“I needed to understand the fear that overcame everyone who stayed in New York throughout the surge of March and April [ 2020] as hospitals in the city were overwhelmed—and to understand those whose lives are lived as a calling to save every life they can. I would discover that many of my questions would not have an easy answer: What draws people to fight for the common good in a crisis? How can people expose themselves to so much risk?”

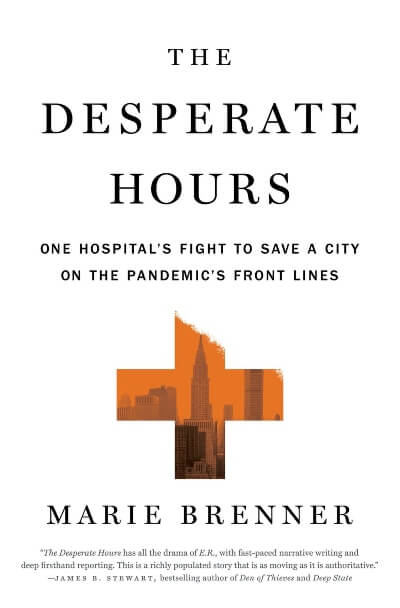

It was those questions—and this city—that Marie Brenner writes about in The Desperate Hours: One Hospital’s Fight to Save a City on the Pandemic’s Front Lines. If there was ever to be a soulful, passionate, thorough, movie-worthy history of the pandemic in New York City, and its desperate effect on a hospital system, this book was and is it.

Hear Marie Brenner talk about her extensive, unprecedented research for her new book. She’ll be joining us for a free, virtual NextTribe interview on Thursday, Aug. 11th. More info and save your spot here.

Just a little of what Marie saw: “On the expansive Columbia University Irving Medical Center campus between 165th and 168th Streets, where Nobel Prize winners have their labs, weeks were spent experimenting on ventilators to see if a single machine could support more than one patient. Masks were kept in locked cabinets to prevent stealing; sometimes nurses treating COVID patients broke down because even they could not get the masks. Fights broke out when only doctors were issued scrubs. Day care was arranged as well as transportation while nurses sobbed, holding the hands of the dying saying goodbye to their families on FaceTime. [Weill Cornell’s President and CEO Steven] Corwin frantically allocated and reallocated dwindling resources, begged government officials for help, and tried to rally his troops as best he could from his apartment. All this while New York-Presbyterian was undergoing a massive transformation of its electronic record-keeping.”

Marie Brenner considers herself “a story teller.” That’s quite an understatement.

The Opening

Author Marie Brenner

“It was amazing how it happened,” she effused to me on the phone, shortly before the dog days of late July. The Vanity Fair writer-at-large and prolific author had just returned to the city after a weekend in East Hampton, where she visited her two-and-a-half-year-old grandson Dash, the son of her daughter, author and journalist Casey Schwartz. (Casey’s father is the author, performer, and longtime radio personality Jonathan Schwartz. Marie has been happily married, since the mid-‘80s, to venture capitalist Ernie Pomerantz.)

“Dash greeted me with `Let’s put the bottle of champagne in the middle of the pool, Ri Ri!’” Marie says. “Where did that come from?!”

The hospital had never seen this level of death before.

Marie and I have known each other lightly for a number of years—and my son and her daughter have been friends. After we did the “fabulous-to-have-grandchildren!” lady-Boomer-writers phone dance, she went on with her enthusiastic account of how she scored the extraordinary access necessary to have interviewed almost 200 people, from cleaning women and morgue workers to major corporate heads, from anesthesiologists to warehouse managers to transplant transporters in the 10-campus Weill Cornell hospital system that sprawls through greater New York City.

“It was a happy accident,” she said, of her acquisition of the assignment. And she explained it: In the summer of 2020, she got a call from her agent Amanda Urban, known to all as “Binky,” to say that Weill president Corwin wanted—quite astonishingly—to “open the kimono” and have a journalist speak to as many people as possible in the massive hospital system and tell the story of its dramatic and highly challenged response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Corwin didn’t want all that happened to the doctors and front-line workers to go into amnesia,” she explained. This was particularly impressive since several bold staffers had, during the prior months, gone public with news of how crushingly difficult it was to make it through the pandemic and they had been punished for speaking out, in some cases losing part of their pay and job functions. But Corwin—“a brilliant cardiologist who is an amateur historian”—wanted to be truthful. He had put the word out through his chief strategy officer and eventually got to Binky Urban, who wholeheartedly endorsed Marie.

I said, “Can I start tomorrow?!” Marie recalls. “ It was an incredible privilege to be a kind of Trojan horse—to go in and really see what happened.”

As a business, Weill Cornell was heroic, she soon learned. “They went into tremendous debt but they [eventually] really pulled themselves out of it. They organized this billion-dollar volunteer effort and hotel rooms and 37,000 meals for their employees. They had never seen this level of death before, [especially with] the incredible lunacy from the White House and this surreal atmosphere” that accompanied it.

The Life Savers

Through the book we meet many dozens of what Marie calls “quirky people with their `Humans Of New York’-style back stories” and a breathless heroism. Some of them? Victor Holness, the morgue director who had been an illustrator for the ‘70s alternative weekly, The Village Voice, and now found a way to arrange the bodies in his domain—on a moving machine “like a cleaners’ rack”—in a way that made it easier to store the daunting overflow of them.

Another: Dr. Kenneth Prager, the 80-year-old chair of the medical ethics committee and a pulmonology authority whose brother, Dennis Prager, was a well known pro-Trump broadcaster and whose son was the author of a book on Roe v. Wade.

Returning to the death-filled hospital work of saving other lives after her own sister and nephew had perished took tremendous courage.

Yet another: Nathaniel Hupert, the Harvard-educated son of an artist and a museum director who was a master “modeler” of Weill Cornell. (As a modeler, he was charged with mathematically predicting how the spread of COVID would affect the hospital.) Then there was Felix Khusid, the son of Russian refuseniks who came to New York at 16, worked in a homeless shelter and got a job as a house cleaner before becoming a respiratory therapist. (“His basement office in Brooklyn was like a little museum of every kind of ventilator from the nineteenth century on,” Marie said.)

And Matt McCarthy, a scholarship undergraduate at Yale who became a pitcher on the farm team of the Anaheim Angels and then moved on to Harvard Medical School, became one of the world’s experts on bacteria, and wrote a number of bestselling books. (McCarthy was demoted for going on TV’s Squwak Box and talking about the true state of disaster the hospital was facing.)

And of course there were many extraordinary women. Among them: Dr. Lindsay Lief, the daughter of Holocaust survivors; the mother of children named Freedom and Mandela; and the director of one of Weill Cornell’s six ICUs. Lief oversaw a large team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, technicians, and patient transporters—and she served selflessly at the unbelievably busy white-hot center of receiving and treating the COVID patients. (For Lief, Marie writes, “there hadn’t been even a moment to step back and wonder what was going on outside…[That] world had vanished; the only evidence of its existence was what seemed like a ceaseless avalanche of dying patients.”)

Then there was Veronica Roye, a dynamic Black ICU nurse, transplant transporter, and doctoral candidate who, because of the immense legacy of Blacks being treated criminally in terms of experimental drugs, long resisted being vaccinated against COVID. When she asked Corwin to publicly denounce the killing of George Floyd, he heartily agreed.

Another elegantly resilient woman was Dr. Kerry Kennedy Meltzer, first year medical resident and the young daughter of Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, who continued to work against the onslaught of COVID death even after her slightly older sister Maeve Kennedy McKean and her young son Gideon died in April of the pandemic year, when a fluke storm overcame their row boat in the Chesapeake Bay. Kerry was intensely bonded to Maeve, whose work in global health had influenced her to go into medicine. Returning to the death-filled hospital work of saving other lives after Maeve and Gideon perished took tremendous courage and love on Kerry’s part.

Generosity and Resilience

Marie documented these and dozens of others whose generosity and resilience were extraordinary. Those who gave well beyond the limits of what seemed possible to give, rising hours before dawn, working multiple shifts, getting COVID themselves (some dying from it); sadly parking their children with relatives for months at a time; worrying about (and working desperately against) the surge of the pandemic, trying mightily for sensible triage plans amid an onslaught of cases and the certainty that some would die for lack of resources, and disobeying the hospital’s policy of censoring the extent of the surge and the unpreparedness of the system.

People were wearing scuba gear and doing their best, and their best was not good enough.

“Of course,” she wrote, “a version of this happened at almost every hospital in America. But in New York, at the city’s most elite hospital system, it happened before it happened anywhere else and with both greater velocity and catastrophe. ‘However bad you think it was, it was so much worse,’ Dr. Elizabeth Oelsner said. The press did not get the half of it. People were wearing scuba gear and they were showing up and they were doing their best, and their best was not good enough. And you knew that the disease was so bad so many were going to die no matter how good you were.”

Researching and writing the book—driving up to the main Weill campus on West 168 Street daily, during the surge, interviewing the far-flung team, many of whom had inspiring up-from-their-boot straps stories and came from countries as diverse as Ukraine, Colombia, Japan, India, Barbados, China, and the Dominican Republic—warmed her heart to a major player in the saga. “I loved New York in a new and bigger way than I ever had before,” Marie says. “What a city!”

Her sources were “in various states of trying to understand what they had been through. Some were still so traumatized they bristled at my questions. Others burst into tears and felt relieved to be able to speak at last. Most were in a state of shock, dealing with all the complexities of the United States of Immortality: the anxieties around mortality that can affect doctors and health care workers. They had never seen so much death—nor so much denial and so much hideous policy as the Trump administration showed. And they felt unprepared in every way to deal with it. Some were so depressed and raging that they were being used as collateral damage. Others felt this surge of exhilaration—‘the rapture of action’ —after the first few weeks of helping each other through. Truly, it was the reporting experience of a lifetime.”

In New York especially—as in most major cities—the heads of the hospitals are power brokers of the highest order, and Brenner saw and documented this. “One of the great Robert Caro characters” was Ken Raske. “He came from a penniless family in Michigan and rose to become one of the most powerful people in New York. He’s the chief lobbyist for hospitals in the state. He pulled the five hospitals together and fought for funding to save them.” Fortunately, it worked.

A Signal Tragedy

Among the many dramatic moments in the book was the intense pain over the practicality and ethics of triage policy—when there weren’t enough ventilators, who would get them? In this war-like state, one could not legally leave a very sick 85 year old without a ventilator, even though that situation would leave the ventilator-deprived younger patient without the chance to be saved. There was much trial and error, such as experiments with special clamps for lung inflammations—now standard treatment for covid; experiments with using one ventilator for two patients; experiments with packing bodies in morgues, experiments made in the heat of deathly illness. The book explodes with them.

A signal tragedy was the suicide—on April 27—of Lorna Breen, the medical director of New York-Presbyterian’s ER. The unjustified weight of guilt in not being able to save every one of her patients was that fierce. I remember her smiling face in the New York Times photo published after her death. To have worked so hard to save others and then kill yourself for failing at the impossible: an insuperable tragedy.

Marie dedicated her book to “all the children and grandchildren of New York-Presbyterian’s front lines who will someday learn of their parents’ and grandparents’ roles in the saving of lives.”

Pain and Laughter

Less than two weeks after I spoke to Marie, COVID cases were once again up in the city. “COVID will be with us for a long time,” she says. “But, at the moment, however many cases there are, they are less virulent. This could mutate at any time, and then, as one of the epidemiologists recently said, `We are fucked.’ He gives it about a forty percent chance. So far the hospitals are able to handle it, but the big worry is all the burn-out of hospital teams.” Still, Marie is optimistic. America is a country of optimists and can-do experts—and New York is a city of the same. She has seen, and documented, this again and again.

Writing about death is an enterprise for the heroically thick-skinned.

Marie had come to New York from San Antonio in the ‘70s, where her grandfather owned a major department store, by way of the University of Pennsylvania. Her current husband, Ernie, is also a San Antonian. “We were introduced after both of us were divorced [from their first spouses]. And voila ! A lot of tamales and trips home.”

I ask Marie which, of her own seven previous books she felt the proudest of or most attached to.

She wrote a number of books that might be said to comport with being a socially with-it, Hollywood-connected writer during those years (Going Hollywood: An Insider’s Look at Power and Pretense in the Movie Business; Tell Me Everything), as well as a history of a media empire, the Bingham family of Louisville; a book, Great Dames: What I Learned from Older Women, that gave us a window into the charms and wiles of the likes of Diana Vreeland and Clare Booth Luce; and her biography of war correspondent Marie Colvin—Marie Colvin’s Private War—gave us an extraordinary view of this iconic war correspondent.

But Marie’s personal favorite, before The Desperate Hours, is Apples and Oranges, her 2008 memoir “of coming together with my factious older brother in mid-life,” she says. “He was very conservative, I was not. But we had a fierce connection—a loyalty to one another. Anger was our soundtrack until he got a rare cancer at 50 and he and I traveled the world looking for a cure for the disease that would ultimately kill him at 55.” Where did the title come from? “He was a trial lawyer who became an apple orchardist, first in South America, then in Washington State. Sibling death is not written about enough. I was trying to deal with coming to terms with losing a brother who was still so young. I had a real sense of survivors’ guilt and a feeling that I had lost my own place in the world.”

Writing about death—whether in pandemic hospitals or in families—is an enterprise for the heroically thick-skinned. Marie Brenner is such a woman. Like many women our general age, her respite from work, even loved and important work, comes in family. “My beloved Dash!” she says, of her grandson. “I just want to write down his every question and hilarious remark, as he discovers the world. I want to laugh and laugh.

“And: I do.”

I second that emotion, and I thank Marie for the reminder that even among death, laughter and joy can still be found.

Read More: Another Reason to Love Dolly Parton: She Helped Fund a COVID Vaccine

0 Comments