***

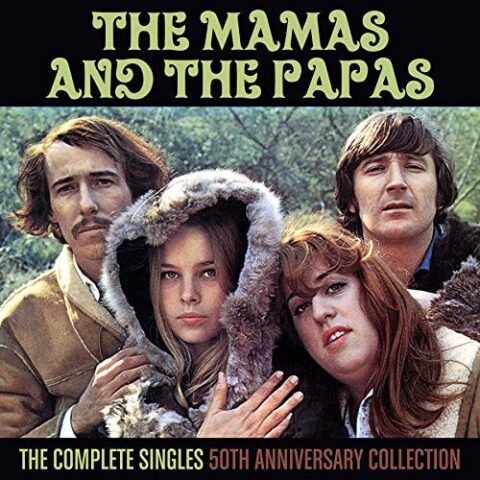

From 1965 to 1968, The Mamas and The Papas, a pop singing group, turned folk-rock into the music of the barely-pre-psychedelic counterculture. With hit songs like “Go Where You Wanna Go,” “Monday, Monday,” and the super-iconic “California Dreaming,” they seemed cannon-shot onto the airwaves when the country was still shaking off its post-Camelot conventions. Girls were wearing go-go boots; boys were growing out their early-Beatles haircuts. No group had ever looked like them: two sexy Ichabod Cranes in funny hats (very tall leader John Phillips and tenor Denny Doherty); a pouty blond beauty (Michelle Phillips), and, perhaps most arrestingly, a magnetic fat girl: Cass Elliot.

No group had ever sounded like them, either: Denny’s aching choirboy voice and Cass’s wry-beyond-her-years alto lacing through that creamy, 1950’s-prom-worthy close harmony. They used Papa and Mama in front of their first names (this was Cass’s idea) and evinced an air of inside-joke-filled, rich-hippie family.

John Phillips, with his tough ego and hyper-controlling nature, knew he was the leader. He had put the group together, had a military background, and was entrepreneurial enough to have co-started the Monterey Pop Festival. But it emerged very early on that the star of the group was the last to be asked to join—she had to push her way in—and the most unlikely: Mama Cass.

In an unforgiving era when you weren’t supposed to be a fat or unbeautiful female pop singer—especially, perhaps, when you were standing next to the most gorgeous, thin blond in all of entertainment—Cass was both. And at a time when the music industry, even worse than so many others, played by men’s rules only, Cass out-did leader John Phillips in the charisma category and emerged as the famous one, the focus-puller. Fans loved Mama Cass —her warm voice with a hint of irony, her innate-seeming confidence. “I think she was the most famous because she was the most identifiable,” her daughter Owen Elliot-Kugell, 51, confided to NextTribe.

The Unlikely Star

Cass seemed so confident that she gave that quality to others, even to those you would think did not need it. “I adored Cass from the moment I met her,” Michelle Phillips told me recently. “She would always encourage me to go for the note [when we sang]: `Go for it! You can do it! I know you’re gonna make it! I’ll be there for you!’ She was also very protective of me and assertive for me where John was concerned. She said, `Don’t let him boss you around like that! You are Michelle! You cannot be afraid of him!’ I felt very insecure because I met and married him when I was in high school.” Michelle went on to have a romance with Jack Nicholson and a years-long, near-marriage to Warren Beatty, so she would not seem to be the insecure type. “[But John] could be belittling. Cass helped me with my self-esteem, forcefully.”

Cass was also the leading salon-holder and advice-giver in storied Laurel Canyon. Graham Nash zoomed right to her for counsel the minute he got off the plane from England; Joni Mitchell was one of her best friends; and the group Crosby, Stills & Nash—one theory goes—was formed in Cass’s home. Everyone loved Cass, who was able to parade such authority despite private humiliating pain.

Aside from breaking the weight-shaming stigma and rising as an improbable female icon, Cass was other things young women weren’t allowed to be then but can be now—a proud single-mother-by-choice and a working mother who supported her child alone.

Owen Elliot-Kugell has never talked about her mother much in print before, but she feels it’s “my mom’s time” now. She sees her as blazing the trail for being a female pop superstar who was, frankly, fat. “Without my mom, there might not be an Adele—or, in comedy, Aidy Bryant on Saturday Night Live,” Owen tells NextTribe.

Today there’s a happy, hardy fan and media war against the shaming of obese women. Actress Gabourey Sidibe is adored. And, as Kate Pearson on This Is Us, Chrissy Metz wields utter self-confidence and the ability to give advice to others, who snap-to when she does so. Her brothers lean on her, and her husband Toby is head over heels in love with her in almost every scene they have together. The show makes an obvious point of saying, “Obesity will not get in the way of this proud, fabulous woman, even in terms of pregnancy—so there!” In addition, well-known yoga instructor Dana Falsetti and others like her have changed the paradigm for looks in body-brandishing female sports. A case could be made that Cass Elliot pioneered all this.

Aside from breaking the weight-shaming stigma and rising as an improbable female icon, Cass was other things young women weren’t allowed to be then but can be now—a proud single-mother-by-choice and a working mother who supported her child alone.

“She was a one-woman triumph against adversity; she was ahead of her time; women now are finally doing what she did 50 years ago,” says Owen, who lives in L.A. with her record producer husband Jack Kugell and their kids Zoe, 19, and Noah, 16. “I look back on her and realize that, just by example, she taught me, and others, not to accept it when someone says you can’t do something.”

On Broadway

Cass—Ellen Naomi Cohen—was a middle-class Jewish girl from Baltimore who left high school six months before graduation to go to New York and try Broadway. She lost the role of Mrs. Marmelstein in I Can Get It For You Wholesale to a budding young Jewish singer-actress who did her share to establish the rule that you didn’t have to be classically beautiful to be a star: Barbra Streisand. Cass then got a job as a coat check girl at a Manhattan nightclub, the Bitter End, singing and trying to get random agents’ attention, as she juggled hangers and quarters as tips. She met folk singer Denny Doherty at the club and “drank him under the table,” Owen says.

“My mother was The Little Engine That Could,” Owen says.

Cass developed an unrequited crush on Doherty, followed him down to the Virgin Islands, and talked her way into the just-forming group. “John [Phillips] had a definite idea of what he wanted—a group like the folk group Peter, Paul and Mary. My mom didn’t fit that [sleek] female look,” Owen says. But her talent and perseverance won out. John later changed the group’s name from the New Journeymen to (with Cass’s help) the hipper and wittier The Mamas and The Papas, cementing its charisma.

“My mother was The Little Engine That Could,” Owen says. “Weight shaming was something she dealt with all her life. She was constantly insulted and hurt by people calling or thinking her fat. But she never talked about her pain, and when she performed, she hid that pain. But I know—I could tell—that it bothered her. As a child she was teased as a fatty. Her weight was something she bore the scars of for the rest of her life, be it failed auditions for Broadway shows or lonely nights after The Mamas and The Papas’ performances at Carnegie Hall or the Hollywood Bowl, coming home alone when everyone else had a partner.”

Wrestling with Weight

Owen, too, is sensitive about weight consciousness. “I’m 30 to 40 pounds overweight, and I know there’s no quick fix.” When I dined with her back in 2006, in preparation for doing this Vanity Fair story on Michelle Phillips, she looked great to me. Owen has also watched her best friend and “soul sister” Carnie Wilson—of the trio Wilson Phillips (which includes Michelle Phillips’s daughter Chynna Phillips)—wrestle with her weight and take steps like bypass surgery. Even though attitudes are much more evolved today, in real life, Owen says, rather than This Is Us, “it’s still hard to be overweight.”

At 25, Cass knew she wanted to be a solo mother—a bold choice at the time, even in bohemian circles. “She wanted me more than anything else in the world—she told people that,” Owen says. “I was conceived in the summer of 1966.” Even though she was a musical star in the new moment of music media gossip, Cass successfully kept secret not only her pregnancy (ironically, her obesity helped in that regard), but the identity of the father of her baby—then and for decades.

Owen was born in April 1967, and “even the name she chose for me underscored her desire for a creature to love. She named me Owen because I was her ‘own.’ She called me Owenski. I’d sit on her big bed and watch football games with her; she had crushes on the players. ‘Look at that cute tush,’ she’d say. Motherhood filled her. She recorded a song called ‘Lady Love’ about its saving grace. In its opening lines she says,’This is dedicated to my baby daughter.'” In that song she sings of how she can make it through a lot of difficulties as long as “I have my little someone to hold onto … a little girl to set me free. … She came along just in time / in time to ease my worried mind / and now I’ve got a little someone to hold on to.”

Cass successfully kept secret not only her pregnancy, but the identity of the father of her baby—then and for decades.

When she was touring with The Mamas and The Papas, and especially after the group broke up in 1968 and Cass became a solo act, her single-mother life was stressful. “She was responsible for one hundred percent of my welfare,” Owen says. “She had to leave me with governesses, and it hurt her feelings when I would become attached to them. One nanny actually stopped working for my mom because she knew my mom was hurt that I was responding more to the nanny than to her.”

Though fans at the time loved Cass, Owen recently looked at videos of her old variety show appearances, and “I cringe in pain when I see the supposedly good-natured overweight `jokes’” that her mother had to endure, trying to be a good sport by laughing along. In truth, “She would go on starvation diets—she would drink only water for five days and then have steak for two days. She told Esquire magazine that she’d gone from 250 pounds down to a 170. One ramification of losing all that weight so fast is you lose muscle mass.” That can be dangerous.

Read More:`Killing Me Softly’ Brings Roberta Flack and Lori Lieberman Together At Last

The Ravages of Dieting

As a result of her crash dieting and intense schedule, in April of 1974, Cass collapsed on the set of Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show, just before she was to go on. She was treated in the hospital and dearly hoped it wouldn’t affect her career. She had to keep going; there were songs in her and money that needed to be earned. Three months later she played the London Palladium. Headlining—with two shows a night—that prestigious venue felt like a make-or-break moment because the house was not sold out during the first nights, and she had an uphill climb to get good word of mouth and wow them. And wow them, she did.

On her last night at the Palladium, on July 28, she got a standing ovation; it felt like a comeback. Immediately after the performance she wrote a rapturous letter to her seven-year-old daughter, telling her how much she missed her, and then she called Michelle Phillips in L.A. to share the triumph with the person to whom she had given so much confidence. Michelle said Cass sounded “elated.” Later that night, she attended a big party hosted by Mick Jagger and had trouble falling asleep afterward.

It struck me: I’d better get used to my new life. I don’t have my mother any more.

The next day, in her hotel suite, she had a massive heart attack. The lack of the muscle mass around the fatty tissue near her heart—an offshoot of her crash dieting—had contributed.

The Laurel Canyon world and her legions of fans were in mournful shock—she was only 32 years old.

“I remember sitting at my grandmother’s dining room table,” Owen says, “and her telling me, ‘Your mother’s not coming home.’ I remember just standing up and leaving the table and not understanding what had happened. I have had a lot of cognitive behavioral therapy over the years, and I know how denial protects a child.” The plan was for Owen to live with Cass’s younger sister, Leah, who was married at the time to James Taylor’s and Joni Mitchell’s drummer, Russ Kunkel, and had a son, Nathaniel, age three.

“It was after my mom’s funeral”—at Los Angeles’s Mt. Sinai Memorial Park, where many stars are buried—“that it hit me, dramatically. I was being asked who I wanted to ride home with, my grandmother or my aunt and uncle. It struck me: I’d better get used to my new life. I don’t have my mother any more. It was a hugely defining, hugely sad moment of realization.”

Read More: 3 Reasons Why Joni Mitchell Matters So Much to Us

The Father Question

After her aunt Leah got divorced, she took Owen and Nathaniel away from the Hollywood canyons and to the more traditional and academic Northampton, Massachusetts, where Owen lived for much of her childhood. “It was kind of a Norman Rockwell world,” she says. But one of the un-Rockwellian issues she faced was wondering: “Who is my father? Who is my father?” No one seemed to know. Cass had kept that an airtight secret, probably expecting to tell her daughter at some appropriate time.

Owen went back to L.A. after graduating high school on the East Coast, the question of “Who is my father?” still pulsing within her. On the night of her 19th birthday she was taken out to dinner by the members of her late mother’s group: Michelle, John, and Denny. There, at a popular Japanese restaurant atop the Sunset Strip, overlooking the twinkling lights of L.A., Michelle said, “It’s a shame we never did find out who Owen’s father was.” At which point Denny and John gave each other funny looks that seemed to say: You didn’t know that we know who he is? The two men had kept the secret for 20 years.

Owen went back to L.A. after graduating high school on the East Coast, the question of “Who is my father?” still pulsing within her.

His name was Chuck Day, they revealed, and he was a bass player in the band. “Denny probably said it,” Owen reports. Michelle came up with a sneaky plan to find him: She had her assistant place an ad in Musician magazine looking for “Chuck Day,” implying there were musical royalties awaiting him somewhere. “It was definitely baited” for him to surface, Owen says, with a grateful laugh.

A friend of Day’s called the number, the true reason for the ad was given, and a meeting was set up between Owen and her father, who lived in the Bay Area. Michelle bought Owen a ticket to San Francisco. “He was Swedish and Scottish” and not in the greatest shape, she reports of her father (now deceased). The meeting was “awkward but emotional. I remember feeling overwhelmed about how much this guy loved me, but he really was a stranger. I also didn’t need a dad—Russ [Kunkel] had been my dad from early on; he had gotten me braces and done all those father things.”

Owen concluded that it was the right thing for her mother to have raised her alone. Just as it was right for her to insist on the success that was due her talent, despite the fat-shaming that was in the air she’d breathed all her life but rose above.

“I’m proud to be my mother’s daughter,” says Owen, who, after a short singing career of her own, is now managing a new production deal for the re-release of The Mamas and The Papas’ music to preserve the group’s legacy for the children and grandchildren of all four members. “When I’m having a tough day, for whatever reason, I think of all the ‘you can’t be this; you can’t do thats’ that my mother heard but ignored or conquered. She was a hero to me.”

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

A version of this article was originally published in December 2018.

0 Comments