I met Debbie Phillips, who is now 63, at a tea for her group Women on Fire about eight years ago. Given her group’s name, I was expecting the typical—now-ubiquitous—self-celebratory, we’re-all-winners “female empowerment” networking group. Instead I found an intimate table full of midlife women dealing with death, divorce, bankruptcy, new love, new jobs, and other life transitions. This was a helping group.

Debbie greeted each woman at that tea by taking her hand, looking her in the eye, and saying, softly, “Thank you for being here.” That earnest but completely un-hokey sincerity stuck with me. But when we became lunch-date friends, I saw her irreverence and humor as well as her generosity and enthusiasm.

Debbie is self-made; she created her own adulthood.

Like many great midlife women, Debbie is self-made. Raised in Ohio as the oldest of five children with poor and transient (the family moved six times in six years), but highly encouraging parents, Debbie created her own adulthood. She went from being a governor’s press secretary to a life coach to the founder of her now-mega support group that helps and inspires women all over the country.

The First Spark

Debbie had an unfulfilling first marriage, and a little over 20 years ago, six years after her divorce, she met Rob Berkley, a half-Jewish, half-African American executive coach who grew up in Brooklyn and Woodstock, NY. Rob and Debbie’s meeting came over the phone, via a group conference call. They made a date to continue the talk, a deux, in person; after developing a friendship, they fell in love, married, and made a pact that, as a couple, they would be “devoted to helping people express their gifts, strengths, and talents.”

Writer Phoebe Lapine described Rob as being “a friend, mentor, a father figure, a sage, a conspirator. He was infinitely optimistic, but also knew the power of a perfectly chosen expletive. He knew that being manly”—Rob was an amateur soccer star—“meant making sure that all the women around him were fully standing in their power. He found the perfect balance between living life for himself and supporting others fiercely.”

As a couple, they were devoted to helping people express their talents.

People loved Debbie and Rob for their dynamism, wit, and emotional generosity. When Rob died this past December 17, at age 59, after a year-and-a-half fight against gastric cancer, Facebook was flooded with heartfelt condolences. Debbie posted that, in honor of Rob, she hoped all their friends would have an interaction with someone that caused that person’s day to end better than it started. Only Debbie could say that and make it sound sincere, not sappy.

Emotional Elegance

Ten days after Rob died, I talked to Debbie about those last 15 months. Despite her grief, she was eager to talk—to celebrate Rob, to make sense of it all, to impart a few life lessons. The vast majority of us won’t need these now, thank God. But it’s inspiring to see how two people can insist on emotional elegance, creative grit, and productive optimism—and realism—despite the worst. Maybe we can use a little of their big lessons for our smaller challenges.

Make a plan together to make sure you don’t get overwhelmed and you stay close to what matters.

Right after Rob was diagnosed—in September 2017—with this most lethal form of cancer, “we sat down with our therapist, the brilliant and wise Norman Shub, to help us craft our plan for helping with clients, family, ourselves,” Debbie says. “He told us that, because our circle of people was so large, if we constantly retold the story about Rob’s cancer we could develop PTSD. He urged us to set boundaries and limit that talk. He helped us tremendously in those early weeks.” Then, shortly after those helpful sessions, “Norman himself was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died two weeks later. It was devastating.”

We were going to help him heal and make it an adventure.

Picking themselves up from that tragedy, “Rob and I made a vow: We were going to do everything to help him heal and make it an adventure and keep our lives as normal as possible.” High bar, that. They moved to Boston, where he was getting treated at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. “We explored the city every day,” she recalls, “and we got an apartment where we could see the games at Fenway Park out our window.”

Keep a sense of gratitude, as hard as that may be, and insist on a project with a future.

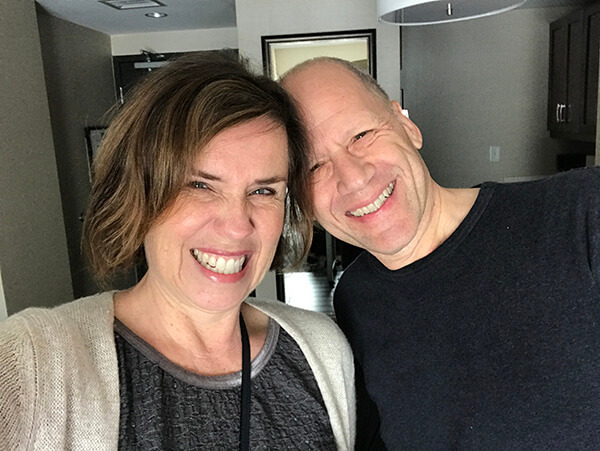

Debbie and Rob leaving the hotel for his first cancer procedure, full of hope that they could beat this.

In April 2018, Debbie sat in the hospital waiting room, “super, super hopeful.” If the surgeons could get all Rob’s malignancy out (something this optimistic woman felt sure of), the surgery would last a full eight hours. Debbie watched the monitors and counted the time as it marched very slowly. Two hours, three hours, four hours. All was good. Then the monitor stopped. The surgeon appeared. “I’m really, really sorry,” he told Debbie. “We found cancer in his stomach lining.” Then: “There’s nothing more we can do.”

Back at home, she says, “Rob and I sat on the couch, sobbing. Then Rob said, ‘I will not yield.'” This cued her to respond in kind. But how do you “not yield” with a terminal illness?

First off, Debbie was determined to do everything she could to stay in the moment with Rob. “We made physical care into acts of intimacy. I gave him his shots. I would shower him, I would dress him—things he would normally never allow me to do.” They made them sensual. “Patience and compassion and the most intense intimacy just developed naturally. We had to do this together.”

Each of us wrote down what we felt gratitude about—the tiniest thing.

As Rob was trying experimental treatment and palliative chemotherapy and receiving regular visits from nurses as part of hospice care, he was weakening. By last July he didn’t have the strength to bring Debbie her morning coffee, a marriage-long custom. Soon he was too weak to give her a full-body hug. “He cried when he said, ‘I can’t hold you anymore.'”

It helped this very masculine man to admit his vulnerability, and it helped others when he gave a speech to Debbie’s Women on Fire. “I love being with powerful women!” he raved to the group, before making a joke about his looks: “I’m 20 pounds thinner—but you don’t want to lose the weight like I did.” Then he gave a life-coaching lesson that included the merit of asking for help. “What keeps us all from asking for help?” Rob asked. “Fear and shame. I learned this. With cancer, you have fear and shame every day. But I got over it.” A rock is lifted when you get over both, he said.

The couple developed a routine they called “Grati Pads.” Every night before they went to sleep, Debbie and Rob whipped out pad and pen and, “each of us wrote down what we felt gratitude about. The tiniest thing. ‘A good glass of grape juice.’ ‘Holding you.'” And Rob insisted on a project with a future end-date: finishing a coffee table photo book on birds he’d been working on. He completed the coffee table book a month before he died. When he finished he said, “Honey, I need a new project!” Debbie could not disagree: Believing in continuing was important. The couple came up with a new plan to post Rob’s wisdom from unpublished blog pieces he’d written. “We had extra motivation because of our clients. When you’re coaching people to have better lives and careers, they look to you. You can’t disappoint them.”

Keep the humor alive.

Along the way, even at the end, Rob showed his sense of humor. For example, Debbie ate comfort food for months on end, and “one day I overheard him tell the nurse, ‘In her next chapter, she’ll go back to eating salads.'”

Thinking of the funny parts, even the eye-roll-worthy stubborn-male parts, can be cathartic. So Debbie is doing that now. “It’s my worst grief day yet,” she says, “but [remembering the laughs] is making me feel better.”

Remembering the laughs makes me feel better.

Before Rob died, the question of how Debbie would continue on without him lingered in the air. “I waited for Rob to give me ‘permission’ for a future without him. But he didn’t. The hospice people told me that husbands often don’t like thinking of their wife with someone else. Whereas women often say, ‘Oh, honey, find a great woman and be happy again.’ Just before he died, Rob said, ‘You’ll have lots of dates in the future, so be sure to find a great companion and travel with him … but with separate beds.’ Separate beds: He was serious! That cracked me up!”

When Debbie recounted this story at a gathering a few days after his death, somehow it got howls of laughter.

Clear the air and keep the warmth at the end.

“The Monday before Rob died, his hospice nurse took his hand and said these beautiful words: ‘You are struggling so hard. You’re living on sheer will. We know you don’t want to go, but you have no reserves left. In the end nature always wins. It always wins.'”

Rob asked, “How does this go now?” She said, “We just keep you comfortable.” Then Rob asked Debbie, “Is there anything you need to talk to me about? Do you need my forgiveness for anything?” She told him there was nothing. “We had worked all that out in the months and months we grieved together,” Debbie says.

“The night before he died, I was up all night with him. He said, ‘My time is short.’ I held him, and we cried. He was declining but he was conscious. I felt tethered to him. I stayed with him for hours. I thought we had a little more time, so I walked downstairs to get a cup of water. He died when I walked back into the room. I got back in bed and lay with him. I stayed and watched the sunrise. It wasn’t at all creepy. It was beautiful and powerful and incredible. You’re supposed to be cold when you die but, amazingly, for hours Rob stayed warm.”

Life coaches teach that people make their own fates and futures. Still, sometimes, miracles happen.

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

0 Comments