Over the past months, we’ve been inundated with entries in our second short story contest. Our judges had a difficult task for sure, but they picked this “moving” story about losing a child by Lisa Robertson as a runner-up. Stay tuned to read another runner-up and the winning short story in the next two days.

***

Peach

Here’s the thing about becoming a ghost—there is no onboarding process. No orientation day. No dead girl handbook. Nothing like that. In movies and books, they always talk about being enveloped in a bright light, feeling an overwhelming sense of peace, and being welcomed by all your loved ones that went before you.

For me? Not so much. Somehow, I’ve ended up back in my childhood home, watching my previously perfect mother drink until she passes out each night. Apparently, that’s my eternity. Pardon me for being a little pissed about it.

If there are rules and regulations on ghost behavior, I sure can’t figure them out. I always assumed that ghosts were anchored to the place where they died, but now I think we’re actually tied to the people we loved the most or who loved us the most. That’s why I’m stuck with Mom.

It’s like we always said: I was her person, and she was mine.

It’s like we always said: I was her person, and she was mine.

The weird thing is that when I think about other people I love, a lot of times I wind up being in their presence. Not every time, but more than you’d think. My cousin was born a month after I went away. They named her Georgia after me. Sometimes, when she’s fussy, I linger over her crib and sing to her. When my grandpa got sick, I sat with him in the hospital. He asked, “Is that you, Peach?” He’s practically deaf, so I couldn’t make him hear me. I just patted his leg. And when my grandma came back in the room, he told her I had been there. I squeezed her hand as she cried. So, even if they aren’t sure, people do get that distinctly “Peach-y” vibe when I’m around. I mean, my dog practically shits himself when I rub his belly. Every. Single. Time.

But not my mom. She can’t feel me. I’ve tried yelling at her—that doesn’t work. Sometimes I move things, but she’s too distracted to notice. She was always so organized before. A place for everything, everything in its place—she even alphabetized the spice rack. God help you if you put the cinnamon before the cardamom. But now? Now, there are days when she forgets to brush her hair. She went to Kroger with her sweat pants on inside out last week. People she’s known for years don’t recognize her anymore.

Maybe they just pretend not to. It’s hard to say.

Ellie

When your kid disappears, initially people cut you a lot of slack. In the first two days alone, my neighbors brought over three platters of lasagna, two jumbo buckets of fried chicken, and a vat of chili. Don’t even get me started on all the cobblers. The HOA’s social committee must have bought every flat of blackberries in town. It’s kind, but it’s also kind of overwhelming.

But as things drag on and your circle gets smaller and smaller, so do the acts of kindness. People don’t know what to say, so they don’t say anything. A little time passes, and now it’s like your tragedy is contagious and you’re more isolated than a floor of COVID patients in March 2020.

If there is one thing that people of all religions, political affiliations, gender identities, and sexual preferences can agree on, it’s that they don’t want to spend a whole lot of time with the mom of a missing girl.

People keep telling me that she’s communicating with them.

They do want to share all their stories, though. And I understand why. When they remember something about Peach, they want to tell the one person they know is still obsessed with her, and that’s me. They want me to know that she was important to them, that she touched their lives. And I’m grateful for that, even when it’s hard to hear.

But now people keep telling me that she’s communicating with them. I hear these stories from everyone: my parents, Peach’s friends. Just last night, my niece swore she heard her singing over the baby monitor—like Peach was serenading her newborn.

Don’t they get it? If Peach is reaching out to them, that means Peach is dead. Why is that so easy for them to accept? And why are they so convinced that she would contact them? If Peach was able to communicate, she would communicate with me . . . not her high school boyfriend, not an infant, not some random coworker who saw her in a dream. Me. Peach would talk to me.

Peach

I’m not sure how long I’ve been dead. Well, officially, I’m not dead. I’m missing. But everybody knows I’m dead. Everybody knows it, but nobody says it out loud—everybody except my mom.

She zones out on the couch watching awful reality shows all day, then sleeps in my bed at night. She is completely rudderless—baking loaf after loaf of soda bread no one ever eats because I used to bug her to make it all the time.

Everybody knows I’m dead. Everybody except my mom.

Then there’s the good china. She was so proud of it before. We ate grilled cheese and Oreos on it when I got a perfect attendance award in the second grade, clinking crystal champagne flutes filled with fizzy white grape juice to toast my achievement.

But yesterday, she took it out of the cupboard and broke all of it—12 five-piece place settings, the sugar bowl, the gravy boat—every last bit of it, one by one, slamming each piece on the tile floor while shards scattered all around her. Mom was always the most normal person in any room, but this has made her certifiable.

Ellie

I’m sitting in my boss’s office, trying not to stare at the crumbs nestled in his bushy mustache. He’s there with some woman from HR. She keeps pushing a box of Kleenex at me even though I’m not crying. “We’ve been as patient as we can be, Ellie. But your job performance—all the mistakes, the missed deadlines . . .” His voice trails off.

“We aren’t unsympathetic to your situation,” the HR lady chimes in. “But it isn’t fair to your coworkers that they still have to pick up your slack. If you are going to be here, you have to be here. And at the level you were before.”

“It’s not just that,” my boss says. He looks like he’s about to cry. And I remember how he and his wife sat in my living room in those first few days. She cleaned my kitchen. He mowed my yard and ran interference with the reporters. “We love you, Ellie. We want you to get better.”

It’s always the same. People are concerned. They’ve run out of patience. They want me to be who I used to be.

The HR lady squares her shoulders. “It’s been six months. If we don’t see immediate improvement, we will have to terminate your employment. We’ve drafted this 30-day Performance Improvement Plan. You need to follow it if you want to keep your job.” She slides some forms at me, blanks conveniently highlighted for my initials.

I stare, first at the paperwork, then at them. There was a time—not that long ago—when a makeshift intervention like this would have scared the shit out of me. But I’ve had similar come-to-Jesus meetings with my friends, my family, even myself.

It’s always the same. They’re concerned. They’ve run out of patience. They want me to be who I used to be. Look, I don’t know if Peach is dead or not, but the person I used to be—she is dead. And she won’t be coming back.

I sign the paperwork, leave it on his desk, and head home.

Peach

It was rainy the night I died. Windy, too. The drops came down like pellets—hard, relentless, cold. The news said the cops found my car with the door wide open, my takeout and backpack sitting on the passenger seat, rain puddling on the floorboard.

I don’t remember everything, just a few things here and there. Dodging a shopping cart that blew across the strip mall’s parking lot. Pulling my hair into a sloppy, wet bun while waiting for the heater to kick in. And the eyes of the man that killed me. I remember those, too.

It was Mr. Schultz, my history professor. To us, he was Professor Call Me Doug because that’s what he always said . . . call me Doug. I needed an upper-level history class to graduate, and the only opening was in Call Me Doug’s Tuesday night course on the Habsburg Monarchy and all their inbred glory. Katie, my sorority sister, was stuck in the class too—she said Call Me Doug was a “hot nerd.” To me, he was just . . . weird. Not in a way you could object to, but in a way that made you feel uncomfortable and—I dunno—vulnerable, I guess.

Once he had me stay after class to discuss a paper I was working on. I mean, there was nothing to talk about, and he was flop sweating the whole time. Then he insisted on walking me to my car “for safety.” There was a moment while we stood by my car where I thought he was going to try to kiss me. But he didn’t, and I thought I must have imagined it.

He never did or said anything over the line, but he was always there, always watching.

I waited tables at a diner just a block off campus. I’d been working there a couple months when Call Me Doug first came in. After that, he came in most nights and always asked to sit in my section. He never did or said anything over the line, but he was always there, always watching.

I wish I had told my mom or my manager or my friends about Call Me Doug, but there wasn’t really anything to say. It’s not like he was doing something wrong. Plus, he was my professor. I didn’t want to get him in trouble or make him mad. Look, it’s not like a socially awkward guy hitting on you should be considered a breaking news story.

The second he approached my car that night, I knew it was him. It was his eyes—he was glaring at me through the holes in his ski mask. The fact that he was wearing a mask and a huge puffer jacket made me kind of hopeful at first. Like maybe he was wearing them so I couldn’t ID him—so he wouldn’t have to kill me. It was just the last and worst in a long line of bad assumptions I made about Professor Call Me Doug.

Ellie

I used to be surgically attached to my phone. Peach said I was more addicted to texting than she was. She wasn’t wrong. I ran my life from that thing. But now I can go all day without checking it. I don’t have much of a life to run anymore. So, I didn’t expect to hear the notification ping go off over and over again this morning.

When I grabbed it off the charger, I saw 13 text messages—they were all from an unknown number, each a string of peach and shovel emojis followed by a half dozen exclamation points. This has happened before: people taunting me with anonymous, cryptic, or cruel messages about Peach. About a week after she went missing, a six-page handwritten letter showed up in my mailbox. It said Peach hated me and that she chose to disappear to get away from me. Strangers on Facebook post that they know I killed her. Psychics offer to help find her if we pay them enough money. If there is one thing I’ve learned through all of this, it’s that there is no bottom for some people. I hit delete, blocked the number, and put the phone in a drawer.

I saw 13 text messages—they were all from an unknown number, each a string of peach and shovel emojis followed by a half dozen exclamation points.

I’ve been talking to Peach a lot lately, begging her to come home. Would knowing one way or the other make this any easier? I don’t know. I do know I’m the only one who still has any hope. And that’s a real lonely place to be. But late at night, when I lie in her bed, surrounded by all her things, I can’t come up with a single scenario where she could still be alive.

I hung her Christmas stocking on the mantle; made her favorite baked beans at Easter. But as these holidays and seasons pass, I know Peach is not coming back.

I know it. I can’t say it. But I know it. I miss her laugh. Her messy bathroom and endless laundry. Her melodramatics and goofiness. All of it. I miss all of it. I miss all of her. Why am I the one person she doesn’t want to talk to when I’m the one person who would gladly give my life for one more conversation?

Peach

I used to love watching those horrible basic cable shows with mediums who flubbed all the messages from beyond. Now I understand why they never got anything right. It is not easy for a dead person to send a message. And it’s sure not straightforward. It would be nice if I could just leave a note on the fridge, “Hey Mom, Doug Schultz killed me. My body is at the bottom of a stock pond on his parents’ farm. Don’t forget to buy dog food.”

But it doesn’t work like that. The best I could do was texting emojis of a peach and shovel. She isn’t going to get “Doug” out of something you dig with.

I know if I can convince Mom I’m dead, maybe she can move on.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this—I know if I can convince Mom I’m dead, maybe she can move on. Maybe I can, too. Every now and then I get glimpses of this really bright warm light that I want so much to walk into. But just as quick as the light shows up, it disappears again. Maybe it opens some kind of portal whenever Mom thinks I’m dead, and then goes dim when she tells herself not to think that way?

It feels like I’m still here because our souls are tangled together like a skein of yarn with 21 years’ worth of knots inside. There has to be some way to unravel them.

She’s laying down on the couch, eyes shut, but not asleep. I lean down next to her and hug her close. She rustles around a bit but doesn’t respond. I give her the same Eskimo kiss she’s given me a million times and whisper, “You have to let me go.”

Her eyes open and she looks in my direction. She can’t see me, but she knows I’m there. I know she does. “I can come with you.”

“This isn’t sleepaway camp, Mom. You can’t sneak in to check up on me—I have to do this alone, and so do you.”

“You’re my person, Peach.”

“You’re my person, Mom.”

The light swirls around me, and I’m floating first above my room, then my house, then my street. I can’t see Mom, but I can feel her. Just like I always have. Just like I always will. Because she is my person, and I am hers.

***

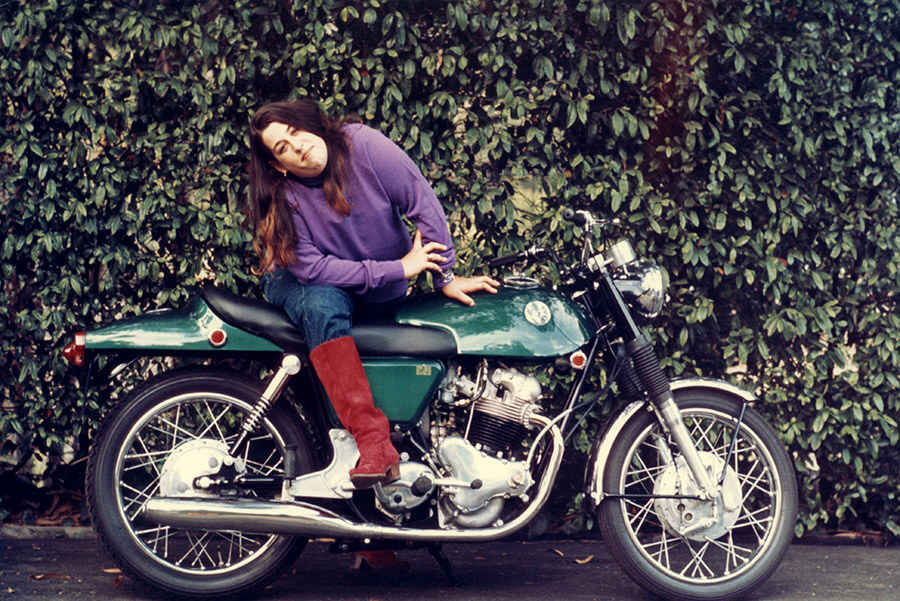

Lisa Robertson is a magazine editor and feature writer living and working in the DFW metroplex. This short story was inspired by the death of her daughter, McKenna, in 2020 and is her first fiction publication credit. When she’s not scratch baking or spoiling all the “littles” in her life, Lisa works on short stories and looks forward to the release of her debut novel,The Collector, later this year.

0 Comments