It’s tough to cover the second-wave feminist movement of the early 1970s in a way that is both amusing and genuine, while at the same time incorporating a montage of full-frontal dongs. (If you object to the d-word, which pops up a lot on the show, perhaps you’d prefer another of the show’s favorites—“schvantz?”)

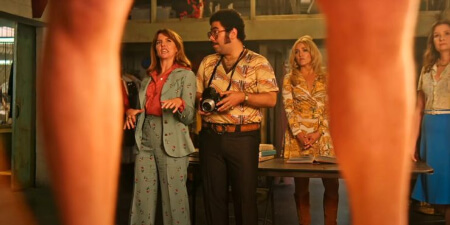

But that’s the task Minx, the new 10-episode series on HBO Max sets for itself. Written and produced by Ellen Rapoport, Minx starts out in 1971, with overtones of Mrs. America, GLOW, and The Deuce.

Except that this is a meet-cute comedy featuring a recent Vassar graduate—a young priggish feminist named Joyce Priggers. (The terrific actress’s name is even better: Ophelia Lovibond.)

The Endless Anger

With her prissy, high collared blouse, Breck girl hair, and three-piece pantsuit, Priggers shows up at a Southern California Magazine Convention “pitch-fest.” (did they even have those in 1971?) She’s trying to sell her passion-project, a high-minded feminist magazine she calls, The Matriarchy Awakens. (Ms. would come out one year later.)

While waiting in line, Ms. Priggers intercepts a nasty plume of cigar-smoke puffed by the leisure-suited dude behind her, an operator named Doug Renetti. He’s grounded in the business, with a stable of successful publications like Giant Jugs, Feet Feet Feet and High Heel Hoochies.

Are erections consistent with our philosophy?

Joyce complains about the smoke and goes inside to pitch. Unfortunately, her presentation goes nowhere: the old white men who are the judges are delighted by the covers she’s showing as examples of blatant sexism, and are threatened by her Matriarchy Awakens cover, featuring an open-mouthed female protestor in aviator glasses holding up a poster. One of the men asks, “Why is she so angry?”

And this is one of the best lines in one of the best scenes in the show, because sadly, some 50 years later, it’s still reverberating.

Read More: Telling the Story of Women’s Rights, The Glorias Recharges Feminist Batteries

The Minx is Born

Joyce is disheartened by the response, and it turns out that sleazy cigar-smoker Doug is the only publisher who can see something in her idea. He tells her that she’s got to find the “peanut butter” for the magazine—meaning that if you need to give a dog a pill, he’ll swallow it if it’s covered in peanut butter. So for Matriarchy Awakens, he proposes an attention-getter that’s never been done before in a woman’s magazine: a nude male centerfold.

And thus, with its name changed to Minx and its nutty phallic core, the first erotic feminist magazine is born. Along the way, Joyce regularly voices questions like, “Are erections consistent with our philosophy?”

Doug reassures her, “Well, it’s not like a shvantz right in the face.”

They are a classically unlikely pair. As Katherine Hepburn supposedly said about Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, “he gave her class and she gave him sex appeal.” The Joyce-Doug merger is the opposite: she gives him class and he gives her sex. Not physically, though. Doug has a gifted girlfriend/secretary, Tina (Idara Victor), one of the only Black characters on the show, whom Joyce manages to offend on her first day.

The “Lighten Up” Problem

Still, separating sex from issues of female empowerment is not easy, in real life or fiction. For all of its enjoyable banter and energetic cleverness, one of the problems with the show is that we have a protagonist who is at war with herself, who seems to need to “lighten up” (ugh) and learn a lesson. She really does come off as a scold, which was and still is a built-in criticism of feminism.

By contrast, Doug the porn publisher (played by Jake Johnson) is a laidback wonder with a heart of gold. A very enlightened guy for his time, Doug sees a new market that he wants to cash in on, and says feminism is about “making shit fair and equal for the chicks.”

These days, HBO and streaming TV services seem to be all in on the proposition that “penises are having a moment.”

Throughout, the sets and costumes are pure ‘70s fake gold, with the pattern-y polyester, shag rugs, and platform shoes to prove it.

In the constant tension between them, Joyce calls Doug a “tacky salesman with a cheap gimmick.”

The gimmick part could be said of this series, too. These days, HBO and streaming TV services seem to be all in on the proposition that “penises are having a moment.” It turns out that just as the fictional magazine has its centerfold, the show itself sports a mildly shocking centerpiece, a longish video montage of floppy dicks, (with many variations in size and appearance, some doing tricks) set to the music of Mr. Big Stuff.

And it works. No less an august publication than The New York Times chose to cover the casting and production of that scene, in which male models with realistic ‘70s -style non-grooming habits drop trou and reveal all. The Times quotes one of the actors saying, “I was the first one to show his cannoli.”

Going With the Male Centerfold

I myself was never in the camp that objectifying men was the answer to the objectification of women. But I liked the way the writers incorporated a bit of actual publishing history from 1972, when Cosmo came out with a naked Burt Reynolds as its first male centerfold. With very warm lighting and Scavullo behind the camera, Reynolds is shown propped on his side, lying on a bear skin rug in all of his hairy glory, with one of his hands artfully covering his junk. It was a huge success because it was just revealing enough, a titillating joke about hypermasculinity that both Burt, the magazine, and the readers were in on.

Whereas Playgirl, which published graphic male nudity between 1972 and 1973, was never as successful with women but did reportedly capture a gay male following.

I myself was never in the camp that objectifying men was the answer to the objectification of women.

Another thing the writers get right: decades rarely begin or end on schedule. They show that in this Nixon era, the country was divided, by the Vietnam War, of course, but also, late 1960s progressive values were beginning to infiltrate the prevailing, conservative 1950s-style morality, and prejudices.

And with the advent of the pill, there was a sexual revolution, but newly working women faced sexual harassment in the office and rigid gender roles at home.

To get a sense of the throwback mores of the time, the Mary Tyler Moore Show debuted in 1970, presenting a single, working woman, a revolution in a pants suit, who can throw her hat in Minneapolis and “might just make it after all.” Yet network standards forced the writers to give her a “broken engagement” as her backstory, rather than a divorce, so she could still seem virginal.

This is rich turf for Minx to explore.

In the second episode, Joyce and Doug move on to selling ad space, and it’s their familiar tug of war—she toward classier advertisers, he relying on the same smutty lineup of clients selling various sexual paraphernalia he has for his other titles.

The Anachronisms

I must say that Doug’s employees are mostly wacky and wonderful characters (and fabulous actors) who seem to be as woke as time travelers to the 2019s might be.

For that matter, anachronisms, there are a few.

The term “women’s lib” is never mentioned, although that’s what people called it then.

The language is more modern than it should be. The term “women’s lib” is never mentioned, although that’s what people called it then. And while Priggers talks about the “patriarchy” and “misogyny,” we never hear the hoary old phrase that newly enlightened women then called men: “male chauvinist pigs.” For that matter, no one mentions “consciousness raising.” Instead, the writers use a lot of contemporary terms like “sexual agency,” and “sex-positive.”

Doug says something is a “little bit shame-y” which then was not an understandable choice of words, but I suspect the twenty-somethings watching won’t notice.

And in doing this, I’m beginning to sound as scold-y as Joyce.

As Doug says of humans, “We are not one thing.”

Overall, Minx is an ambitious concept, clever enough to keep me watching. Although it’s depressing to consider all the ways that women have not necessarily come a long way, I’m excited to see where it goes.

0 Comments