One early afternoon on Ashbury Street in 1966—just a beat before the love-drenched, beads-and-Victorian-clothes-wearing psychedelic culture in that slice of San Francisco was about to change America from the Mad Men era to a place of sybaritic idealism—a scraggly-haired, wide-smiling girl opened her second floor window. At the same time, right across the street, a more polished looking young woman, a former flight attendant and the owner of the hip clothing store where all the new rock bands congregated, opened hers.

“Hiya, honey!” the first girl said to the pretty stranger across the street. “Hiya, honey,” the second one replied, hard pressed not to answer in kind. And with that, a four-year friendship-turned-love-affair-turned-back-to-friendship bloomed.

That first girl was Janis Joplin, and she would quickly become one of the most iconic singers in last half century. Her movingly bluesy hits—“Piece of My Heart,” “Cry, Baby” “Ball and Chain” and others—taught suburban white girls that they could aspire to what many wanted so desperately: soul. Her wide, smiling, pleasant but imperfect face said that a female icon could look like you and me. Her boas and piled-on jewels, wide-sleeved blouses, and shiny hip huggers were widely imitated.

She was the female face and spirit of the counterculture, wide-grinning and wild—and, yes, alas, a heroin user—but with a palpable heart of gold. She was also a thoughtful, sensitive, intellectual middle-class girl, an alumna of the University of Texas at Austin and member of the Slide Rule Club in her high school in Port Arthur, Texas. The dutiful daughter of a Texaco engineer and a business college registrar, she wrote her parents weekly from the Haight, her Little Women-like letters started with lines like, “Mother,… I’m brimming with good news.” As her hometown childhood friend, J. Dave Moriarty, put in Amy Berg’s excellent 2015 documentary, Janis: Little Girl Blue, “She got a kick out of playing the bad girl but she wasn’t a bad girl.”

Read More: Cass Elliot’s Daughter on the Crushing Fat-Shaming Her Mother Endured

The Girl at the Other Window

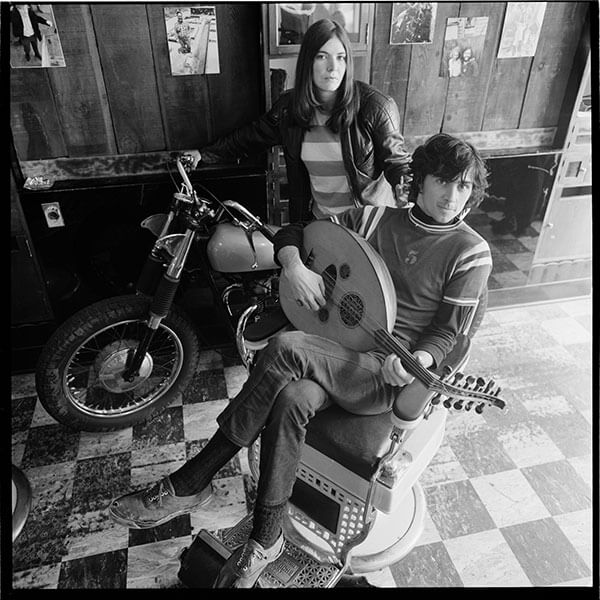

“We were right in the middle of the ’60s,” Peggy Caserta says of this photo (with a sandal maker from her store). “The Grateful Dead had probably just posed for me. 1966 or 1967.”

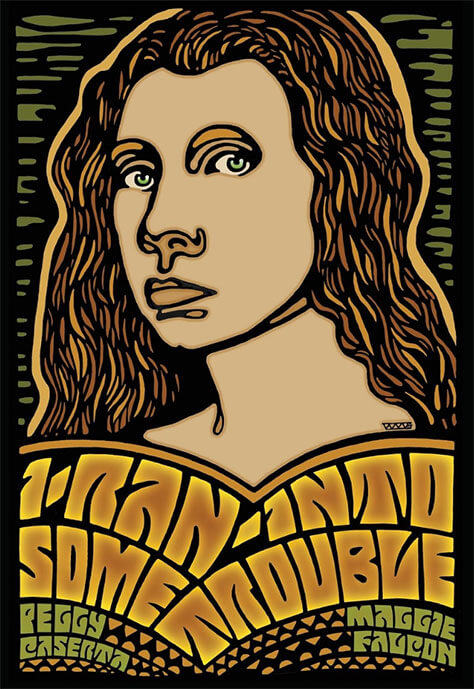

Peggy Caserta was the girl in the window on the other side of the street, and she and Janis would become friends, lovers, and friends again from that day forward. She knew Janis like few others ever did. After keeping silent for decades, she’s written an eloquent memoir, I Ran Into Some Trouble, to be published August 1, about her life with her best friend Janis and life on her own.

Regarding the title: Peggy admits she did heroin with Janis—and she later drove a getaway car for imprisoned friends. But she was also a high school homecoming queen and made millions designing innovative clothes for rock stars that mightily influenced fashion—and she brought the idea of bell bottom jeans to Levi Strauss. Caserta is also a main consultant on the 22-years-in-the-planning major theatrical biopic of Joplin, which will star Michelle Williams and is supposed to start production in August.

Here, we get a several-months jump on revelations from Peggy’s book as we talk about the Janis her fans didn’t quite know.

Q: After the window hello, how did you actually meet Janis?

A: I went to see her at the [local club] the Matrix—and her singing of “Bye Bye Baby” nearly knocked me out of my chair. I went up to her afterward and said, “You’re gonna be a superstar,” and she laughed that funny laugh and said, “You really think so?!” Cut to five days later. She happened to come into my store, Mnasidika, and wanted to put a pair of jeans on “layaway”—for 50 cents a week. I was touched by that, and I said, “Go ahead, just take ‘em.” She looked at me wide eyed and said, even more earnestly, “But that would be stealing. Won’t you get fired?” I loved that! A few days later she came back into the store and said, “Aha, you’re the owner!” That started our friendship; she loved that I was Southern, like her. She thought that gave us a connection that she didn’t have with the other girls who’d come to the Haight, who came from “the East.”

Q: You had a very difficult girlfriend at the time, right? And Janis, as your friend, helped you deal with her?

A: Yes, Kimmie was abusive—physically and emotionally. Janis would say, “Peggy, why do you take it? You shouldn’t take it!” Janis was compassionate.

Janis had a goodness to her. And a homeyness.. After she became famous we’d be together at one of the hotels with the guys in her band and she’d say, “Let’s make the boys something to eat.” And I’d say, “I’m not making them shit. You pay them enough money—let them go get their own hamburgers.” But she had this homey thing about her. She always wanted to fix them soup. It was a hoot—two of them were on heroin; they didn’t want soup!

Not a Traditional Lesbian Relationship

Q: I know you’re a proud lesbian. You’re gay, and you always have been. But, even though you were lovers, you say that Janis was not gay.

A: That’s right. Janis and I never got into a traditional lesbian relationship—“Hi, honey, I’m home…” She was always going to please her family and get married. Pleasing her family was very big with her. Her mother and her father and her brother and sister—she always spoke of them with respect. We did become lovers for a while, but I’ll go to my grave saying that Janis wasn’t gay. She would talk about finding the right guy. She fell for Country Joe McDonald, and one night when she thought he stood her up, she came to me crying her eyes out. But he honestly didn’t realize he had a date with her that night. She was vulnerable.

Q: Yes. Didn’t you say she got very emotional when you called her “beautiful”?

A: Yes. She had lost weight around her face, and one day I looked at her and said, “You are beautiful, Janis,” which I thought she was. She burst out in tears. She had been very injured about her looks. She had had a horrible thing happen to her in college—the boys voted her “Ugliest Man on Campus.” Not even “woman,” which would have been bad enough. But “man”? I mean: What school would even let kids have that category?! It was something that stayed with her and hurt her for a long time.

So, yes, she was vulnerable, but she was also wild. Wild, wild, wild! She had a “Cast it to the wind” way of living. Janis was both strong and vulnerable—talented but modest and humble about it

Read More: The Eve Babitz Resurrection and Other `Forgotten’ But Cool Women Who Deserve a Revival

Vulnerable and Wild

Q: A complex person. And she was a heroin user.

Yes. The heroin, which we did together—it bonded us. As I phrased it in the book, “This is not easy to say since heroin ultimately leads to such pain and loss of control, but we did it because we enjoyed it. It made us feel hip, along with soothing all the pain of life. Gone [with the heroin] were some of Janis’s deeper fears. It was also a way to come down from the incredible adrenaline surge and palpable energy slam that hits artists performing in front of thousands of fans.”

Q: And she was sometimes vulnerable about her singing, right? And her stardom?

A: Yes. She’d sometimes say, “Wait ‘til they find out that I can’t sing.”

Q: Ha! Listen to her sing “Summertime” or “Piece of My Heart” and put that to rest.

A: She worried that she would be fired from Big Brother and the Holding Company. Right after she said that, Wes Wilson [a big poster artist at the time] re-designed the posters so they weren’t “Big Brother and the Holding Company” but “Big Brother and the Holding Company” with “Janis Joplin” in huge letters.

Q: So she was insecure enough that didn’t see that was coming.

A: Right! But she also had her diva side, after she got famous. Her diva side and her humble Texas girl side, both.

Q: A nice combination.

A: Yes. And in the same night.

One night, after she’d become well known, we were at a hotel in L.A., and she became hungry in the middle of the night. She wanted Greenblatt’s [a local deli] to deliver. I said, “It’s 3 a.m.!” She said, “They deliver to stars at 3 a.m.” I said, “Well, well…so you think you’re a star.” It turns out they didn’t deliver at 3 a.m., even to stars, so I took her walking down to Hughe’s Market, and I saw her holding two jars of grape jelly, comparing the prices. I tapped her on the shoulder—this “star” (which she was)—and I said, “Um, honey, your days of having to worry about spending 30 more cents for a jar of grape jelly are over. Get the more expensive one.”

On To Woodstock

Q: There are famous pictures of you and Janis at Woodstock. Can you tell me about that epic experience?

A: It was spectacular. We had just helicoptered in, and we were standing on the stage together and as far as you could see there were people—it was biblical in scope. No one had ever seen anything like it! Even Michael Lang [one of the organizers] was hoping for 50,000 people, but there were 400,000. And Janis looks out and says, “Oh, my God! Do you know what this means?” I thought it meant, “Yes. You can sell a lot of records.” But she had something bigger and nobler in mind. She grabbed my hand and said, “For every one of these people out there, there had to be at least ten who couldn’t make it. We could throw an election—we could put in a new president!” She was thinking about the political culture. She wasn’t just thinking of herself.

Q: Those peace-and-love days, those antiwar days, that fierce idealism: They were long ago. Today we have a group of Millennials with amazing reach and commitment—#MeToo, March For Our Lives. Do you think—two generations later—this activism is something new, or a continuation of what you all in the Haight helped start?

A: I hope we started something that made a difference. We certainly put a lot of passion in it.

Q: Tell me about some of the zany, fun times you had with Janis.

A: Once we were driving to the San Diego Zoo, from L.A., and we were so stoned, we took a wrong turn and got ourselves almost back to L.A. But maybe the funniest time was when we went to Serendipity [a chic ice cream parlor on New York’s Upper East Side] in the morning. That was Janis. She wanted ice cream in the morning. We were sitting there, and I said, “I don’t like the name Peggy. I’m going to change my name to a floozy name, Ruby.” She said, “I’m going to change my name, too: to Pearl.” [That did become Janis’s nickname and she had a major album of that title.] I said, “Well, I said it first! And I’m not gonna do it if you do it because they’ll think I’m copying famous you!” And we’re arguing like silly teenage girls! Meanwhile, she’s looking at the New York Times (Janis always read it in the morning). And, as if by magic, she opens it up to a big centerfold ad for a stenographers’ school that featured two longtime workers. And what were their names? Pearl and Ruby. We cracked up.

Q: So it was fated.

A: It was.

Losing Janis

Q: But something else wasn’t fated. Her death [on October 4, 1970] has officially gone down as an overdose by way of heroin. But you think it wasn’t.

A: That is right. She was at the Landmark Hotel in L.A. She had a pack of cigarettes in one hand and the change from buying the cigarettes in her other hand when she was found, face down, between the two beds in the room. There was no needle in her arm or in her hands. She was wearing these little sandals with hourglass heels, the kind you can easily trip on. And she was stoned. The shag carpet was very, very old and loopy, the kind that can catch in a shoe. I believe she was asphyxiated. A recently interviewed coroner on Reelz TV believed that it also was asphyxiation because her head was turned one way and her body the other.

Q: When she died—at the peak of her fame, at 27!—did she realize what an influence she’d have?

A: I think she was beginning to. She realized she was influencing style. She realized she was influencing white girls who wanted to be soulful. She was happy about that.

Q: And what do you miss about her?

A: [SIGHS] Oh, honey, I miss somebody making me feel wanted! I miss someone who was always so happy when I showed up! It’s 47 years later, and when I’m in the car and one of her songs comes over the radio—I think “Me and Bobby McGee” was her favorite—well, it’s like she’s with me, in the car.

We had some really fun times. I miss her so much.

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

A version of this article was originally published in May 2018.

0 Comments