When I looked up to the summit of the highest point on the Inca Trail, the figures were in silhouette, hardly distinguishable. But their voices were clear—and especially inspiring. Over and over they were singing the chorus from the Supreme’s hit: “Ain’t no mountain high enough, Ain’t no valley low enough, Ain’t no river wide enough, to keep me from getting to you, love.”

NextTribe is offering you the chance to hike the Inca Trail in 2024. You too could achieve more than you thought possible and see one of the wonders of the world in the most rewarding way. Join us on Monday, Nov. 20th for an info session with women who hiked with us in 2022. Click here for details.

The words were intended for two of our group, who were struggling up to the top of the unhelpfully named Dead Woman’s Pass, altitude almost 14,000 feet. This was the hardest part of the NextTribe four-day-three-night hike over the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. We had started the day at a camp at 9,500 feet, which meant in only a few hours we were climbing 4,500 feet in elevation. Ten of us had been waiting at the top for our pair of sisters, Sharon and Sondra, who had come from Texas to take this journey with NextTribe. The two guides on this trek were hanging with the pair, making sure they felt supported and as comfortable as possible the whole way up.

When we spotted them nearing the summit, I went down to meet them and offer as much encouragement as possible. That’s when I looked up and saw the rest of our crew doing their best Diana Ross impressions. “The singing made all the difference,” Sharon said. “It buoyed me.”

When the sisters made it to the top, the tears flowed. Not just from Sharon and Sondra, who were overwhelmed by their own achievement. But also from the rest of us, who were deeply touched to witness the struggle and the eventual conquering of a difficult goal. We were also crying that all of our group had made it to one of the most challenging spot on the planet. We had done it, the 12 of us, and we had done it together.

Read More: On the Way to Machu Picchu: The Dead Woman and the Turn-Around Lady

Where to Start the Inca Trail

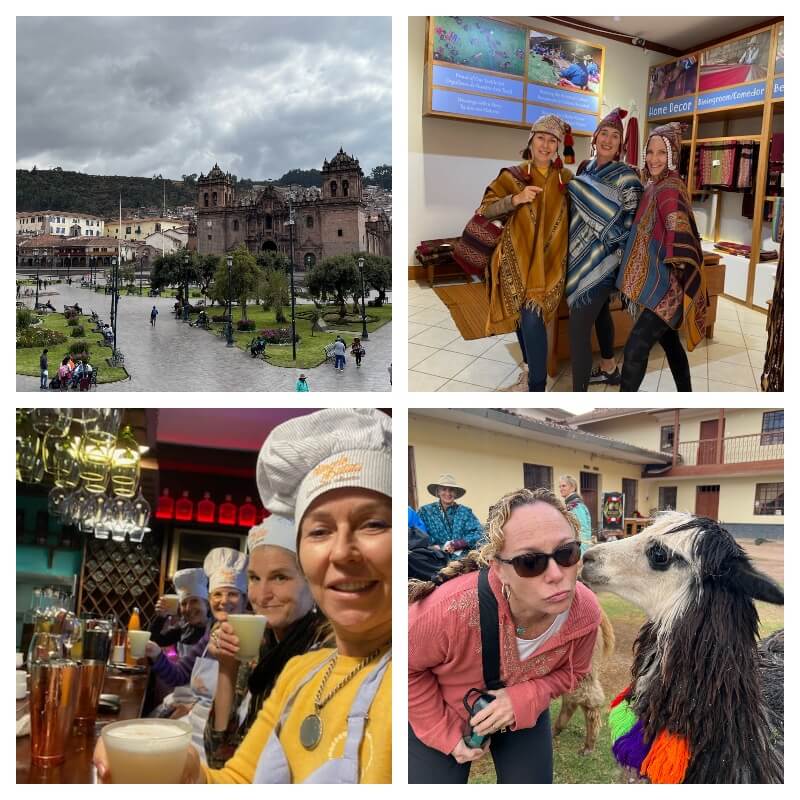

Clockwise from upper left: Historic Cusco: modeling purchases at the Center for Traditional Weaving: getting llama kisses: sampling the pisco sours made in our Peruvian cooking class.

I could have started this story one hundred ways. There were so many moments that exemplified the experience of this group of NextTribe women who hiked 26 miles over four days to get to one of the modern wonders of the world—the iconic, mind-blowing Incan settlement known as Machu Picchu. But the drama of Sharon and Sondra making it to the top of Dead Woman’s Pass perfectly encompassed the three elements that were expended to make this grueling trek.

I had put together the itinerary for this hike late last year, after hearing from some of our regular travelers that they would love something more challenging. Our other trips are fun and enlightening, no doubt—exploring San Miguel de Allende, Mexico during Dias de Los Muertos, lolling on a beach on the Pacific, visiting the nooks and crannies of Paris on our Neighborhood Tour—but not necessarily physical.

I knew the trek required great physical exertion and mental toughness. I also knew that it was well worth the effort.

I had hiked the Inca Trail 13 years ago with my then-husband and my two children, ages 12 and 10 at the time. I knew it required great physical exertion and mental toughness. I also knew that the reward of standing at the Sun Gate and peering down to see in real life one of the most photographed places on Earth was well worth the effort.

Many of the women who signed up did so because this was a bucket-list item. We all spent months doing some type of training on our own–more hiking, more cardio, more stairs, more time at altitude or all of the above. At least two of us traveled to Colorado to get accustomed to high altitude.

The 12 of us came together in the gorgeous Peruvian city of Cusco two days in advance of the start of our hike; several of us had arrived four days early to have more time to adjust to the altitude, which is 11,200 feet. The time in Cusco was put to good use. Many of us took a Peruvian cooking class where we learned about the culture through culinary traditions and learned how to make ceviche, lomo saltando, and pisco sours. We visited a textile center where we watched traditional weavers work their craft and then bought pieces of their work. At a demonstration of traditional music at the Inca Museum, we heard the haunting, affecting notes made by centuries-old instruments. We ate well, drank well, and shopped well. And oh yes, on our walking tour of the city, we were taken to a pasture, where the llamas kiss your cheek.

Then, at 5:30 on a Tuesday morning, our outfitter, SAS Travel Peru, picked us up in a bus at our Cusco hotel and took us to Ollayntambo, a three-hour drive from Cusco, to start our hike. This is when things got real.

What to Expect When Hiking the Inca Trail

Number one: Get ready for some major bonding with other hikers.

Clockwise from upper left: Words of encouragement, a gift from Christine, a.k.a. McGyver; the start of our trek; we’re all in this together; the route we’ll be taking.

When I first heard our head guide Rojo use the word “family,” I thought it was a mistake. I suspected he looked up a word for “group of people” in his English dictionary, found the word “family,” and ran with it. “OK, family, here’s what we’re going to do,” Rojo said at a meeting in a Cusco hotel the night before our departure for the Inca Trail. He was a large, affable man who one of us would later describe as an Incan King, and we would come to discover that his word choice—which he would use over and over in the next few days—was no mistake. He would use it again and again on the trail.

It took no time to see how we were developing into a fiercely supportive and loving clan. On the first day, when we stopped to look at an Incan Ruin along the route, many of us noticed, almost simultaneously, that one of our group was missing. We began searching for her frantically, only to eventually find that Olga (who later be nicknamed “The Big O” for her name and her bright orange pants) was sitting cross-legged on the other side of a wall, meditating as she looked out over the sharp, glacier-topped mountains. That night at camp, as we all lay in our tents in the crisp mountain air, we did the bedtime routine from the Waltons. “Good night John Boy!” I shouted into the silence, which elicted snickers and the expected echoes of “Good night Mary Ellen,” etc.

There were many times along the way that we would break into the most apt song: “We are family/I’ve got all my sisters with me.”

From the start, we shared any item necessary for the success of the group. If someone was low on water, there were 11 others to provide it. If someone was struggling with the altitude, coca leaves or coca candy was delivered right away. We reached into each other’s backpacks to retrieve things so that the wearer wouldn’t have to remove the pack. When it rained the first day, we helped each other don rain ponchos, which tended to flap wildly in the gusts of wind. We hung each other’s wet clothes out to dry; we alerted those behind us to dips or dangerous terrain they would encounter.

Clockwise from upper left: The view out my tent; dinner is served; our incredible chef Pedro; our guide Rojo with one of the delicious (and beautifully garnished) dishes made on a camp stove.

It wasn’t long before we were using the term “Family” in the same way Rojo did. “Family! Let’s go over here to do some stretching and yoga before we start today,” I’d say to the group. Or someone would shout out, “Family! Who has bug spray?” There were many times along the way that we would break into the most apt song: “We are family/I’ve got all my sisters with me.”

By lunch on the third day, I had to stop to laugh at the level of comfort we felt with each other. Meals were served, appropriately enough, family style; heaping plates of gorgeous food—at least eight dishes at lunch and dinner—were passed around. On this day, excitement was high since we knew the next day we’d be at Machu Picchu, and we were all talking at the same time. Just like a large rowdy family, we had to yell at each other two or three times to get someone’s attention. “Hey, Flora, pass the rice!” “Is there any more hot chocolate?” “Hey Ellesor, I need some salt.”

In turn, we developed nicknames for each other. Rojo gave me the name “Jefecita,” which means woman boss, though others called me “Tooter,” because of the effect altitude has on my gastrointestinal track. I’ll give other nicknames below, but Ellesor, my friend from college, got the name “C.B.” for Chatter Box because she was able to keep the trail conversation going on and on. (Just for the record, Rojo sometimes veered from calling us “Family.” We got the moniker “Sexy Llamas” as well, which we liked very much.)

Those trail conversations served as a distraction when the going got tough, but also became our glue. You get to know someone in a new and deeper way when you are under pressure with them. Hearts and histories open up.

How Difficult is the Inca Trail?

The exertion required to make this journey was more than many of us expected.

There are easier ways to see Machu Picchu. Trains take thousands of people a day on the nearly four-hour journey from Cusco. But there is no more rewarding way than to walk in the footsteps of the Incas, who for 70 years made a pilgrimage over the same ground in the 1500s, we were told. I had tried to prepare the group for what would be required of them, and I focused mainly on Dead Woman’s Pass, which for me had been by far the hardest part of the experience. (Fortunately 17 porters were carrying our belongings, including our tents, sleeping bags and all our food for the trip; we only were carrying essentials like sunscreen, water, snacks and rain gear.)

Dead Woman’s Pass

Clockwise from upper left: Olga, resting on the demanding climb up Dead Woman’s Pass; Jeannie and Ellesor summiting together; the group gathered to celebrate; our relief and joy when Sandra and Sharon made it to the top.

Some of us didn’t sleep well the night before we were to climb the pass, me included. Our guides had told us over and over that it wasn’t a race, that we could take the time we needed, and if we took the tortoise approach to the incline, we were more likely to make it. Quite a few were on a medication called Diamox to help their blood better absorb oxygen.

And for most, Dead Woman’s Pass–which earned the name because the mountain looks like a female lying down not because anyone died there–more than lived up to its advertised difficulty level. One rise along the ridge had the shape of a breast, complete with a small nipple. “Keep your eye on the titty,” Flora (also known as “Yard Sale” because of the number of things hanging off her day pack) shouted as we got to the steep part and our goal seemed almost unreachably far.

To make sure we all reached the summit, the guides, Rojo and Edwin, kept reminding us to slow down and to sip water often. We also shared coca leaves to chew on and candy derived from coca to suck on. I suggested to a couple in our group who had started out fast that they need to pace themselves better and I hung back with about six of the group to help establish a reasonable rhythm.

“The hardest part is over!” I declared when we all gathered at the top. This wasn’t true.

We took the trail in zig-zags, walking sideways across the path, then turning and crossing in the other direction We did what we called the “wedding march,” where one foot meets the other briefly before moving forward. This helped us be more mindful. My son, who lives at altitude in Leadville, CO, suggested I tell the hikers to breath in through the nose—which helps bring oxygen to the brain faster—and out through the mouth. Whatever else it did for us, the breathing practice was very calming and helped keep our minds off the exertion.

Our pace was plodding, the air was thin, our muscles ached, but a mitigating factor was this: we weren’t alone. Not only did we have our group for support, but there were other people on the trail we came to know. Another group of women our age, in fact. (Curiously, most of those we encountered along the way were women.) After hours on the climb, we made it to the summit. I held the hand of my college friend Ellesor, and those who made it first waited for the entire group, offering support like singing to ease the way.

“The hardest part is over!” I declared when we all gathered at the top. This was my experience when I’d hiked the trail 13 years ago, but it wasn’t quite true for others in the group this time. The down hill following the summit was steep, with many ragged stone stairs. It was brutal on knees and hips, and shoes too. Halfway down, Emily, a marathon runner from New York, halted suddenly because the sole of one of her hiking shoes had partially come off. At each step, the loose sole flapped like a crocodile jaw. To the rescue came Christine from Chicago, who we all called “McGyver” because she had such a complete arsenal of handy tools. McGyver taped up Emily’s boot and on we went. From then on Emily’s nickname was “One Shoe.”

The downhill was so hard for some that it was well after dark when four of our group got to camp. Our guides had stayed with them the whole time and two NextTribers were assisted by porters, who took their backpacks and one arm and halfway skated them down the mountain. We all slept hard that night.

The Second Mountain

Clockwise from upper left: The steep downhill after Dead Woman’s Pass; another perspective on how going down can be as hard as going up; getting passed by one of the female porters on the trail; our guide Rojo playing the traditional flute to help us climb the second mountain.

The next day we climbed another mountain, slightly less high than Dead Woman’s Pass. The last time I did the trail, I had done both mountains in one day, but I realized there was no way this group could have done so. Our guide Rojo played the Peruvian flute from the summit of the second mountain as we slowly moved up the trail below him, which helped ease the way. When we all were on top, I asked everyone to take a moment to thank their incredible bodies for the hard work, for doing more than we knew it could accomplish. I was particularly grateful that my body had held up well in the 13 years since I last did the Inca Trail; the route seemed actually easier than before, probably because I work out more now and was taking the hike more slowly and sensibly.

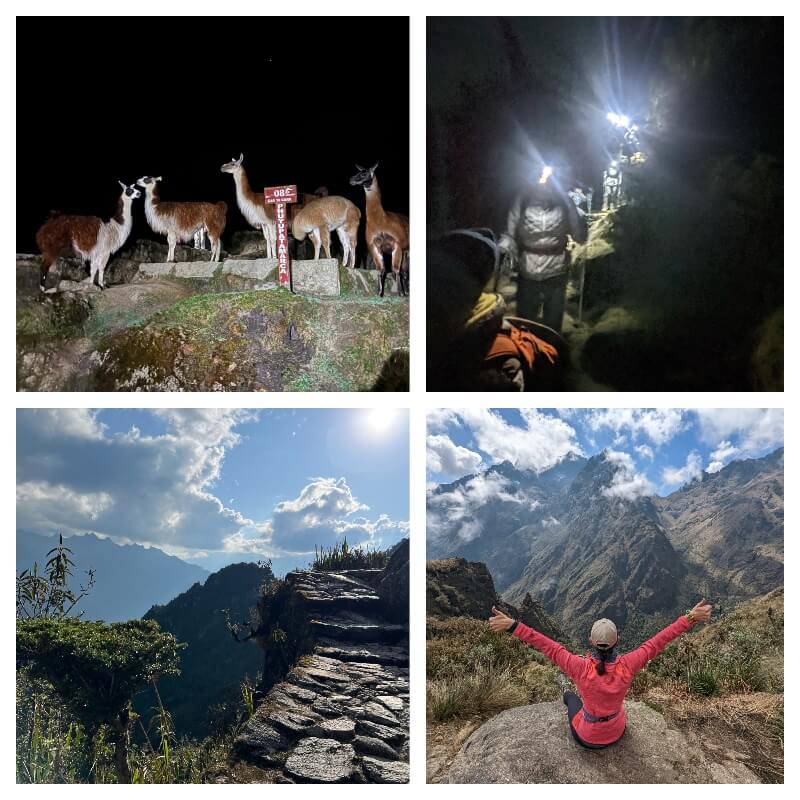

As were were leaving, our headlamps shone on a pack of elegant llamas, who seemed thoroughly confused as to why we were disturbing their sleep.

On the third night, we camped in the most splendid spot, high on a ridge with views of mountain tops as far as we could see (and, strangely, a cell signal!). We went to sleep early, because of exhaustion and also because we had to get up at 2:30 am the next morning. Our porters were on a strict schedule and had to finish the route by a certain time the next day. This meant the next morning we had to walk down a steep drop in elevation, over potentially slippery stone steps for about two hours, with only our headlights to illuminate the way.

I was concerned with how our group would fare over this rugged terrain, but our adrenaline was high—we were going to see Machu Picchu that day. Plus we had a good send off from our camp site. As were were leaving, our headlamps shone on a pack of elegant llamas, who seemed thoroughly confused as to why we were disturbing their sleep. The line of headlamps behind me as we gingerly descended made me feel we were space explorers on a strange planet, like in the movie Aliens.

The Sun Gate

Emily, a marathoner from New York, walked so much she blew out the sole of her hiking boot. Her nickname became “One Shoe.”

When we were told we were nearing the Sun Gate, the pass above Machu Picchu that Incans crossed to finish their journey, our pace quickened, as if we were horses near the barn. Even though my quads and calves were screaming and the soles of my feet felt battered, my muscles kept cranking, as if every fiber in my body knew I was close.

The monkey climb is about 50 yards of steps that are so vertical the only way to ascend is by using hands and feet to pick your way up.

I had forgotten that one challenge remained. The “monkey climb,” or as our guides called it, “the gringo killer.” The monkey climb is about 50 yards of steps that are so vertical the only way to ascend is by using hands and feet to pick your way up. It was the last obstacle and because it was unexpected, I heard some cursing, maybe some of it directed at me for failing to recall this.

From there it was almost a sprint to the Sun Gate, the place where you step out to the end of a platform to see one of the world’s most photographed spots in real life. Nothing quite prepares you for the majesty of it, the realization that this spot spread below, with the gumdrop mountain to one side, lies before you the same way it has been doing so for the past 700 years.

Fast moving low clouds kept enveloping the view below and eliciting fleeting comparisons to Brigadoon, but just as fast, the clouds would clear to confirm that you weren’t dreaming.

The Prize

Clockwise from top left: Llamas sent us off on our 2:30 a.m. hike the last day; headlamps were the only light we had hiking a treacherous downhill stretch; Menke, “the GOAT,” soaking in the view; the Inca Trail still intact for more than 700 years.

Another hour’s walk, down a mostly gentle incline, and we were at Machu Picchu itself. Actually there. We posed for pictures and rejoiced. We made our way through the throngs of visitors who had arrived at the site via train or tour bus, and we heard tour guides tell their groups that we had walked the whole way to Machu Picchu. We noticed people stepping back to take a look in something approaching awe (or maybe it was our smell after three days without a shower). Many congratulated us.

An unexpected sensation took hold—more than pride, maybe a sense of superiority, if we’re being honest.

An unexpected sensation took hold—more than pride, maybe a sense of superiority, if we’re being honest. “We earned this,” Courtney (a.k.a “C.C.,” for Compassionate Courtney) said. “We put in the work to get here.” Work, and a lot of sweat.

Is it Worth Hiking the Inca Trail?

If the copious tears of joy are any indication, then yes, is is worth hiking the Inca Trail.

Joy, relief and disbelief as sisters Sondra and Sharon reach the Sun Gate and first lay eyes on one of the Wonders of the World.

The first time I cried on this trip was at our hotel in Cusco. Once all parties had arrived safely from the States, the 12 of us met in the breakfast room. We went over the plans, and I gave out some gifts to each person—a tiny notebook to record thoughts plus a can of oxygen to ensure that we all made it. Then out of the blue, Christine (“McGyver”) brought out her own gifts. She’d had 12 bracelets made that said “You Got This!” I felt my eyes watering because the gesture was so thoughtful, so inspiring, and just the kind of camaraderie I love to see among women our age.

Nothing was more affecting than when Sondra and Sharon, our sister team reached the Sun Gate.

Each mountain top and hurdle became a reason to tear up. We cried for relief and the sense of achievement. Several of the group cried or came close to it when they got to camp on the second day after the excruciating downhill. “I’m just spent,” said Denise (nickname “Poka in Hokas” for her fat braid and choice of footwear). Or maybe people were crying at the very sorry state of the toilets at that particular camp.

Nothing was more moving than when Sondra and Sharon, our sister team (a.k.a, respectively, “Sissy” and “Ziggy,” for the zig-zagging that enabled her to conquer two mountains) reached the Sun Gate. After so much work, so much discipline and determination, so much mind-over-matter, they were both completely overwhelmed to finally reach their destination. They fell into each other’s arms and peered at the sight before them as if they were looking onto the Pearly Gates. No one witnessing this could keep a dry eye.

Tears of Laughter

The “family” lodgings for 3 nights.

Almost as often our tears were from laughter. We were punchy most of the time and we were not immune from bathroom humor. What tickled us most was the products people brought to make peeing on the trail easier. Jean packed a plastic “penis” that allowed her to pee standing up. Maybe for this reason we felt we needed to clarify her sex by giving her the nickname “Lady Jean.” Several hikers carried something called a pee pad (with the tagline “Piss Off” printed on the product), which was supposed to keep you clean and dry after bathroom breaks in the wilderness. We could barely contain our snickers when a bellman at our hotel near Machu Picchu found one on the floor while handling our bags. “Whose is this?” he wanted to know, holding it up by two fingers. The youngest member of our group, Menke (“the GOAT” for her climbing prowess), stepped forward sheepishly.

Lady Jean piped up “If it looks like ham, and tastes like ham, it must be guinea pig!”

Rojo, our guide, was a jokester and often told us while passing platters to us at meal time that this dish was baby condor or that one was guinea pig (which is a traditional staple of some Peruvians). At one point, Lady Jean piped up “If it looks like ham, and tastes like ham, it must be guinea pig!” We all had a big time when Ellesor (“C.B.”) thought she’d caught one of us in some naughty business. A porter walked by us one morning and complained to Rojo that something in the pack he was carrying was vibrating and making him crazy. As he unpacked his load, Ellesor announced that she was eager to find out who had packed a sex toy for the trip. Soon enough, the source of the vibrating was discovered to be Ellesor’s electric toothbrush.

I know I let go with a few boo-hoos during my massage at the end of our trek. We ended our Machu Picchu adventure by staying at the super luxurious Belmond Sanctuary Lodge, which is directly at the entrance to Machu Picchu. This was our reward for the demanding days of deprivation. We all scheduled massages and never before had a rubdown felt better or more deserved. (The sumptuous beds and the availability of pisco sours and wine were also cause for tearful celebration.)

Saying Good-Bye

From top left: Climbing the Monkey Stairs (a.k.a: Gringo Killer); Jean showing us the million-dollar view from the Sun Gate; Jeannie and Ellesor exploring the ruins; the very exhausted, very proud group at our destination.

Probably the most tears were shed when we said good-bye to our guides and later, each other. At one of our last group photos, Edwin our guide was scrunched together with us for the camera. Several of us were shouting, “We love you Edwin!” and the like. Then just at a quiet moment (a rare quiet moment, I should add), we heard Edwin say in almost a whisper, “I love you, tooooooo,” with the last word rising up melodically.

Many of the group called the trip life-changing since it showed them all they were still capable of.

The break up of our “family” is something that is still hard to get over. We have a text thread that is filled with photos, memories, and comments about how our bodies and souls are missing Peru and each other. Many of the group called the trip life-changing since it showed them all they were still capable of. “Good morning,” Courtney (“C.C.”) wrote last week. “To think this time last week, we were on our way to the Sun Gate…some of us a little bruised, tired, and sore…but doing it as a community, together. We supported each other when we needed it the most. Now, looking back, I realize more than ever how incredibly special those days were with each of y’all. Thank you for the companionship, friendship, and laughs along the way. I couldn’t have asked for a better group of women to do the Inca Trail with. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve found myself sifting through the photos of our adventure, wishing I was back in Peru.”

Sharon (“Ziggy”) sent me a quote she’d found about Dead Woman’s Pass, also called Warmiwanusqa. “For those who find the inner-strength and mental toughness, reaching Warmiwañusqa is a significant psychological and physical milestone. It is an accomplishment that few people in the world undertake—a sign of focus, recognition of the power of their environment and the depth of history, and the inner strength required to accomplish something significant to one’s well-being.”

Then she added her own thoughts: “I felt that we all left a piece of ourselves on that trail and pilgrimage. I know I did for sure. I left my footprints, my breath, my handprints, my hopes and dreams, my effort and life force…..these will forever be a part of the trek and that trail.” And each other.

Read More: Feeling Like Excited Kids Again on a Girls’ Beach Retreat

Left: The group at our favorite Incan site–one that can only be seen if you walk the Inca Trail. Winay Wayna is far from the crowds of Machu Picchu. Right: Gathering as a “family” before heading down from the Sun Gate to Machu Picchu.

0 Comments