It’s not uncommon for women to engage in the act of reinventing themselves as they get older, when life’s circumstances demand that they roll with the punches. But Gerty Simon is a different case altogether; the catalysts for her journey were a toxic political climate and the threat of death.

Gerty Simon made a do-or-die reinvention. We want to hear about your own reinvention—maybe with lower stakes, maybe not—in our Reinvention Essay Contest. Deadline July 18th. Details here.

Simon’s work can be seen in an online collection of the Weiner Library called “Berlin/London: The Lost Photographs of Gerty Simon.” The Wiener Library, the world’s oldest collector of material from this era, received a gift of over 350 of Simon’s prints. After Gerty’s son died in 2015, the art was donated by his partner, along with personal documentation. Many were originals from the 1930s. All the glass-plate negatives had been destroyed.

The exhibit not only brings to light the life of this exceptional photographer, but also documents Gerty’s vision at a pivotal moment in German history. A catalogue with essays by Dr. Barbara Warnock, senior curator at The Wiener Library, and researcher John March, helped to fill in some of the story of Gerty’s life. NextTribe also learned more directly from Warnock.

Gerty Simon Self Portrait Montage

Gerty (born Gertrud) was born in 1887 in Bremen, Germany, to a family of assimilated Jews. At the age of 32, she married Wilhelm Simon, whose background was similar to her own. Having studied law, by age 27, Wilhelm had become an assistant judge in Strasbourg. During World War I, he enlisted in the Germany army, and was awarded an Iron Cross for his service. The couple moved to Berlin in 1919, and two years later, Gerty gave birth to her son, Bernard. Not long afterward, in 1922, photographs taken by Gerty—who has been described as self-taught—began appearing in the German press.

Read More: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché, the Mother of Cinema

Life in Weimar Berlin

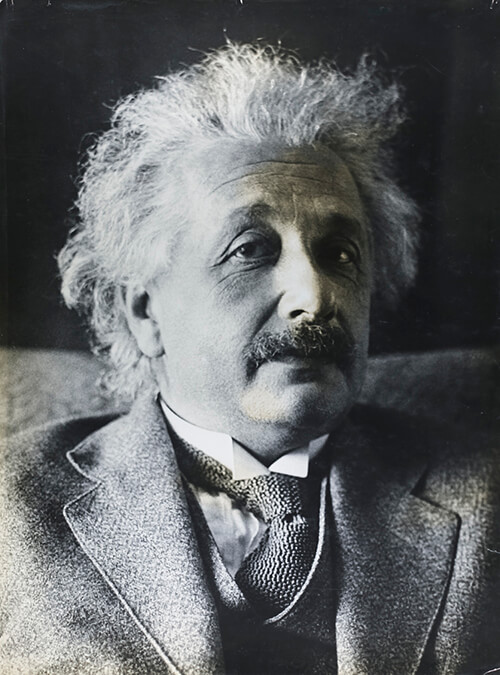

Albert Einstein (1879-1955), Berlin, c. 1929

Artists are formed by the era and milieu in which they live, and Weimar Berlin was the backdrop for Gerty’s development as a photographer. She took studio portraits of the creative luminaries of the late 1920s and early 1930s—actors, artists, writers, composers, and dancers who were part of the avant-garde elite. She also knew leading intellectuals, activists, and those in the political realm. Käthe Kollwitz and Albert Einstein were some of the well-known subjects captured by her lens.

“Gerty Simon’s work is steeped in the modern cultural developments of Weimar Germany,” Warnock explains. “It seems that both her professional and personal life were spent with people of great creative influence and talent. This is reflected in her portraits of those who were representatives of the artistic flourishing of Weimar Germany. These individuals, along with the Social Democratic politicians, were the first to flee Nazi Germany. Often they were forced into exile.” Many had their work denounced as Degenerate Art. Renée Sintenis, who sat for Gerty, was one of the artists included in the 1937 exhibition of such artwork, which was seized from museums because it was not in sync with the aesthetic and national ideals that National Socialism was cultivating.

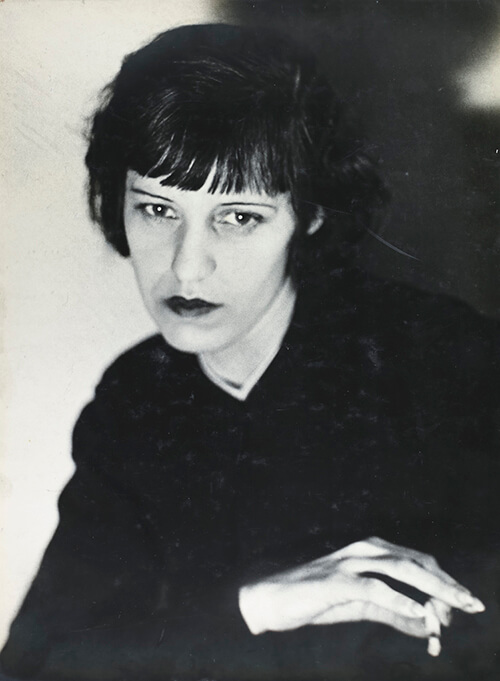

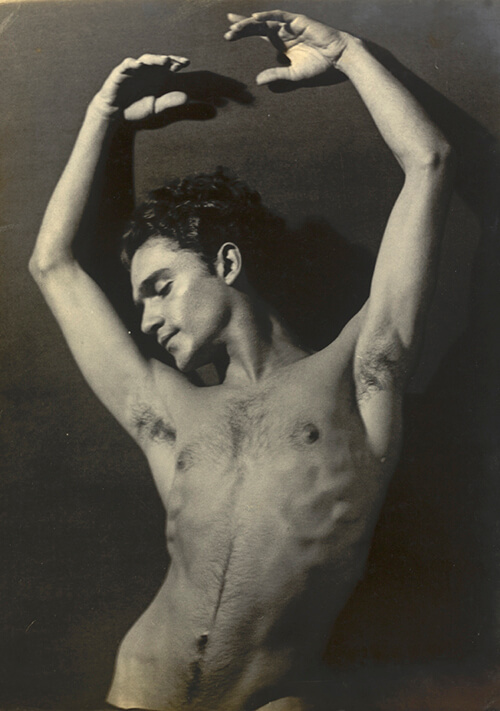

Tatiana Barbakoff (1899-1944), Berlin c. 1925-1932. Ballet & Chinese dancer

As Nazism rose, not everyone would survive the killing storm, not even the esteemed artists Gerty often photographed. Indeed, her photograph of Tatiana Barbakoff, a Jewish ballerina of mixed Russian and Chinese heritage, would stand as a testament to the dancer murdered in Auschwitz in 1944.

“In the late 1920s, up until she left Germany in 1933,” says Warnock, “Gerty contributed editorial photographs to the leading journals of the time.” She was also referenced as prolific and prominent in her field of portraiture. Her work was included in a major 1929 international exhibit of contemporary photography, Fotografie der Gegenwart. That same year, Gerty had a solo show, “Spirit of Berlin—Spirit of Paris” in Berlin. She combined images of public figures from both capitals, including a shot of the author Colette in profile. It received wide press coverage and acclaim in an era when women were not commonly seen behind the camera.

Sensing Danger

Jena glass worker and his family, c. 1925-1932

By 1933, Gerty grasped the trajectory of the Nazi party. Her son’s progressive school, run by a noted Jewish educator, chose to relocate to England, recognizing the changing guidelines that would be enforced. This greatly impacted Gerty, who also decided to leave her homeland, although she was powerless to secure either her money or property.

In a restitution claim written in the 1950s, Warnock reveals that Gerty wrote about why she felt compelled to leave Germany: “… under the Nazi regime I found myself as a Jew in particular danger, because as a photographer, I had taken numerous photographs of Social Democratic and anti-fascist personalities and exhibited them in public.”

Gerty and her adolescent son resettled in England, but her husband had no luck in acquiring the necessary paperwork to leave.

Read More: Need Creative Inspiration? Then You Need to Know About 88-Year-Old Artist Faith Ringgold

Starting Over

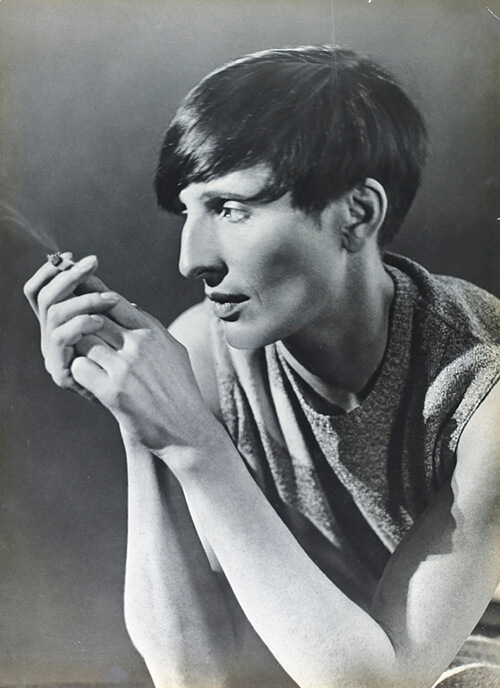

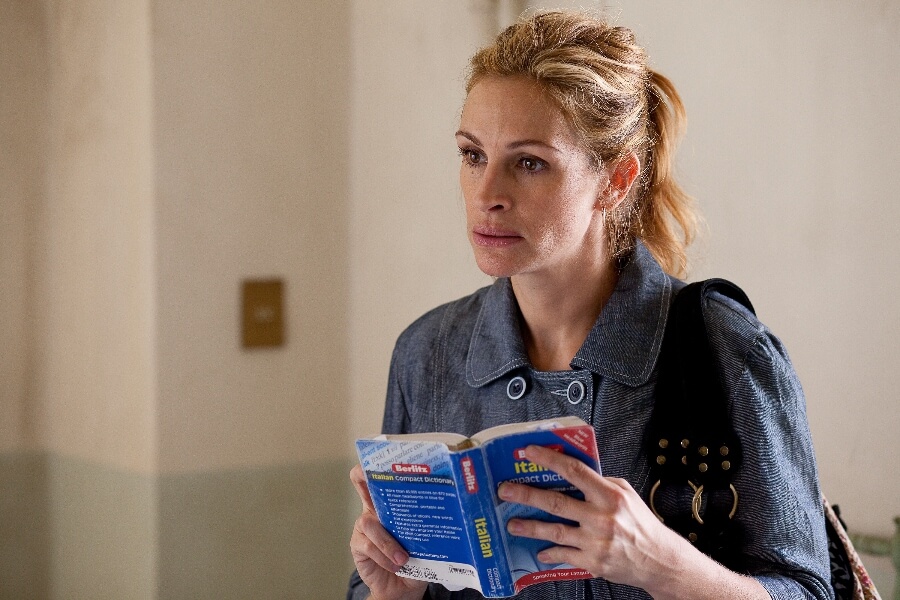

Lotte Lenya (1898-1985), London, c. 1935. Singer and actress

It was undoubtedly a stressful time as the international political scene shifted. Nevertheless, Gerty re-established her practice in London. Within two years, her studio was busy as she captured images of the top echelons of British society and the arts. Her work was seen in two exhibits, and her accomplishments were widely written about and praised. Many of her subjects included fellow refugees like her friend, the actress Lotte Lenya.

“Gerty’s astonishingly quick success in London suggests that her reputation preceded her,” Warnock says. “Regardless, it is a testament to her strength of personality, her energy and tenacity.”

In November 1934, Gerty presented her first show in Kensington entitled, “London Personalities.” The Sunday Times characterized her as the “most brilliant and original of Berlin photographers.”

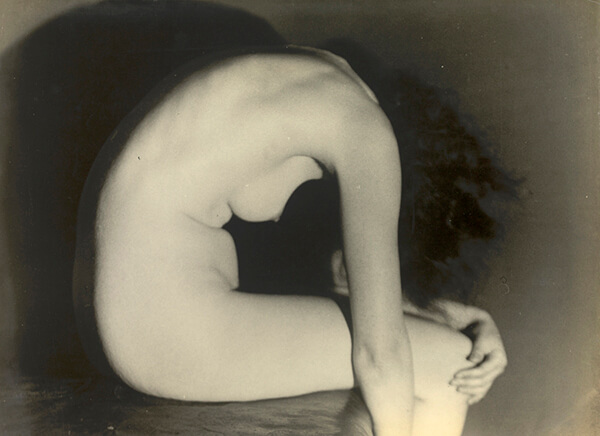

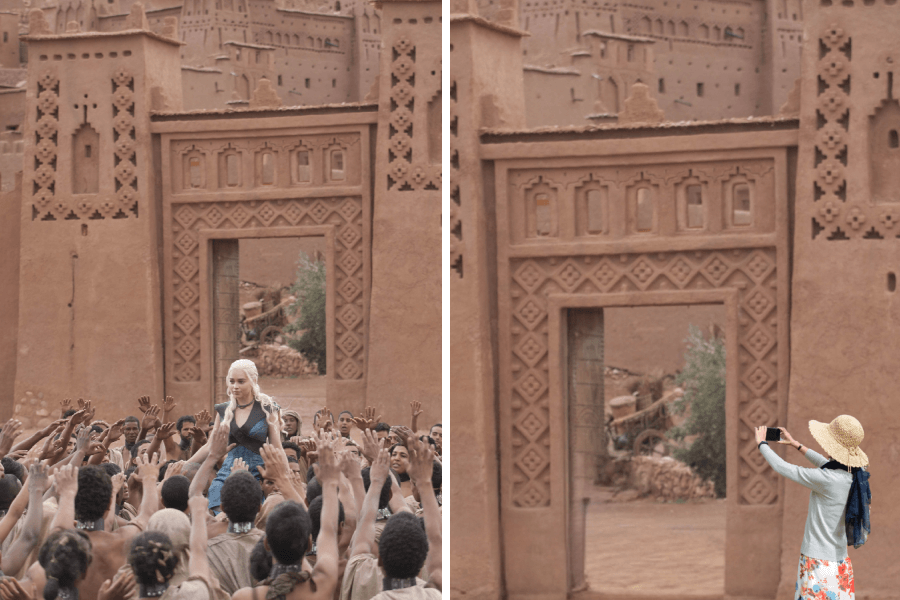

Gerty’s portraits were known for their honesty. There was no retouching, as her goal was to reveal the essential character of her subject. She used camera angles innovatively, as well as illumination to yield a sculptural aspect. Her “Unknown Subject” nude presents the female body as an abstracted form, rather than as an erotic object to be observed by the traditional “male gaze.” Gerty also demonstrated her creativity and originality in her self-portrait montage, using double exposures to comment on aspects of her identity.

Warnock pointed to the use of “dramatic light and shade” in Gerty’s photographs, and the “expressiveness that makes the work very striking and unforgettable.” Gerty’s philosophy in her work was that “in portraiture … everything depends on capturing the essence of a person … feeling is everything.”

Renée Sintenis (1888-1965), Berlin, c. 1929-1932. Sculptor and medalist

There was also a subtext in many of her photographs. In a double portrait of two young Weimar women, for instance, the composition suggests an unspoken intimacy; the relationship hints at the active gay culture of Berlin. Similarly, the photo of Renée Sintenis embodies an aura of fluid sexuality that would be easily identifiable today. “It might be inferred from looking at Gerty’s extensive portraiture that there was a sympathetic attitude towards homosexuality,” said Warnock. “Several of the images of women are very androgynous/masculine.”

A Disappearance and Rediscovery

Unknown nude subject, likely taken in Berlin, c. 1925-1932

Gerty’s work earned acclaim over the years, but changes were afoot. Though no one knows why, Gerty seems to have stopped taking pictures around 1937. The family then navigated intense ups and downs: After the violence of the 1938 Kristallnacht attacks on German Jews, Wilhelm obtained a sponsored visa and escaped to London, rejoining his family. But in 1940, both husband and son were arrested and interned as German aliens. Bernard was shipped to a camp in Australia with 2,000 other young men, most of whom were Jewish. Wilhelm was transported to the Isle of Man. It was ironic that in the nation where they found asylum, the family faced a forced separation and detention for the father and son.

By 1941, the family was finally reunited and living near Wimbledon. All members of the clan became naturalized British citizens by 1948. Wilhelm died in 1966; Gerty in 1970.

The Legacy of Her Lens

Alexander Iolas (1907-1987), c. 1925-1933. Ballet dancer, later a gallerist

Gerty’s work might well have been largely forgotten if not for the gift of her work to the Wiener Library. The exhibition became an opportunity to rediscover her work and unearth the names of some of her sitters. Approximately 70 of the portraits had unknown subjects. Before the exhibit opened, the Wiener Library launched a social media campaign called #FindingGerty, asking for the public’s help discovering the identities of individuals. The Library was contacted by people from around the globe, and several subjects of Gerty’s portraits were recognized.

One was Alexander Iolas, a Greek ballet dancer who came to study in Berlin, but fled Germany for Paris when the Nazis came to power. He later became a prominent European and American art collector and gallery owner, dubbed “the man who discovered Warhol.”

Gerty’s photographs have a lasting impact. Says Warnock of the portraits, “This collection of powerful and intense photographs is a part of, and a valuable record of the individuals who contributed so much to the culture of the lost world of Weimar.” After eight decades, Gerty’s photography are reviving that era—and her own fascinating legacy.

All photos: © The Bernard Simon Estate, Wiener Library Collections

A version of this article was originally published in July 2019.

***

Marcia G. Yerman, based in New York City, writes profiles, interviews, essays, and articles focusing on women’s issues, human rights, the environment, politics, culture and the arts. Her work has been published by the New York Times, truthout, AlterNet, The Raw Story, Women News Network, and The Women’s Media Center. Her articles are archived at mgyerman.com. You can find her on Twitter @mgyerman.

0 Comments