Rarely does a week go by that someone of my ilk—libtard lady of a certain age unhinged by news of the latest exploding cigar that the Insane Clown Posse in D.C. has stuffed into the tailpipe of our democracy—does not ask me, brows drooping with despair, “What would Molly say?”

That panicked question has haunted us ever since Molly’s death—too soon at age 62—a dozen years ago. Here with some much-needed reminders of what the woman herself not only would have, but did say, and say with more wit, incision, and passion than anyone else, we have award-winning director Janice Engel’s timely documentary, Raise Hell: The Life & Times of Molly Ivins.

Through an artful selection of archival video clips and interviews with friends and colleagues, Engel introduces Molly to those born too late to know the woman who—decades before Colbert, Samantha Bee, and Trevor Noah—was helping us make the poison pill of news go down with a spoonful of comedy sugar. Except that Molly was doing it without a team of writers. Or a security staff, for that matter, even in the face of death threats. And she was doing it while cranking out bestselling books, writing syndicated columns devoured by the readers of 400 newspapers across the country, and speaking anywhere a civil right was threatened, especially freedom of speech. And, unlike virtually every man of her stature, she was doing it without a handy helpmate making sure she ate right, had clean clothes, went to the doctor, and was fortified every night with love and support after a day of slaying dragons.

Molly Escapes

In Engel’s meticulously researched film, the uninitiated meet a girl born into privileged Houston family ruled by a hard-charging, heavy-drinking oil exec father. In Molly’s swanky River Oaks neighborhood, girdles and white gloves were the rule, and if a girl came out, it had damn well better be as a debutante. Good girls were expected to be cute and to be quiet. Molly’s big body—six-feet tall by the age of 12—precluded cute from an early age. And her big bookworm brain made quiet impossible and fiery clashes with her conservative father inevitable.

Raise Hell follows Molly as she escapes River Oaks and flees into journalism. After attending Smith, Columbia, and the Sorbonne, she earned her reporter’s stripes at newspapers around the country, including the New York Times. Twice a Pulitzer finalist, a champion of the underdog and a scourge of the powerful, Molly was also a talk show guest who cracked up the likes of David Letterman, Bryant Gumbel, and Conan O’Brien.

If the woman ever uttered a bite of sound that wasn’t funny, there’s no evidence in Engel’s artful compilation of clips. We have Molly coining the oft-plagiarized slam of right-wing rants, “It sounded better in the original German” and warning that if a certain dim-witted state rep’s IQ slipped any lower, “we’ll have to water him twice a day like a plant.”

To the initiated, those of us who came of age with Molly and followed gratefully along the thrilling new trails she blazed, the film is an opportunity to count again the ways we love our once and future queen. Just as Molly does in the documentary, I abandon any claim to objectivity. If ever anyone was genetically predestined to be an Ivins Acolyte, it was me.

The daughter of an Air Force officer born into the yessir/nosir world of begloved and begirdled good girls, I, too, was a shy bookworm who had mushroomed to nearly Molly’s height of six feet by the age of 12. I had no idea how badly I needed Molly until an unwanted move to Texas introduced me to my guru.

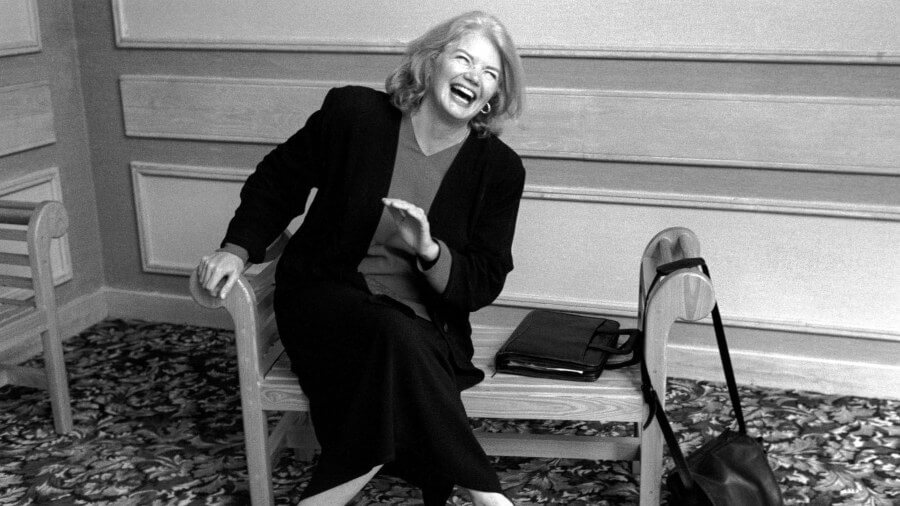

Molly Ivins at the New York Times in RAISE HELL: THE LIFE & TIMES OF MOLLY IVINS, a Magnolia Pictures release. © Molly Ivins Collection, Briscoe Archives. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Lesson One: Molly showed me how to be a woman in Texas. (Or a woman in any male-dominated fiefdom.)

I was a highly reluctant transplant when good love gone bad and a fellowship to study—you guessed it—journalism marooned me in Austin, Texas. This was 1973, and, though Austin was a rebel stronghold of cosmic cowboys and commie peaceniks, Texas still reminded me uncomfortably of the testosterone temples I had grown up around and left behind when my father retired and we moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico. There, in a state where Chapstick was a full make-up kit and no one burned a bra because they’d never owned one to begin with, I could finally breathe easy.

The Lone Star State’s hard-right politics and sky-high hairdos, on the other hand, were suffocating. I was on the verge of fleeing the state’s carnival of misogyny and racism when I discovered Molly. There, in the pages of the liberal beacon The Texas Observer, I found her practicing her belief that “Satire is the weapon of the powerless against the powerful.”

First Molly, and then her friend, future governor Ann Richards, showed me that a woman could be as big and big-mouthed as she liked, just as long as she got a good laugh and her facts straight. Molly taught me the way to a Texan’s heart is through the funny bone and the best humor amounts to truth delivered fast. She inspired me to write any number of slurs, slanders, and calumnies about the Great State and her citizens and to duck the punches with a well-placed punch line.

So I revered Molly early on. But like armadillo chili or chicken fried steaks the size of hubcaps, I assumed that she was a regional delicacy that didn’t travel well.

In 1991, I was soundly disabused of that notion. I was touring with my fourth novel, Virgin of the Rodeo, and had the misfortune of arriving in bookstores right after she’d appeared with her breakout bestseller, Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She? That was when I learned the hard way this basic rule about public speaking: Never Follow Molly Ivins. I was tall andI was, sort of, a Texan, but lord God awmighty, did disappointed readers from Seattle to Manhattan ever let me know that I was no Molly Ivins.

Read More: The Tiny Pricks Project: Protesting Misogyny One Stitch at a Time

Lesson Two: Molly Showed Me How to Live Boldly

Molly was always and unashamedly Molly. If that meant bringing a dog named Shit and her own bare feet into the NY Times newsroom, well, deal with it. She wasn’t going to shod herself or shoo Shit for anyone.

If being Molly meant sticking a cowboy hat on her head, driving a truck, and dragging her Smith/Sorbonne accent out into the most redneck of drawls, so be it. Like innumerable men before her, she discovered what a giant free pass the label “Texan” was. Instead of an uppity, loud-mouthed, liberal lady, she was a “Texan.” And everyone knew that Texans were genetically doomed to be bigger-than-life, bombastic mavericks. Long before the concept was applied to anything other than cattle, Molly understood branding and used it brilliantly to make her truth heard in a world that tended to tune out female frequencies. Molly made sure that no one could ever dismiss her as “shrill.”

Molly did fearless even better than she did funny. In spite of hate mail and attacks by the likes of Rush Limbaugh—an experience she likened to being gummed by a newt—she went right on saying that this president was “weak as bus station chili” or that another’s vice president was “dumber than advertised.” She did fearless so well, in fact, that a person could have been forgiven for believing that life came easy to her. That she was the rare woman immune to the insecurities and anxieties that make the rest of us especially prone to doubting ourselves.

A person with such immunity, however, wouldn’t have written a note like the one Molly penned to herself on August 30, 1973, the day she turned 29. Contemplating the endless hours she spent at Scholz Garten, an Austin watering hole beloved by 70’s liberal politicos and the journalists pumping them for stories, Molly wrote that she “Came very close to becoming an alcoholic. Probably am one. … But, God, I do enjoy having a crowd.”

After using alcohol as an anesthetic for most of her life, Molly, with the help of some of her closest friends in that crowd, checked herself into “drunk school” and came to terms with her alcoholism.

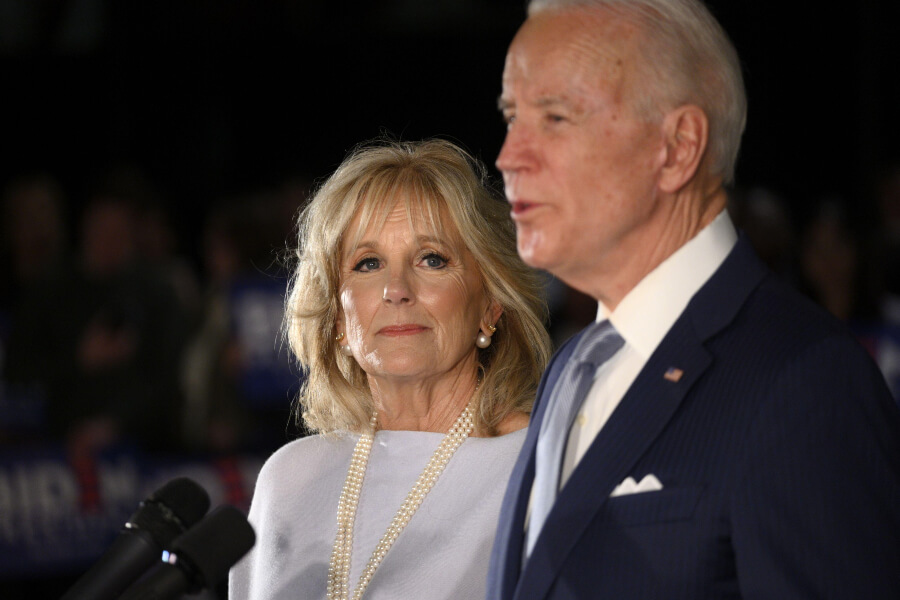

Molly Ivins in RAISE HELL: THE LIFE & TIMES OF MOLLY IVINS, a Magnolia Pictures release. © Melanie West. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Lesson Three: Molly Shows Me How to Die Boldly

Even more inspiring than how she showed us all a singular way to live boldly, was how she modeled a fearless, forthright, and funny way to approach the end. “Having cancer is massive amounts of no fun,” she wrote in 1999 after being diagnosed with breast cancer. “First they mutilate you; then they poison you; then they burn you. I have been on blind dates better than that.”

The last time I saw Molly, shortly before her death in 2006, she was speaking at a fundraiser for crusading investigative journalists. She took the podium and stood before us, a vision of courage, gloriously, unapologetically, un-bewigged or turbaned, brilliantly bald beneath the glare of an overhead light. She called us “beloveds” and gave us the forever answer to our question of what Molly would say. No matter what new depths of dumbassery our politicians might descend to, Molly ordered us, “Y’all, keep on raising hell.”

Then, grinning a grin that shone bright as a full moon beaming in a midnight dark sky, Molly added, “And have fun doing it.”

Read More: How to Raise Sons Who Won’t Turn Out Like Harvey Weinstein

0 Comments