Megan Conway remembers the dramatic moment when, at 17, she became an activist. It was her senior year at the large, upscale Lowell High, in San Francisco. Conway, now 49, was leading a group of fellow students with disabilities into the gym to register for classes. Born deafblind, she was wearing her thick glasses and hearing aid and walking into the huge space, followed by about 15 other students, some with obvious signs of disability (wheelchairs, canes, or visible markers of Downs Syndrome). They’d been given permission to register before the other students: a necessity, given the chaos of fast-footed students racing to nab their favorite courses in the crowded area.

Suddenly Conway was blocked by a tall, angry male preppy. “Hey! Where are you going?” the boy demanded.

“We’re the students with disabilities,” Conway answered. “We were told we could register first.”

“Oh, no you don’t!” shouted the boy. “We honors students are registering first!”

“That moment was life altering,” Conway says.” I realized I had to fight back.” She looked at the kids behind her and “got really mad on their behalf!” She told the rude, path-blocking boy: “Why does being in the honors society make you worthy when having a disability doesn’t?’ I realized that people were looking at those of us with disabilities as ‘privileged.’ But being able to sign up for classes first was a necessity—a way of surviving in school.”

The bully activated what would become a lifelong passion. “I complained to the principal, and I wrote an opinion piece for the school newspaper.” Working for disability rights would be Conway’s calling and informing all that she does is an insistence that disability is “not a ‘deficit’ issue but, rather, a—positive—’diversity’ issue.” Especially in light of new proposals from the Trump Administration and dire budget cuts for people with disabilities, it feels particularly important to hear her story now.

The Heart of an Activist

Megan and her dog Penina on Kailua Beach.

Megan Conway, who lives in Hawaii with her husband, Tom, their 14-year-old daughter, Susanna, and her “gorgeous” hearing dog, Penina, is one of 70,000 Americans who are born deafblind (that’s the way it’s said now, as one word): She’s severely hard of hearing and legally blind, with 20/200 vision. She struggled gamely through school, and after her awakening as an activist, she went on to face enormous challenges to earn her PhD in special education. Today she is a specialist at the Center on Disability Studies at the University of Hawaii.

Recently I spoke to her on the phone, which in and of itself is a miracle. “I’m talking to you using a Bluetooth that goes to an assistive-listening device that’s sending the sounds to my hearing aid, which is amplifying the sound so I can hear it,” she explained. “I depend so much on technology to communicate.”

[My dog] tells me about the phone, the smoke alarm, the kitchen timer, the doorbell.

Her indispensable dog Penina also helps her “hear”—Conway explains one of the “cool” things she does for her. “If I’m walking along and I drop my keys, I don’t hear them fall,” Penina will nudge her. “She then takes me back to the keys, and then I give her a command and she picks up the keys and gives them to me. She alerts me to sound with a nudge. I will say, `What?’ in sign language and in voice. She tells me about the phone, the smoke alarm, the kitchen timer, the doorbell.” Both the technology and the service dogs are desperately needed by the deafblind community, and one of the missions of Deafblind Citizens in Action (DCBA), on whose board Conway sits, is to increase funding for the community.

Read More: The Secret Tragedy of Native American Health—& What One Amazing Woman Is Doing about It

A Mother’s Gift

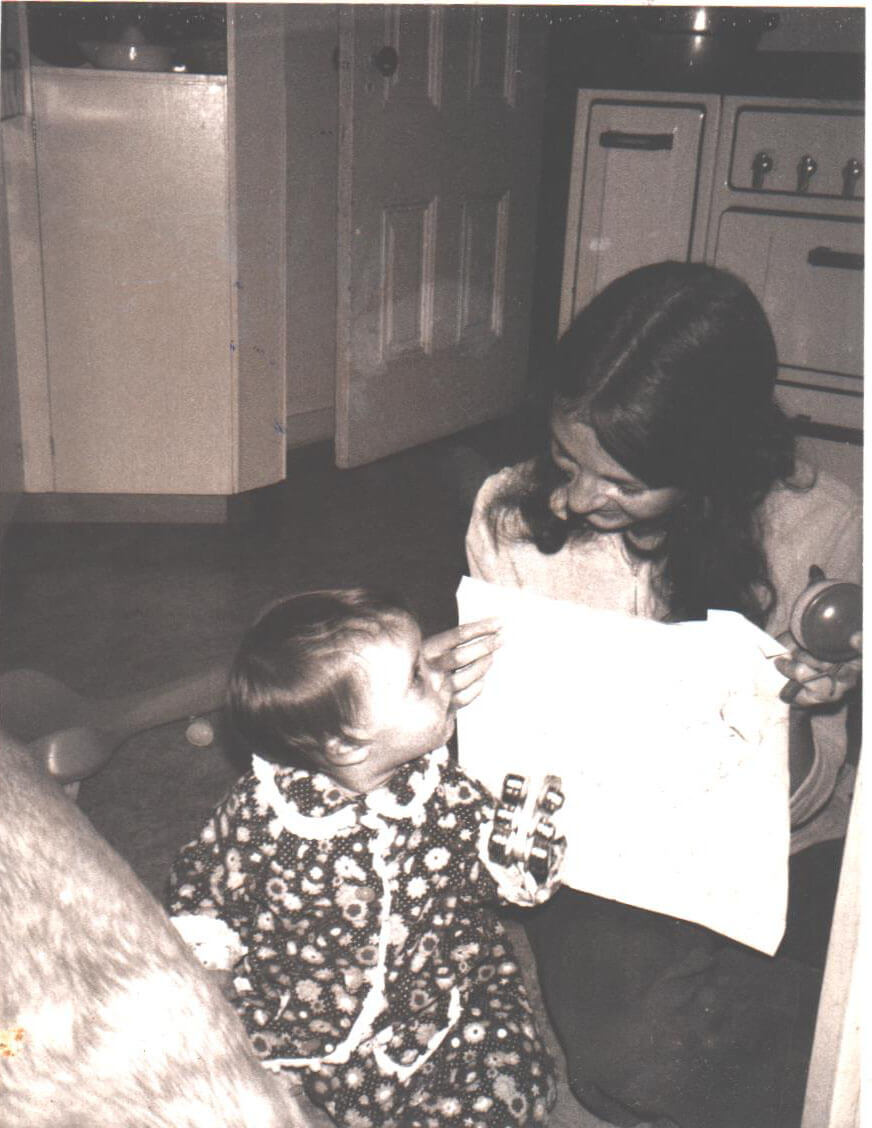

Megan and her mother Pamela when Megan was in nursery school.

Conway was raised in San Francisco as the sole child of a single mother, Pamela Jones; it was her and her “awesome” mom against the world. Pamela, though well educated, juggled part-time work—as a teacher’s aide, a receptionist, “even cleaning hotels for a while: always figuring a way to survive”—to support her daughter. “It was a different time—you could live on less,” she says of the Bay Area of almost a half century ago, its Haight Ashbury anti-materialistic idealism still wafting in an air that’s now super-charged with Silicon Valley mega-wealth. “So we never starved to death, and I had a very stable, supported life because of my mother, even though we were hand to mouth my whole childhood.”

When Conway was four, she spent a day in the care of her father, whom her mother had divorced and who was not extremely attentive. Her father and his girlfriend left Conway and the girlfriend’s son to play with shopping carts outside of a grocery store, and Conway was hit in the face with a fast-careening metal cart. “My eye was bleeding! I went into shock!” she recalls. She had a very thin cornea to begin with; by the time she was treated, she’d lost all vision in her left eye.

The year Conway started kindergarten—1975—was the year that what was then called the All Handicapped Children’s Act was passed. Today it’s called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and the earlier, more judgmental name jibed with the way that kids like Conway were treated. At the local kindergarten “they wanted to put me in the basement, all by myself. I would have my own teacher there. My mother said: ‘No way!’ It wasn’t that she didn’t want me to have the support” of a specially trained teacher. “She just didn’t want me to be all alone.” Such isolation was certain to invite stigmatization.

Conway didn’t get the support that she needed from her year of mainstream kindergarten. So her mother pushed for the school district to pay for Conway to attend the small Montessori school: a better choice. “I wore hearing aids and large, heavy glasses,” and, given the need to keep those glasses from falling down, “I’m probably the only person in the world who is sorry to have a small nose.

Yet it wasn’t so much how she looked that made relating difficult; it was her inability to pick up social cues. “I didn’t hear kids when they said hello to me. (I still have this problem as an adult.) They expect, when you encounter them, for you to smile and make eye contact, but I didn’t know if they were making eye contact with me. So people think you’re weird.” As an adult, especially with Penina, it’s easier to find those unseen signals. But as a junior high school student, “the kids would imitate me” in a ridiculing way: “standing real close to the blackboard to see it and things like that. I got a lot of bullying.”

Still, perhaps because of the self-esteem she gleaned through her mother and perhaps from a need to survive, “the teasing didn’t make me feel bad about myself. Instead, it made me feel like, `Who the hell are you to rat me out like that? I’m not a bad person!’ It felt unfair, and I didn’t know why it was happening.” Conway’s mother had friends, many of them other single mothers, with daughters without disabilities. These girls befriended Conway and in that small community—the mom-girl duos cosseted and wisened-up by their shared challenges—Conway was protected from ridicule that could otherwise have been horrendous.

The teasing didn’t make me feel bad about myself. … It felt unfair.

But in her early teen years “I became more aware” of being picked on. “I didn’t have many friends. I had a lot of difficulty with the teasing at school. I grappled with my disability and spent a period of time feeling sorry for myself.” She missed a lot in her classes. “I would get a test back, and even though I knew the material, I hadn’t been able to hear the teacher talk about it in class.” That lack of opportunity showed in the grades she received on the tests.

Resources for disabled kids in high schools at the time weren’t great, but Conway was saved by the fact that her school finally acquired a rehabilitative counselor and a roving teacher to come intermittently for the few disabled students. The roving teacher taught Conway Braille, something she had never had to learn because she’d been able to read, with difficulty, enlarged-print type. (Her part-visibility, ironically, made learning Braille late a bit challenging.) Both educators convinced school authorities to let Conway have more time completing her tests than her nondisabled classmates.

Learning to Fly

Megan in 1st grade.

Following Conway’s high-school transformation into an activist, she started working at a summer camp for blind kids and met her first boyfriend, a fellow counselor, there. Interestingly, neither he nor none of her subsequent boyfriends had a disability (nor does her husband). “They were all pretty compassionate guys,” she says, “who seemed to understand that dating was difficult for me. There’s a whole social thing that goes on with flirting, where you have to be subtle in conversation, and I could never get it down. So I just learned to be like”—she laughs as she exaggerates—”‘Want to go into the woods and make out?’ Not all guys can take that bluntness, but a few did. And you can build from there.”

Conway entered college at the University of California at Berkeley, in 1989. There she experienced an intense sense of community with other disabled students at the famously political school. “We students with disabilities on campus had such a common political agenda. One of my best friends had orthopedic disabilities, and we just always understood each other,” she says. Still—even at a school as progressive as Berkeley—she had difficulty getting the special academic resources she sorely required. This gap sharpened and refined her goal of advocating for the disabled.

Pursuing her Special Ed PhD Conway was the only candidate with a disability—much less two. “I had a couple of really fabulous professors, who became my advisors, but a lot of the other professors and people at the disability support office looked at me like, ‘Whoaa! …'” She believes they feared she was going to ask for more support than was convenient for them to give.

Pursuing her PhD, Conway was the only candidate with a disability—much less two.

It was true: “I needed more ‘people support’; I needed a human to read through my papers.” As a deafblind person, even with some helpful technology (remember: the advanced, helpful technology was not invented yet), “it takes me three or four times as long to read something as it takes anybody else. I needed somebody to help take notes for me in class.”

But the people running the PhD program didn’t want to pay for a competent helper. “They said, `You can have a volunteer. Or you can have somebody for six dollars an hour.’” A volunteer or a helper at that pay grade simply wasn’t sophisticated enough. Her mom stepped in again, assisting Conway for much of her PhD program. “It’s real fun having your mom come to class with you when you’re 23.” Conway also paid some smart friends out of her own pocket.

During the process of getting her PhD, Conway stretched her capabilities by traveling internationally alone. Working for a deafblind charity called Sense—which helps deafblind people improve their technology—she spent time in the U.K. “I would go up to Glasgow for a weekend! I got on the train by myself!” She used a cane “and it let people know that I needed help maneuvering.” The experience of getting around by herself in a foreign country “gave me a lot of confidence—’I can do this!'”

Read More: The Incredible Life of Congresswoman Jackie Speier

Earning Her Way

Megan Conway and her daughter Susanna.

Upon earning her PhD, Conway wanted to work as a college faculty member in special education. On her applications she was upfront about her disability. She was proud of who she was. “But, in hindsight, maybe I shouldn’t have” been so forthright, she says. “That’s the problem with being confident—I didn’t properly imagine how being honest would have negative consequences.”

Conway thought she’d be an attractive hire. She had published papers. She had presented, traveled, and consulted internationally. But it was not so easy. Even in the field of disability rights, “When people see you’re deafblind, they immediately have an image of somebody who needs a lot of support.” Conway ended up being hired by the University of Hawaii through a Berkeley mentor who had a disability. It took a village—and it is a village she still belongs to. “When I get a resume from someone with a disability, I pay attention. You have empathy with people who share your situation. But it’s very important to have connections with people with and without disabilities—that’s how networking works.”

Our daughter says: ‘Mom’s the president, dad’s the mayor, and I’m the citizen.’

Moving to Hawaii in 2001 was both a challenge—there was more shame around disability there and a less cohesive community—and joy. “It’s not hard to love. It’s a warm and unique place.” And it got even better when she met a caring man, Tom Conway, also a faculty member at the Center for Disability Studies, soon after she arrived.” They married a year later. Conway says she married a man without disabilities “just by happenstance. It wasn’t on purpose!”

She and Tom have a “very typical marriage,” she says, adding, wryly: “I’m the boss. Our daughter says: `Mom’s the president, dad’s the mayor, and I’m the citizen.’ But I don’t drive and my husband definitely has some additional responsibilities. But, other than that, it’s like any other marriage, including a couple of rough patches where we saw a counselor about male communication versus female communication—that kind of thing.”

Activist in Action

Megan with husband Tom and daughter Susanna near the Golden Gate Bridge during a holiday visit to the Bay Area.

Conway’s mission, in her teaching and in her work on the board of directors of DBCA, is to help deafblind people set their own agenda, including teaching leadership skills. Every year she brings a group of young deafblind people to Washington D.C. to lobby for funds and to help the kids “flex their muscles.”

And help them flex their muscles she does. Sajja Koirala is a blind student of Conway’s, going for her PhD in sociology. “I had a rough time last semester with the workload,” Koirala says, “and Dr. Conway shared with me that she had hired an assistant as soon as she started her doctorate. She suggested I do the same.” That made the difference. “She is so real. She is not afraid to speak of her vulnerability. She does not lecture you about how ‘nothing is impossible.’ She openly admits her limitations, and she will sympathetically listen to someone if they speak of their own. She is funny, proud, and easy-going.”

She does not lecture you about how ‘nothing is impossible.’ She openly admits her limitations.

Koirala tells of trying to meet Conway for lunch one day, but they couldn’t find each other. “I called her on her cell, and it turned out that she was also looking for me. She asked me if I am sitting or standing, and goes on to say, ‘Okay, blind looking for the blind. I will find you!’”

Now the task is to not only help make young people with disabilities equally proud, comfortable, and competent—but to make the non-disabled world understand how essential and fair and decent it is to let the deafblind and all disabled Americans have the resources they need to live full lives.

Having gotten to know Megan Conway, I believe she can do that.

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

0 Comments