Editor’s Note: With the news that Eve Babitz has passed away at 78, we are re-publishing Sheila Weller’s 2019 in-depth look at the writer/provocateur who was recently rediscovered by the younger generation.

***

I remember Eve Babitz when she published the little-known Eve’s Hollywood—and then L.A. Woman and Sex And Rage—in the 1970s.

I was a young woman from West L.A. living in Manhattan, so my city of origin was why I knew enough to read Babitz’s oh-so-cool dispatches of her effortless immersion in sexy decadent 1970’s LA. I read those books with a mixture of extreme envy—entranced with Babitz’s own obvious self-entrancement—and slight, gratifying disdain for her brazenly paraded superficiality.

Babitz was so provocative, your teeth ached.

Babitz was so provocative, your teeth ached. At 20, she played chess with Marcel Duchamp totally nude (she was extremely large breasted), and the Julian Wasser photograph of that event was iconic—today it would be viral. But there was no “viral” then, other than for communicable diseases.

Babitz wrote to Catch-22 novelist Joseph Heller: “I am a stacked eighteen-year-old blond on Sunset Boulevard. I am also a writer. Eve Babitz.” He wrote back in a nanosecond and got her publishing connections. She had affairs with everyone, from artist Ed Ruscha to musician Jim Morrison to actor Harrison Ford to writer Dan Wakefield.

Her prose was luscious, romantic, and slightly poor-you-for-not-being-me. But she was also clearly an ambassador, a cheerleader. The attitude, There is no place as cool as this world of mine, was almost a little too charmingly head-forward in those coolly esoteric, self-promotion-is-for-assholes days. Now, of course, we’re in the everyone-is a-Branded-Entrepreneur era, but back then Eve Babitz was a brand … waiting for branding to exist!

Her family life gave lie to the tedious cliché of the city’s *eye-roll* Lack of Seriousness. Babitz’s father was a concert violist; her godfather was Igor Stravinsky. Kenneths Patchen and Rexroth both hung out in her living room, as did Arnold Schoenberg. Babitz grew up in a world of hipness that circled from art to classical music to movies to surfing, with the hedonism that formed the title of her second book: Slow Days, Fast Company.

But Babitz and her books didn’t make a dent—not in New York and not in the literary and cultural worlds. No Fran Lebowitz was she. No Joan Didion (though Joan was a friend of hers). Her books traveled pretty quickly to remainder bins.

Now all that has changed!

Finally, Cult Status

Lili and Eve. Image: Courtesy of Lili Anolik

Today Eve Babitz, age 75, is all the rage. Her once-mothballed memoirs and novels are big sellers among younger women. She has attained cult status with the Lena Dunham crowd. How did this happen?

A few years ago, Lili Anolik, a now-40-year-old contributing editor for Vanity Fair, “discovered” Babitz. Having read her books in 2010, Anolik, like a besotted groupie, established contact with the people around the reclusive Babitz. When Babitz finally agreed to meet, Anolik flew from New York to L.A. the next day. Anolik’s 2014 Vanity Fair piece—which featured the shocking fact that Babitz had suffered burns over 90 percent of her body when, in 1997, she tried to light a cigar while driving her car—jump-started an Eve Babitz revival: Babitz’s books were re-reviewed by Dwight Garner in the New York Times and republished by the New York Review of Books Classics, whose managing editor Sara Kramer has decreed, of Babitz: “Her time is now.”

A Biography of Her Own

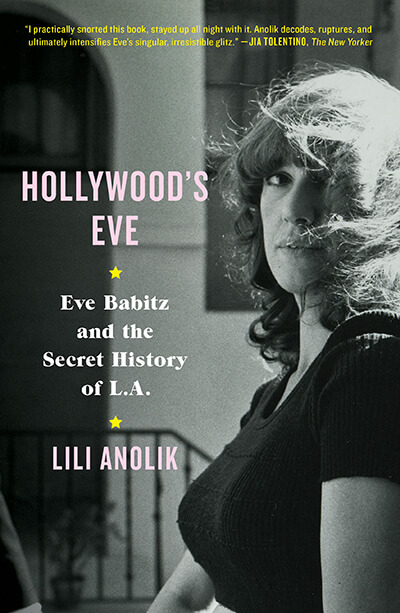

Now Anolik’s own book, with its wittily flip-flopped title—Hollywood’s Eve—has come out, and it’s intensifying Babitz’s belated icon status. Anolik’s book is getting raves. Jia Tolentino wrote, in the New Yorker: “I practically snorted this book, stayed up all night with it. Anolik decodes, ruptures, and ultimately intensifies Babitz’s singular irresistible glitz.”

I read Anolik’s delicious book in one page-turning sitting, and, after all the cocky sex and fun name-slinging, I was stopped in my tracks by the severity of Babitz’s 1997 accident. She had “spent six weeks in the ICU, several months after that in a rehab hospital” and “survived two twelve-hour operations” that were mind boggling for how many parts of her body they affected. Babitz has earned her rediscovery. “Eve didn’t fail to mature; she refused. … Every time life tried [to mature her], Eve blocked or parried, danced away laughing.” There was zest through the book and sobering sadness at the end.

If anyone seems contrary to the #MeToo moment, it’s Eve.

Reaching Anolik as she was flying out to promote her book and hang a bit with the infirm Babitz, I asked her, “Why Eve now? And why with younger women?” She answered: “If anyone seems contrary to the #MeToo moment, it’s Eve. ‘All I cared about anyway was fun and men and trouble’—that’s what the Eve stand-in says in L.A. Woman. She was more or less ignored during her actual career, in the post-Pill, pre-AIDS, anything-goes ‘70s, when her sensibility and the sensibility of the times were simpatico. The ‘70s were an id time, so Eve, id incarnate, wasn’t necessary. But now that we’re in super ego times, she represents the perfect antidote.” I think Anolik’s theory is spot-on.

I asked Babitz, through Anolik, how it feels to be an all-the-rage writer all these decades later. The former man-magnet answered: “When I was young, it was only men who liked me. Now it’s only girls.”

Why Now?

Indeed, there was something about those crazy, wildly politically incorrect years—and the women who found a way to conquer or ignore the chauvinism and have a great time, anyway—that is perhaps a relief and weirdly hopeful sign to women who otherwise devour Rebecca Traister’s excellent and important Good And Mad and are super alert to every new man accused of past harassment. Many midlife and older women remember at least some version of those non-PC days that were lived—and hyped up—to the extreme in Babitz’s accounts. “I was twenty three and a daughter of Hollywood … wanting to fuck my way through rock ‘n’ roll and drink tequila and take uppers and downers,” she wrote. “I’d always believed that sex masterpieces were the best kind … better than Bach, the Empire State Building, or Marcel Proust.” If today’s serious feminist times need a big fat mothereffer of a vacation, complete with liquored fruit drinks, here in this rediscovered brazen writer is the very thing!

Indeed, there was something about those crazy, wildly politically incorrect years—and the women who found a way to conquer or ignore the chauvinism and have a great time, anyway—that is perhaps a relief and weirdly hopeful sign to women who otherwise devour Rebecca Traister’s excellent and important Good And Mad and are super alert to every new man accused of past harassment. Many midlife and older women remember at least some version of those non-PC days that were lived—and hyped up—to the extreme in Babitz’s accounts. “I was twenty three and a daughter of Hollywood … wanting to fuck my way through rock ‘n’ roll and drink tequila and take uppers and downers,” she wrote. “I’d always believed that sex masterpieces were the best kind … better than Bach, the Empire State Building, or Marcel Proust.” If today’s serious feminist times need a big fat mothereffer of a vacation, complete with liquored fruit drinks, here in this rediscovered brazen writer is the very thing!

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

0 Comments