Editor’s note: Are you a single empty nester? We’d love to hear your experience in the comments!

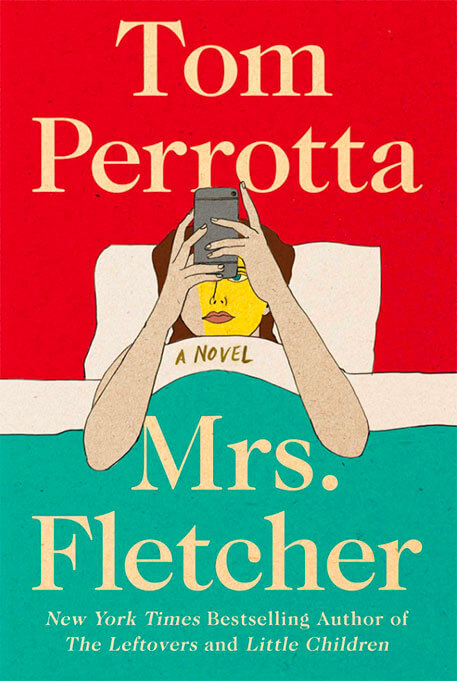

I was, as my teenage son would say, amped to read Tom Perrotta’s new novel, Mrs. Fletcher. For one, Perrotta is a master of the funny, engaging, quirkily sexy page-turner about modern life. (Think Little Children, his hilarious and heartbreaking 2004 adultery novel–cum-movie-starring Kate Winslet.) For another, I knew this book featured a middle-aged, newly empty-nest working mother—right up my alley, other than she’s divorced and I’m not. I wanted to see if Perrotta, mid-fifties-ish (also like me), nailed this female character, Eve Fletcher—the Mrs. Fletcher of the title—as he so brilliantly did, say, Sarah in Little Children, a bored (but never boring), unhappily married young mother who falls for a stay-at-home father at the playground.

I knew this book featured a middle-aged, newly empty-nest working mother—right up my alley.

Eve, a 46-year-old, kind-hearted if naïve mother whose husband left her years ago for another woman, is the executive director of the local Senior Center. She’s also the boss of Amanda, 26, the “short and buxom,” luridly tattooed, equally good-natured new events coordinator at the Center. Both women are lonely—Amanda because she’s recently out of a relationship and now living in her deceased mother’s suburban house; Eve because, after dropping her only child, Brendan, at college in the book’s early pages, she too is now single and alone in the ’burbs, poised somewhere between sexuality (she’s still attractive—a “MILF,” in fact) and the crumbling old age of her daily charges at the Center.

Both women are looking for love, or at least sex, where most people do now: online. Eve also embarks on a local community college class, called “Gender and Society,” as a way to “reconnect with her collegiate self, which had been so much more open and fluid and hopeful than the versions that had succeeded it.” Her fellow students (and teacher) turn out to be a lively mix of ages, genders, races, and political types—all the better to lead Eve to moral challenges and sexual awakening.

Both women are looking for love, or at least sex, where most people do now: online. Eve also embarks on a local community college class, called “Gender and Society,” as a way to “reconnect with her collegiate self, which had been so much more open and fluid and hopeful than the versions that had succeeded it.” Her fellow students (and teacher) turn out to be a lively mix of ages, genders, races, and political types—all the better to lead Eve to moral challenges and sexual awakening.

A chunk of the book’s (subtle but entertaining) plot has to do with the shrinking and eventual closing of teenage Brendan’s previously admiring world, even as his midlife mother’s world opens and expands—sometimes, with both characters, potentially dangerously. Brendan is a former popular high school jock who soon finds that his brand of entitled, clueless charm—possibly enhanced by watching too much online porn—doesn’t quite cut it in college.

The plot focuses on the shrinking and eventual closing of teenage Brendan’s world, even as his midlife mother’s world expands.

As the book opens, hung over from a final night out with his friends and struggling blearily to open an ibuprofen bottle while Eve loads his stuff into the car, Brendan is about to leave for that college, though not before receiving a last “gift” from his recently dumped (by text) high school girlfriend—a gift Eve has the horror of hearing from outside his bedroom door, in the form of the words, “Suck it, bitch!”

Brendan is a dolt for sure. But he’s also, in an odd way, sympathetic—in all his obnoxiousness, he really doesn’t get some important things about adult life today—and his sections offer a perfect and often hilarious glimpse into a certain type of modern teenage boy as he runs up against the intersection of high school prom king jock-dom with the more enlightened, sometimes aggressively sensitive culture that currently permeates college campuses.

In contrast, Eve and Amanda, despite their various sexcapades (Amanda likes emotionally uninvolved sex with older men she meets online; Eve surprises herself by developing a habit that I’ll just say, to avoid spoilers, she’s ashamed of), both, as characters, sometimes felt a little tame (or uninspired) to me. “It’s hard being a caregiver,” Eve says, in a typical line of dialogue when she’s at work, or, “We all did the best we could.” It’s true her job requires this sort of faux sensitivity and cliché, but this kind of thinking—and talk—often expands into her out-of-work life too: making small talk in a bar, say, or advising her friends. Sometimes I wished she were a little less of a goody-goody, at least in her mind; a little more edgy or angry or unusual.

Plenty will relate to the loneliness of empty-nest midlife when you’re too young to give up the hope of a little love—not to mention a little action—but not quite sure how or where to get it.

I almost hesitate to say that, because I realize it might say more about me (and not in a flattering way!) than about this character. But what I love about Perrotta’s writing at its most brilliant is that he’s able to make the lives of “normal” or even aberrant people seem complicated, interesting, and funny: a retired bully of a cop, a not-so-smart aging college athlete, even a sex offender. In fact, he’s often at his sharpest and wittiest when poking fun at a certain type of clueless, revved-up, athletic fraternity dude. In contrast, I didn’t feel his humor or writing prowess as acutely with these two women (except in the scenes where Brendan played a part). But many readers of Mrs. Fletcher will be gripped by Amanda and Eve. And plenty will relate to the loneliness of empty-nest midlife when you’re too young to give up the hope of a little love—not to mention a little action—but not quite sure how or where to get it.

Please watch editor Jeannie Ralston’s interview with reviewer Cathi Hanauer, co-creator of the Modern Love column in the New York Times.

There’s a wealth of up-to-date subject matter to think about in these pages. Internet sex is a big one, from hook-ups initiated online to porn and how it (maybe) influences teenagers to act. (Perrotta also broached Internet porn in Little Children.) How sex lives, and really all lives, for people of all ages, have changed with the advent of technology. There’s also parenting—of kids of various ages with various problems—and transformation of many kinds (another vivid character in the novel is a trans woman).

Add to that body image issues and sexism and sexual desire and the question of what, in the age of anything-goes Internet porn, is allowable in real life, and you’ve got a packed-full contemporary novel, offering up questions such as: Can a middle-aged woman accept the advances of an 18-year-old boy? Is it okay to sext someone a lewd (and anonymous) comment if it’s meant as a compliment? Should you indulge your sexual attraction for someone you know probably isn’t a nice person—or deny it and try to become attracted to someone who’s less of, in Brendan’s words, a douchebag? How do you navigate the line between desire and decency?

These are the dilemmas that make up Mrs. Fletcher, Perrotta’s seventh novel. As for whether they’re fully answered in the end, I’ll leave you with this quote from Chekhov: There is “the solution of a problem and the correct formulation of a problem. Only the second is required of the artist.”

A version of this article was originally published in September 2017.

0 Comments