tell the truth about what we fear is unspeakable, then, when someone reads our private words, are we perhaps uncloaking their unspeakable moments? Are we inadvertently easing universal pain?

It never occurred to me that my journals would be read with compassion, or for insight, and I am so grateful for this lesson.

While reading her mother’s journal, another friend found a cigarette butt taped to the pages. It was a remnant from a man her mother had loved. The friend says, “Longing to hold onto him, preserving daily objects…her grief over the relationship was lifted up. Worthy of preservation…it was heartbreaking and beautiful.” She is learning not only of her mother’s private loss, but her mother’s strength. Another friend tells me she is slowly reading her mother’s diaries now, and what she is learning is filling her with so much compassion.

It never occurred to me that my journals would be read with compassion, or for insight, and I am so grateful for this lesson. I am also briefly conflicted regarding the burn. But only briefly.

The artist Louise Bourgeois kept a drawing diary in which she worked through bouts of insomnia. “Each day is new so each drawing—with words written on the back—lets me know how I’m doing. I now have 110 drawing-diary pages, but I’ll probably destroy some. I refer to these as ‘tender compulsions.’”

In September 2007, I wrote: “It is precisely the conflicted feelings within us that make us human. Exploit and explore these. Be generous, with yourself, with your characters.” I think, by destroying my journal bomb, my own “tender compulsions,” I am being generous with myself. I’m reminded of what I’ve made it through and of what I can let go.

A version of this story was originally published in October 2018.

***

Natalie Serber is the author of a memoir, Community Chest, and a story collection, Shout Her Lovely Name, a New York Times Notable Book of 2012, a summer reading selection from O, the Oprah Magazine, and an Oregonian Top 10 Book of the Pacific Northwest. She lives in Portland, Oregon. Visit her online at natalieserber.com.

0 Comments