Read time: 7 minutes

The poet and peace advocate Naomi Shihab Nye resides in San Antonio, Texas, but she also lives on the road and in the air, constantly traveling to read, teach, and talk with people all over the world. This wandering lifestyle doesn’t stop her from getting a little writing done: Her Wikipedia page lists 12 books of poetry (one a finalist for the National Book Award), three novels, and three books of short stories. In addition, I own at least two books that aren’t even listed—Never in a Hurry, a collection of essays, and Mint, a book of prose poems.

In the face of all the current forces that threaten to suck us in or keep us down or drive us to despair, these are poems of connection, celebration, and resistance.

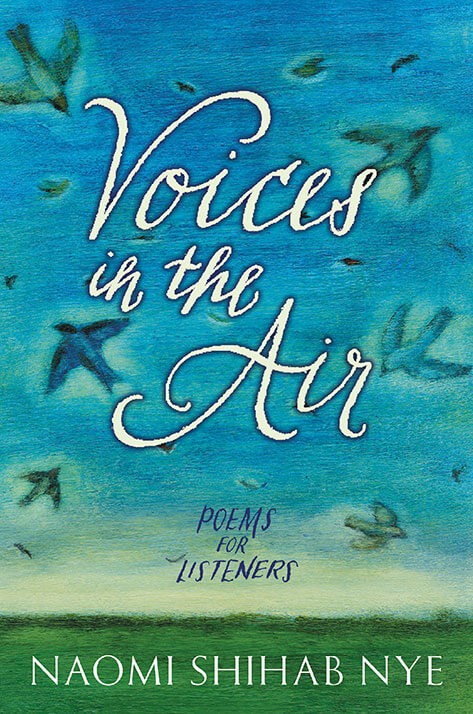

New this month is Voices in the Air, a collection of nearly 100 poems that are lively, straightforward, and easy to understand, bursting with strong opinions and useful advice. Many of the ideas in the book are inspired by the “voices in the air” of a large group of historical and cultural figures. All are identified in a wonderfully subjective and quirky biographical index at the back of the book: Jamyla Bolden, Jack Kerouac, John O’Donohue, Joni Mitchell, John Masefield, Jose Emilio Pacheco, Joanna Newsom, James Tate, Josephine Miles, John Steinbeck, and John Muir—those are just the Js! After talking to Naomi I realized that this index is included because the book is meant to be accessible to teen readers as well as adults, but I found it very exciting not to be expected to know everything, let alone remember it. I hope it is a trend.

If you have not made a habit of turning to poetry for inspiration, this book may change your ways. In the face of all the current forces that threaten to suck us in or keep us down or drive us to despair, these are poems of connection, celebration, and resistance. The author and I have been friends since we met at a women’s writing conference in 1980. But we live far apart and don’t see each other much, so it was a rare pleasure to spend half an hour on the phone talking about her new book. Here are some excerpts from that conversation.

A Conversation With Naomi Shihab Nye

MW: This book is dedicated to Connor James Nye and Virginia Duncan. Tell us who these people are.

If you have not made a habit of turning to poetry for inspiration, this book may change your ways.

NSN: Ah, Connor! Having a little grandson in our lives has really refreshed our spirits, and what a good time in our history to have one’s spirit refreshed. In this the downbeat, nasty political atmosphere, to have a joyous little person who knows nothing about any of that—it’s like a cool wind blowing through the room.

MW: I believe there are a couple of poems that address Connor directly: “I Vote for You,” and “To Babies,” which reads, “May polar bears welcome you / to Northern Manitoba, their lumbering grace / marking the ice. May there still be ice. May giant trees lean over your path / In warm places, brush your brow.”

NSN: Yes, that’s him! And Virginia Duncan is my longtime editor at Greenwillow, for almost 30 years now. She reached out to me years ago to ask if I had thought of doing anything for young readers, and now we’ve done tons of books together. It’s one of the enduring relationships of my life. Connor and Virginia don’t know each other, but both of them sustain me in these times.

MW: Wait—is “Voices in the Air” a book for young readers? I thought it was for stressed out, middle-aged women! Even the nice large type—I thought it was so we don’t have to wear reading glasses.

MW: Wait—is “Voices in the Air” a book for young readers? I thought it was for stressed out, middle-aged women! Even the nice large type—I thought it was so we don’t have to wear reading glasses.

NSN: That makes me so happy. Since Virginia and I did our first book together, This Same Sky, so many years ago, it’s been our secret dream that we would reach everyone from fifth grade on up. That book is still in print, used in middle schools, universities, given as gift to adult poetry lovers. No borders! No border walls!

MW: Okay, that’s another poem I love in this book: “Big Bend National Park Says No to All Walls.” “You will not find a prime minister in Big Bend / a president or even a candidate, beyond the lion, / the javelina, the eagle lighting on its nest.” Beautiful!

Throughout the book, in lines like “A peony has been trying to get through to you” and “Some people grew up receiving no messages at all,” you urge us to spend time away from our cell phones. Can you talk about why this is so important?

Everyone I know is always saying, `Why did I say I would do this?’ People are really good at putting that urgent responsibility on others.

NSN: I, too, am addicted to my phone, the news, checking messages, the virtual world, the clamor of continual feed, but I think we have to be more deliberate about taking time off. Setting out on that quiet walk, playing with a baby for hours, even reading a book—without checking messages, without answering calls, just having a pure experience, uncluttered, unfettered. It’s more of a luxury now. We have to make a deliberate commitment to stay in touch with the simpler tools of life, to maintain a simple, clarified consciousness. I’m not saying, only touch your laptop once a week, or only use pencils. I believe we need both.

MW: One of my favorite poems in the book is “Next Time Ask More Questions,” reprinted here. To me, this poem should be the motto of the stressed-out, overburdened women of the world.

NSN: Oh yes, we’re always helping everyone out. Everyone I know, women in my neighborhood, poetry colleagues, friends from afar, is always saying “How did I get into this? Why did I say I would do this?” I have the same problem, saying “Sure, I’ll help you,” and “I’ll help you, too” and then “Yes, of course”—and people are really good at putting that urgent responsibility on others, so you feel like you really should do all these things. I feel trauma when I can’t attend someone’s art opening, even if they’ve never come to a poetry reading of mine in their lives! We have to spare ourselves. The last piece of advice the poet William Stafford gave me was, “Just learn to say I can’t.” You don’t give a reason, because then they can argue. Just say “I wish I could be there but I’m sorry, I can’t.”

MW: I can see this poem posted over a million desks! Going up over mine right now!

Some lines in the book that really struck me were at the beginning of the “Voices in the Air” section: “People don’t pass away / They die / And then they stay.” I plan to use these as the epigraph of my own upcoming book, The Baltimore Book of the Dead. They pretty much sum up the point of the whole thing. I’ve always disliked the term “pass away” or “pass.”

NSN: Me too, even when I was a child. A breeze is something that passes away—but to say it of a person—oh, you little wisp, you’re gone now—it’s just wrong. I realized that people were trying to soften the seeming harshness of “he died” or “he’s dead.” But it’s false, and it’s almost an insult to the magic of life—you’re born, you live, you die. However, when you read a writer, even if they died a hundred years before you were born, and their words are transporting you, awakening you—they’re not dead! They’re still here. The whole concept of Voices in the Air arises out of that. In times of trouble, where can we turn? We can turn to the writers we love and the voices who have guided us through our lives.

In times of trouble, where can we turn? We can turn to the writers we love and the voices who have guided us through our lives.

You know, years ago when my father died, I remember calling you on a flip phone as I was driving away from the hospital in Dallas, crying, and you said, “Just wait, you will come to see that he lives on for you in so many ways you can’t even imagine right now.” As the years went by, I found out that you were so right. I’ve passed that thought on to so many people in their extreme initial grief. In fact one of them recently told me, “Gosh, I feel like I’m having a better relationship with my dad than I had when he was alive. Back then, he never had time for me at all and now—he can’t get away!”

MW: One last thing I wanted to discuss. Several of the poems mention Ferguson, Missouri, and Palestine, your two hometowns (and I want to point readers to an essay you wrote in the Washington Post, “On Growing Up in Ferguson and Palestine.”)

It was so weird to me that the two places of my life were in a state of trauma and disaster and injustice all at the same time.

NSN: My parents moved to Ferguson when I was two—it was a white community then—black people lived on the other side of an invisible line. And growing up I had so many questions about this, particularly as the child of the only Arab in town. Why? Why are we separated? Then violence erupted so many years later in this place that people never even heard of—and the same summer 500 people were massacred by the Israeli artillery force in Gaza—and it was so weird to me that the two places of my life were in a state of trauma and disaster and injustice all at the same time. Sometimes you just are thunderstruck by the strange connections in your life. I think that’s one of the things that made me be a writer. I was fascinated by strange connections, always.

MW: Ah yes, that piece in the book called “Unbelievable Things” is one of my favorites. One strange connection after another, and then these last lines: “We are here, so deeply here, and then we won’t be. And that is the most unbelievable thing of all.”

But as long as I am here, Naomi Shihab Nye will always be with me. And I hope with you, too. In the air, we will always hear her voice.

0 Comments