On only my second day traveling the Amazon River, I admit, I was getting cocky. The storied jungle had yet to produce a single peril. There was no colossal snake, poison dart, or maggots embedded in flesh. We were hiking inside a lush moss-green shroud, a day’s journey by boat from the closest village that had motorized vehicles. The treetops blotted out the sun, and we sweated in the claustrophobic stillness. Each of all of us was soaked in DEET, the carcinogenic repellent needed to ward against malaria and dengue-fever carrying insects.

“I’ve seen more mosquitoes in the forest in upstate New York than I’ve seen on this walk,” I cracked. Within seconds of my utterance, a cloud of the pests materialized around the head of our guide, a shaman-ically trained Indian, fanning out from that point to attack exposed flesh.

In the instant of stepping forward, the golden eye blinked open and met mine, and I knew what would happen next.

Slapping, scratching, and spraying on more repellent, my fellow hikers had just finished cursing me for calling them forth, when a local villager with a machete on his belt stepped out of the tangled shadows to present for our amusement a yard-long anaconda neatly coiled around the end of a large stick. The serpent was utterly still, apparently sleeping, and I decided to venture behind it for a photo op. In the instant of stepping forward, the golden eye blinked open and met mine, and I knew what would happen next. The creature darted to strike, missing me by inches.

My drawers stayed dry, but just barely. It doesn’t take long for the jungle spirits to humiliate society’s day-trippers. Chastened, I resumed walking with the group along the muddy path in synthetic, quick-dry gear. It was easy after that to envision the forest goblin the Amazonians call the curupira—a small, hairy, ugly little man who sleeps in the great buttressed tree roots—smirking from a shady perch. Natives believe the curupira’s feet face backwards, the better to leave misleading footprints to lure his prey—the disrespectful outsider—deeper into the woods.

Traveling the Amazon River: The Land of Mirrors

The jungle is lovely, dark, and deep. And oh, the greens. There are 65,000 tree species in the Amazon, some still nameless, and each with its own shade of verde, on a spectrum from emerald to chartreuse, and its own world of insect and fauna. Trees in the legume family drip giant peapods, the coffee-related cecropia tree produces green gummy worms of sugary seedpods, and the majestic white kapok dangles large red pepper-shaped fruit like Christmas ornaments. The ground is alive with moving bits—leaf cutter ants endlessly hauling chopped foliage to their nests where they will masticate, spit them out, and farm a fungus on which they feed themselves and their young.

The Delfin II on the river.

For seven days, we—two dozen souls on a riverboat —would drift in a Lindblad Expeditions National Geographic riverboat boat called the Delfin II, on mile-wide muddy waters, exploring often nameless tributaries, and occasionally hiking in the rainforest of Peru’s Pacayo-Samiria reserve. Known as the land of mirrors, the glassine floodwaters here reflect the sky, turning the world surreal hues of violet and pink at dawn and twilight. It is a birder’s paradise by day, the air and trees filled with shrieking streaks of gold, indigo, and crimson. Trees crawl with monkeys—and creepy insects. The jungle floor also produces numberless natural medicinals, from the shamanic spirit drug ayahuasca to cures for malaria, diarrhea, and maybe even cancer.

The Amazon Basin is the largest tropical rain forest in the world still mostly as Nature intended. Of course, Nature’s intentions are rarely, if ever, in synch with what humanity wants. We love Nature’s gifts of gentle breezes, babbling brooks, flora, and fauna, and yet we are perpetually at war with all of them, from storm to flood to predators large and microbes invisible.

I’ve spent a good part of my own life at war with Nature. Aside from a few childhood years cavorting in the wetlands of Michigan, I have avoided Nature’s course by artifice, medicine, and good luck. No accidental pregnancies for me. No hairy armpits either. Now, in middle age, the inexorability of Nature hits home, and hard. After years of looking much younger than my age, there can no longer be any pretense that my face and body will not succumb. Half of my friends have survived breast cancer; friends from high school have begun to die. My dad has survived a diagnosis of prostate cancer, and we almost lost my mother to heart disease. I was lured to this place by its exoticism and beauty, but entering the jungle also meant tearing away the polite screens of modern existence and facing the cycle of life and death head-on.

The Mythical Man of the Forest?

We entered the mighty Amazon River in darkness, from a muddy port town called Nauta, an hour and a half bus ride from the nearest airport. After arriving at the dock, the bus wheels sank into red muck. Stray dogs scampered in and out of shadow and families tucked into Sunday dinners at tables perched in mud outside wall-less thatched huts.

Stray dogs scampered in and out of shadow and families tucked into Sunday dinners at tables perched in mud outside wall-less thatched huts.

After our first night aboard the Delfin II, we were awakened by knocks on the door at 5:30. Every morning for seven days we would hear the same knock, inviting us to rise and go out exploring on a small skiff. By 6:00, we were on one of the Amazon’s tributaries, the Maranon, an Indian word which means cashew. In the dawn light, the water was a sickly pinkish brown, reflecting the sky’s washed silver blue streaked with rose. Black-collared hawks wheeled, the three-toned whistle of the colorful toucan rang across the water, and and two pairs of red and blue macaws, which live 100 years and mate for life, soared overhead.

We turned from the main waterway into one of the narrow, nameless tributaries, where black water (yanayacu), stained by the tannins of rotting vegetation, lapped halfway up the trunks of vine-choked trees. Squirrel monkeys, travelling in troops of up to 300, scampered in branches, their upturned tails silhouetted against the sky. I later spotted a few of these animals for sale at the market in Iquitos, the largest town in the region. Locals prize them as house-pets because they eat roaches and other insects.

The banks were lined with towering, large-leaved cecropia trees, a plant so suited to the river basin environment that it grows 8 to 12 feet annually. Each tree hosted its own ecosystem. Vicious azteca ants creep along the bark, feasting on nectar that oozes from the leaves. Colorful tanagers feed on the ants. A brown, still clump high in a high branch, examined through binoculars, turned out to be a three-toed sloth. We would see a lot of these strange, sleepy creatures—resembling faceless small men—dangling from tree branches, gorged on leaves, literally drunk on leaf alkaloids. The early Amazonian explorers, spotting these homunculi, could easily have imagined them to be the mythical man of the forest.

El Dorado and The Lost City

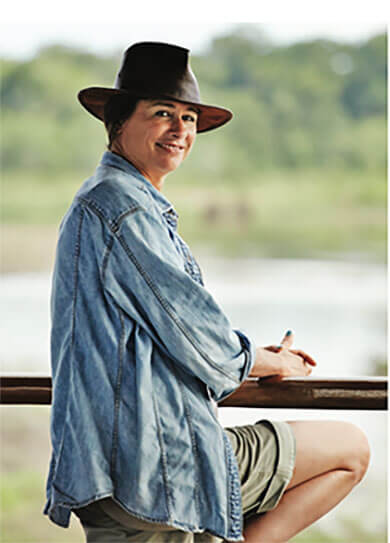

Nina on the Delfin II. Photo credit: Adrian Gaut

The story of the discovery and exploration of the Amazon is a story of death, disease, and greed. Francisco Pizarro, the conqueror of Peru, obsessed over a rumored jungle town made of gold called El Dorado. His half-brother Gonzalo set off in search of it, in 1541, with a legion of iron-clad conquistadores and 4,000 enslaved Indians. Setting off from the Andes, they traveled eastward.

Within a year, the expedition disintegrated, ravaged by disease, hunger, and Indian attacks. More expeditions followed, meanwhile the native population was decimated by European diseases to which it had no immunity and by genocidal brutality that continued into the early 20th century.

Today, a few wild tribes do still exist deep in the jungle. One was the subject of a book by Scott Wallace, The Unconquered, about a modern-day expedition, aimed at finding and protecting the last “unconquered” wild Indians deep in the rainforest. Even with sat-phones and GPS, the modern-day explorers got lost and faced hunger, subsisting on monkey meat.

The mystery of the Amazon, which seduces, then kills, outsiders,remains as strong today as ever. David Grann’s The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, made into a movie starring Charlie Hunnam, chronicles the enduring—and still completely unproven—belief that a fabulous, sophisticated culture once existed deep in the jungle, whose ruins might still be found. Grann describes the mind-boggling rigors of doomed explorer Percy Fawcett’s various expeditions and those of dozens of later explorers who went looking for him, only to die themselves.

The Struggle to Endure

As upper-middle class 21st century “explorers,” we would face no such hardships, but all of us were in search of our own jungle grail. For many of the passengers it was the myriad bird species. But after I’d seen a few sloths, monkeys, and toucans, I grew much more curious about the human inhabitants and their elemental struggles to endure.

Shedding the weak and dying is what evolution is all about, too. Nature rewards the strong and weeds out the weak.

Once or twice a day we passed clearings containing river villages consisting of a few thatched huts, without walls, on stilts, set just above the muddy water’s edge. These fascinated me. If we passed close enough, we could see people inside going about their business, much the way we in New York can look into apartment 12D across the street. What was it like to live so close to Nature, with the absence of walls only the most obvious sign of total subjugation to her whims?

Before I signed up for the trip, when I was still just toying with the idea of going to the jungle, I read an excerpt from Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? In it, Diamond describes how primitive nomadic tribes in places like New Guinea still routinely leave behind the sick and aged, simply moving on, without shedding tears, immune to the lonely deaths their loved ones will face.

Shedding the weak and dying is what evolution is all about, too. Nature rewards the strong and weeds out the weak. I wondered how my son, asthmatic as a boy, would have fared, or how long my mother would have lasted without the life-saving heart surgery of a few years ago. I doubt if I could have walked away from them, even if it meant harm to the community. And yet when I think about my own last days, I can only imagine begging my children to go on their way, to remember me as strong, and not to stand by and witness death up close.

Family Life: Brutish or Tranquil?

At a village called Puerto Miguel, I met and talked with a river family. Eugenia, 56, and her husband Manuel, 57, shared their walless house with her mother Dominga, 84, and the last of her seven kids, a teenaged son. The one-room house was divided into a kitchen and living area on one side and a sleeping area on the other where four small beds were crammed together, each covered by a mosquito net.

Both Eugenia and her mother had given birth to seven children at home, and neither had ever seen a doctor, let alone an OB-GYN. Whether each child got vaccinated or not depended on the Peruvian government investing in visiting nurses to visit poor villages that year.

A skiff takes travelers on a sunset expedition.

Though both women were missing teeth (no dentists), their skin was unlined and their hair jet-black. Dominga, who is illiterate, was walking in the village years ago when she heard a woman cry out in pain. She went into the house, and seeing the woman was in labor, took control and delivered the baby. “It was a miracle,” she said—one that made her realize she had the skills to be a midwife.

Dominga’s vigor and natural talents notwithstanding, Amazonian women’s lives seem nasty and brutish; their society is patriarchal. An enduring forest myth is that menstruating or pregnant women will take away a hunter’s powers.

But Manuel sat meekly beside his wife and mother in law, cutting plastic two-liter Inca Cola bottles into long strips that he planned to use to create fencing for his small patch of crops outside. Eugenia joked that Manuel had taken to drinking jungle elixirs made of bark and honey—with, I would later learn at a medicinal market, the occasional monkey penis tossed in for extra effect—to retain his sexual prowess, whereas she hadn’t noticed any ill effects of her own aging.

In the absence of basic medical care, I had no idea how Dominga could live so long and look so alert and healthy. Our guides credited the all-organic diet. The riverine people live from cradle to grave on freshly caught then salted fish, subsistence crops they grow themselves, and wild jungle fruits.

Submission to Nature’s Whims

The porousness of Miguel and Dominga’s house—no walls, let alone doors—suggested a comfort level with nature, and with the human community, that is completely alien to any city dweller or, for that matter, most Americans. When I asked what she worried about in the middle of the night, given that they slept in the open, in the middle of a jungle teeming with snakes and other predators—not to mention fellow villagers—Eugenia looked perplexed. She shrugged. “Tranquillo,” she finally said, using the Spanish word for calm. For her, the hormone-induced insomnia that has been plaguing me for years was apparently a foreign concept.

In the jungle, and on its edges, there is no denying the frailty, if not futility, of human intervention in the face of disease and death.

Despite the appeal of organic foods and sound sleep, I could never go thoroughly Rousseau and start idealizing the lives of the jungle people. The defining characteristic of their lives is animal submission to Nature’s whims. In the jungle, and on its edges, there is no denying the frailty, if not futility, of human intervention in the face of disease and death.

Days on the boat settled into a routine. Rise at dawn, ride in the skiff, return for breakfast, hike or skiff, then eat lunch and take a and nap. The mid-afternoon heat combined with the shush-shush-slap rhythm of the water against the hull, was almost coma inducing. My eyelids fluttered down, even while my body remained upright. In my air-conditioned cabin, I felt pinned to the bed, rendered supine by heat and idleness. Oh how I wish I could have bottled that sensation for my return to the city.

With my head on the pillow, my eyelids fluttering open and shut, the banks of the Amazon passed skittered by outside the window, as if in an old silent movie or a dream. In the land of mirrors, water became sky and the sky, waters.

Into the Dark

Late one afternoon, we set off on one of the black water tributaries for some caiman spotting. A warm, light rain fell. Armed with flashlights, we headed out in the forest to the shallow flooded areas, where the caiman lie in wait.

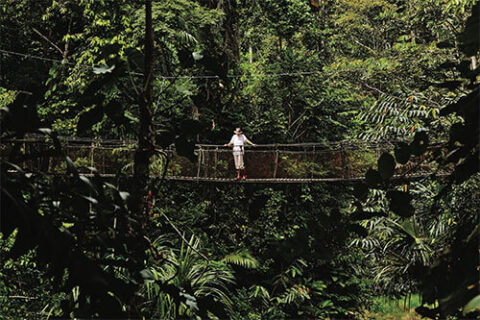

Nina on a bridge deep in the jungle. Photo credit: Adrian Gaut

Twilight lasts but a few moments near the equator. Billions of insects hissed, buzzed, sawed, broken only by the last coos and twitters of birds headed to their perches. At full darkness, we turned on the flashlights and aimed them at tangled roots and water lilies, seeking the telltale golden glint of the caiman’s reptile eyes reflecting the light. We saw a number of them, their log-like heads utterly still, waiting for the unsuspecting mammal or fish to come within range of their jaws. Our flashlights also picked up the reflection of a pair of golden eyes standing sentinel atop a dead tree— an owl, its darting eyes reflecting our beam like a pair of tiny searchlights.

Beneath us, the black water sighed against the metal bottom of the skiff. We lowered our waterproof flashlight under the surface, illuminating the eerie night world of sigh and grasses undulating around tree roots.

Suddenly a massive white orb appeared behind the scrim of green—the full moon. As we travelled onward, the moon flitted from on one side to the other of the narrow waterway, as the water meandered east and west. I was never more mystified at how the guides, without GPS, found their way out of these green water-mazes.

The Greeks spoke of the passage into death as a ride on a boat into an underworld where the dead would drink the waters of the river Lethe and forget their earthly life. I might wish that my own transition from life to death would feel like that ethereal moment on a tributary of the Amazon: painless, hallucinatory, ecstatic.

The Hour of the Wolf

Now back in New York, I know I only skirted the edge of that secret place. I saw enough to understand how muddy and forbidding it is, how man and beast alike within it submit to the rule that we are born and will die without leaving a trace. No dead animals last on the jungle floor, David Grann writes in The Lost City of Z. Insects and carrion birds transform the dead into something alive again within hours.

Insects and carrion birds transform the dead into something alive again within hours.

Birth, life, death, oblivion, and birth again—that’s the jungle. What if I had gone in deeper, or been born there? Would I have been one of the lucky thrivers, or among the left-behind? Would I have been pregnant at 14, mother to seven and toothless by 40, and sleeping through the night at 50, utterly tranquillo? Perhaps, like Eugenia, I would dream peacefully in the hour of the wolf rather than spend it wrestling to accept the fact that I am from the earth and to the earth I will return. Because in the jungle, the sweeter part of submission is the solace of witnessing how every death feeds a new, green life.

I only know there is a deeper place in the forest than any I have yet seen. I don’t want to go there until I absolutely must. But it frightens me a little less now.

A version of this article was originally published on NextTribe in September, 2017.

0 Comments