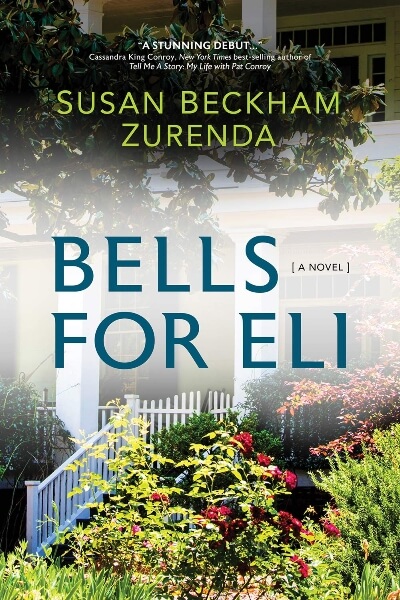

Family secrets too incendiary to see the light of day are a staple of Southern Literature. As an English teacher for 33 years, Susan Beckham Zurenda knows that well, and her debut novel, Bells for Eli, delivers a haunting coming-of-age narrative, a destroyed Southern childhood, forbidden love, and a tragic twist. Think of a Tennessee Williams story that takes place in the ’60s and ’70s.

Zurenda follows first cousins Ellison (Eli) Winfield and Adeline (Delia) Green, growing up in the fictional town of Green Branch, SC. Of course, there’s an antebellum house and a lineage that goes back to slave-holding days. The story is set in motion by a childhood accident that will impact the rest of Eli’s life. And Delia’s too, as she becomes his protector and more.

The characters are beautifully crafted and heartbreaking at times. The writing vividly evokes a fleeting time and place; I, having been raised in the South myself, could almost hear the crickets, see the fireflies, and taste the Moonpies as I read. The story stays with you, and reminds you that certain relationships exist on a whole other, almost magical, plane.

I was fortunate to be able to talk to Zurenda, who lives in Spartanburg, SC, about her wonderful, moving novel.

How did your career as an English teacher influence your writing?

Teaching literature has encouraged my own writing on many levels. I’ll mention a couple. First, is the inspiration. The fulfillment that reading good literature brings to me encouraged me to write about the human experience. Also, analyzing literature with students for so many years continually exposed me to the how and why of characters’ lives and conditions. There is no greater teacher for writing fiction than teaching fiction.

Helping students engage in literature for 33 years convinced me that there is no field of study any more important. It brings knowledge, satisfaction, wisdom, and engagement. Literature reveals truths about what it means to be human more than any other discipline. It forces us to see as others see, to feel as others feel, to connect others’ experience to ourselves and thereby achieve greater understanding (the good, the bad, and the ugly) of our own human nature.

What are your favorite authors and books?

Where do I start? Tennessee Williams, William Faulkner, Peter Taylor, Robert Penn Warren, Pat Conroy, James Agee, James Dickey, Kaye Gibbons, Ralph Ellison, Ernest Gaines, Reynolds Price, Walker Percy, Harper Lee, Zora Neale Hurston— to name a few. I taught works by all of these fine writers because of the tremendous impressions their stories create. They show us the truth of who we are.

But what started my love of Southern authors was an elective course I took in Southern Literature during the fall of my sophomore year in college. This class was an impetus that changed my direction from being a music major to an English major. We read the works of four writers, all mid-20th Century women: Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, and Katherine Anne Porter. Those writers became important influences on my love and appreciation of Southern Literature.

I’ve read The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald more times than any other book. One reason is I taught Fitzgerald’s classic many times, yet no department head or administrator ever told me I had to teach that book. Then why did I choose to teach it and to read it many times? So many aspects of the novel pull me in. The compact writing where every word counts. The powerful symbols. Fitzgerald’s understanding and compassion for Gatsby. How the story moves me in ways I don’t expect, no matter how many times I read it. Jay Gatsby breaks my heart.

The point of view in The Great Gatsby has always intrigued me as well because the protagonist, Nick Carroway, is not the main character. When I wrote Bells for Eli, I challenged myself to create a similar point of view. Eli is perhaps the dominant character in my novel, but Delia is the protagonist.

How long have you been working on this debut novel?

It took me about a year, writing three to four nights a week, to compose the original manuscript of Bells for Eli that my agent took. Later, I did a major revision and developed the important mystery and subplot surrounding Francie Turner. I invented the basics of Francie’s story on a long bike ride one afternoon. Creating this subplot brought everything in the novel together in a way I had not anticipated and gave me the ending I’d been struggling to achieve.

What inspired you to write the book?

Bells for Eli is inspired by an incident that actually happened to my first cousin Danny when he was very young, on his second birthday. His family was living in Plainfield, NJ, and my family was in South Carolina. As is the case in the novel with my character Ellison (Eli) Winfield, my cousin saw a Coca-Cola bottle sitting on the porch steps at his home and drank from it. Instead of Coke, though, the bottle was filled with Red Devil Lye, a chemical with properties like helium. My uncle had been placing balloons over the neck of the bottle to inflate them for his son’s birthday party. Like Eli in the novel, my cousin survived the accident, but his life was forever changed.

My purpose in Bells for Eli is to consider the irony of fate: how it can take with one hand and give with the other.

I did not grow up in the same town as my cousin, and most of what I know of his challenging childhood came to me secondhand long after my own childhood. My novel is primarily an imagining of Eli and Delia growing up across the street from each other in a small-town South Carolina neighborhood, as Delia becomes Eli’s defender and they develop a deep and uncommon love, as they come of age in the 1960’s, a powerfully transitional period of American history.

Is Green Branch based on any real town? How important is place in your story?

Green Branch is a fictitious town in South Carolina, but there are bits and pieces of this setting based on my hometown of Lancaster, SC, and my mother’s hometown of Winnsboro, SC. Also, I needed an all-male and all-female college in my plot, and at first I thought to send Delia and Eli to college in the Northeast because I had sent Eli to a boarding school in Connecticut. At some point in my process of researching colleges and universities, however, I realized I already had the perfect models for an all-male and all-female college in my head: Wofford College and my alma mater, Converse College in Spartanburg, SC. Thus, I decided to bring Eli home and enroll my characters in college in South Carolina.

Also, one of the settings in the novel where powerful scenes take place is Magnolia Manor, the home of Eli’s genteel grandmother. I based the home and its atmosphere on memories of my great-grandparents’ antebellum home on the outskirts of Lancaster, SC. An important object in the setting at Magnolia Manor is the old bell alarm tower in the backyard. The tower in the novel is based on a 70-foot tall structure on my great-grandparents’ property that I climbed many times during my childhood.

Place is essential in Bells for Eli. The circumstances could not take place in the same way anywhere else. Southern characters, like characters in many regions, are deeply affected by their setting and atmosphere. My characters act and respond as they do in part because of where they live.

Also, though not as true in the 21st Century, Southerners have tended to stay in their native locations. My characters’ families have lived in and around Green Branch for many generations. For my main characters and first cousins Eli Winfield and Delia Green, the meaning of home in the present is influenced by knowledge of their families’ past.

Partly because of an unspoken Southern understanding about alliances, after Eli’s tragic childhood accident, the cousins develop an unbreakable bond. They live across the street from each other, and though Eli’s mother is of landed aristocracy and Delia is the child of first generation college parents, social boundaries do not exist between them. My characters express both an adherence to and rebellion against traditions and mores particular to the small-town South of the Mid-twentieth Century.

What do you want readers to think or feel when they finish the book?

Bells for Eli is a story of relationships and family dynamics, and I hope the story encourages readers to ponder the strengths and weaknesses inherent in all of us, especially the particular trials young people confront, no matter what generation (Baby Boomer, Generation X, Millennials, or what have you) they are born into. Certainly, Eli has more adversity to overcome than most young people, but there are deficiencies and flaws in the individual characters around him, and the overall culture of the small-town South in the ’60s has its troubling aspects also.

In a letter to his friend Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “The purpose of a work of fiction is to appeal to the lingering after-effects in the reader’s mind.” This is my purpose in Bells for Eli: for my characters’ lives to resonate with readers after the novel ends. To consider the irony of fate the novel presents: how it can take with one hand and give with the other. How wounds of the heart from childhood might never leave and become the catalyst for decisions that bring this novel to a staggering conclusion, yet simultaneously, how boundless love can ultimately triumph in a world where cruelty and pain threaten to dominate.

What advice do you have for anyone who wants to publish a novel at this age—45 and up?

Older writers have the advantage of more life experience and more years of reading. My advice is for older writers to embrace those advantages. To have lived and learned is invaluable in creating characters and their circumstances. Also, I believe anyone who wants to succeed at writing must read widely and constantly. What I know is what we read—I’m not talking about content so much as the words, sentences, style, tone, and effect—seeps into our subconscious and makes us better writers. You can take all the courses and get all the degrees in writing you want, but in the end, it’s reading that affects our writing most of all.

Older writers have the advantage of more life experience and more years of reading.

I need long blocks of time to write a novel. Some writers are superhuman, but I couldn’t carve out that time in my younger years when I was teaching English, raising daughters, and taking care of ailing parents, among many other things. Being older has afforded me more uninterrupted time to write.

What’s your next book?

I am writing a second novel, also located in the South, with the working title The Girl from the Red Rose Motel. It is set in 2013 rather than in a previous era as is Bells for Eli. The story revolves around a middle-aged, female, high school English teacher and two students, a successful white boy from a privileged background and a biracial girl with tremendous potential but from impoverished circumstances. The students meet during a day of in-school suspension. I’m enjoying the challenge of writing this novel from the viewpoint of each of these three characters as they find love and struggle with multiple conflicts, especially one between opportunity and hardship.

0 Comments