One of the most highly promoted TV series of the 2019 season was I Am The Night, which was “inspired” by the fascinating memoir One Day She’ll Darken by Fauna Hodel, a white woman who, as the infant daughter of a severely abused young incest victim of culture and privilege, was given up for adoption to a black cleaning woman and who grew up thinking she was black.

Only when she was 19 did Fauna learn not only that was she white, but also that she was the granddaughter of the unsurpassedly evil Dr. George Hodel, a noir-era Los Angeles gynecologist whose depravity is almost fiction-worthy, except it is true. George Hodel worshipped the Marquis de Sade, was best friends with surrealist artist Man Ray and director John Huston and was obsessed with incest. He was also, almost beyond a shadow of a doubt, the killer of Elizabeth Short, the young would-be actress known as the Black Dahlia. Take a gander at this book by his son, police detective Steve Hodel, who solved the murder. Dr Hodel was also likely the killer of two other women.

I know all of this because I had many conversations with the real Fauna, a former gallerist and motivational speaker who, in a tragedy so apt for this irony-strewn true story, died of cancer while this TV series inspired by her life was being made. Directed by feminist superstar Patty Jenkins (Wonder Woman; Monster), this series was what Fauna had long dreamed of seeing.

Sordid elements of this real-life family also inspired Roman Polanski’s Oscar-winning movie Chinatown.

The riveting six-part series I Am the Night is mainly based on Fauna Hodel’s search for her identity—racially and otherwise—and it incorporates an invented newspaper-reporter character played by Chris Pine who works with her to uncover the fact that Fauna’s grandfather was the Black Dahlia’s killer. Director Patty Jenkins was fascinated by Fauna’s particular story for years. After making a version of her story—starring Alfre Woodard—that never got released, Fauna and Jenkins stayed friends, and, as good filmmakers do, Jenkins zeroed in on Fauna and the invented reporter character to grippingly tell a broader story. (Sordid elements of this real-life family also inspired Roman Polanski’s Oscar-winning movie Chinatown.)

But, as in any show that is “inspired by,” much is omitted. In this case, two women are left out—one is alluded to in I Am The Night and perhaps briefly portrayed in an upcoming episode, but one is not mentioned at all. This horrible saga actually envelopes three women: Tamar, Dr. Hodel’s daughter; Fauna, Tamar’s first daughter; and FaunaElizabeth, Tamar’s second daughter. Yes, dear reader, two of these real-life women have the name: Fauna. But they are two different women–half-sisters. The poignant reason for the similar names will be explained momentarily.

I interviewed Tamar (who died three years ago), exclusively. I also interviewed FaunaElizabeth several years ago and again just now, in advance of her appearance in a TNT-affiliated podcast, which will start airing on February 13. FaunaElizabeth was named Deborah at birth, but for clarity’s sake, I will continue to refer to her by her long real name, FaunaElizabeth. The linked stories of the three women show the tragic intergenerational destructiveness of incest and abuse—but also how they can be survived.

A Homicidally Decadent Father

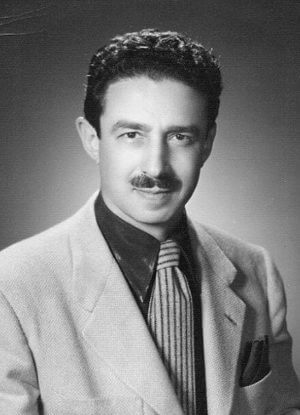

George Hodel. Image: @LelandsLegions/Twitter

Let’s go way back to 1946, the height of noir Hollywood: dark, duplicitous, sexy near-downtown Los Angeles, a simmering stew of sophistication, desperation, and veiled danger. Luminously talented people of urbane temperament commingled with Middle America beauties whose ambitions often stalled at the hatcheck-girl or diner-waitress stage; hard-boiled cops braved police and city hall scandals; and powerful men could be cruel, in at least one case using art to commit murder. This man was the brilliant Dr. George Hodel, a man of upper-class background and deep pathology—a genius-IQ former piano prodigy, now a gynecologist specializing in helping (and abusing and blackmailing) venereal disease patients and making payoffs to people who would keep him out of trouble. He was also the owner of a grand home in Hollywood that looked like a Mayan temple.

My father always said that sex between a father and a daughter was the most beautiful experience.

George had a daughter with one of his several wives, and he named her Tamar, because “Tamar” was the name of a girl in a poem by his friend, writer Robinson Jeffers (in the poem the girl has an affair with her brother).

When she was nine, Tamar was summoned down from San Francisco, where she’d lived with her mother and had attended elite private schools—to live with her father. “George was treated like God” by women, Tamar said when she spoke with me on the phone from her home in Hawaii 13 years ago. Almost immediately after her arrival, he started grooming her for sex. For instance, he had Man Ray take photographs of her naked. “It made me so uncomfortable,” Tamar told me. “My father always said that sex between a father and a daughter was the most beautiful experience.” Her high, prim voice seemed too tired and sad to evince anger. She wanted to tell her true story for the first time because it had been distorted in other accounts, she said, and it lay heavily in her heart—just how heavily I wouldn’t fully know until recently.

Sexually Serving “God”

George Hodel made his daughter Tamar perform oral sex on him when she was 11. “I was terrified and gagging—and I ran off and threw up. I was embarrassed that I `failed’ my father.” He persisted in “training” open her small mouth until she didn’t gag, and “he kept giving me these erotic books to read, and he told me that when I was 16 he would make me a woman. Of course, I wanted to `be a woman`! What girl doesn’t? I had no contact with the outside world. He kept me almost a prisoner.”

Tamar’s father didn’t wait until she was 16—he raped her when she was 14, and, to her shock and horror, she became pregnant. He ordered her to have his baby. When she told a friend about her pregnancy, the friend took a terrified Tamar into her house and arranged an abortion. After that “my father acted so strange and possessive! If kids from high school came over to see me, my father met them outside with a gun. And once he hit me with a gun!”

George Hodel’s new wife, Dorero (George coined the new name from her actual name Dolores plus Eros) told Tamar that George was dangerous. He had been guilty of watching (and perhaps abetting) the suicide, via overdose, of another woman. He would also turn out to be a prime suspect in the murder of Elizabeth Short, the actress known as the Black Dahlia, whose body was left in a downtown Los Angeles field in broad daylight, cut up almost exactly in the configuration of a famous painting of the surrealists, with whom George was so worshipfully close.

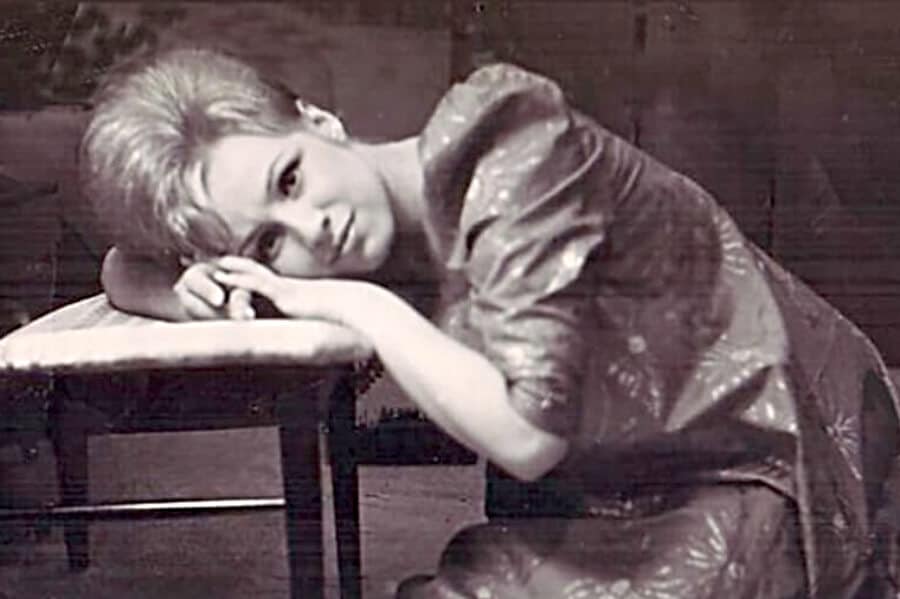

Fauna Hodel, whose book is the basis of the mini-series “I Am the Night.” Given away for adoption, she ended up being the lucky daughter of Tamar Hodel. Image: Elle Zober

After several months of enduring her father’s possessive brutality—this was 1949—Tamar got a warning from her stepmother. “Dorero told me to run away – right away!” Tamar told me in the phone interview that I typed, word for word, and which has been fresh in my mind as the series airs. “I called my friends from high school, and they hid me, and, because I was so afraid of my father and his power, they would move me from one location to a new location every two hours. I consider that I was lucky—Dorero saved my life.”

Determined to repossess his daughter, George Hodel put out a Missing Persons report on Tamar, and “in three days the police found me.” She was forced to tell the police about the incest, and in December 1949, George Hodel was put on trial. With fear, but compelled under oath, 14-year-old Tamar told the truth. But George’s high-priced Hollywood lawyers vehemently called the shaking Tamar a troubled liar who had multiple boyfriends—both were lies. Despite two witnesses who said they had seen George forcing sex on his very young daughter, the incesting father was promptly acquitted and the victim—Tamar—was eventually sent to juvenile hall. Yes, this happened! And in sophisticated, liberal Hollywood.

When Fauna learned at 19 that she was white, she was crushed.

In juvenile hall Tamar was raped by a local man and had a baby at age 15. She named the baby Fauna from the same Robinson Jeffers poem about incest that her father had drawn inspiration for her name. The baby’s father was also white, but George Hodel—still controlling his daughter’s life—placed the baby for adoption with an African American cleaning woman in Reno. This is the story the late Fauna Hodel told in her book One Day She’ll Darken and the one the mini-series focuses on. In I Am the Night, the complexity of feeling black but being suspected as white by her black peers is beautifully portrayed by actress India Eisley. When Fauna learned at 19 that she was white, she was crushed; she was so proud to “be” black, she told me three years ago.

She would not meet her biological mother, Tamar, until she was in her early 20s. Though her life with her adopted mother in Nevada was complex and challenged—racially, financially, and in other ways—she avoided the worst of growing up as the daughter of a woman as ruined as Tamar had been. That fate would be, sadly, lived out by Tamar’s second daughter.

The Tragedy Not Talked About

Tamar with her husband, Stan Wilson. Image: Courtesy of FaunaElizabeth Simon.

What the series I Am The Night doesn’t say is that Tamar had another baby, in 1954, with her husband, black jazz musician Stan Wilson. Avant garde and idealistic, Tamar wanted to live in the black world “because my father was white and he did such terrible things to me. I turned against white people. I trusted black people.” In a segregated time, it was bold to do so.

Tamar and Stan Wilson named their baby Deborah. Deborah’s middle name, Elizabeth, was given to her by George Hodel in “honor” of the murdered Black Dahlia, Elizabeth Short. Deborah later changed her name to FaunaElizabeth.

There are all kinds of wrong here: That Tamar’s father was still in her life, for one. But Tamar couldn’t help but want to please him, which can only be explained by his manipulation of her since she was a child. The wrong that most challenges incredulity is that George Hodel gave the baby the middle name after a murdered and dismembered woman—one he most likely murdered and dismembered. But FaunaElizabeth convincingly says it is the true origin of her middle name.

The Glamorous Woman in Lavender

In her 20s, Tamar Hodel tried to commit suicide several times. “I think, despite all her idealism and efforts, what George did to her drove her crazy,” says Michelle Phillips. Today Michelle’s name rings a bell as the former and forever-famous Mama Michelle in the Mamas & the Papas, but, at the time she met Tamar, Michelle was a beautiful 11-year-old Hollywood neighbor of Tamar’s. “She looked like a young Brigitte Bardot” is how Tamar described Michelle to me. Michelle had a strong and good father—Gil, a probation officer with bohemian leanings. But her mother had died when she was young. “I always looked for older girls, big sister and `mother’ figures,” Michelle say

The minute young Michelle met Tamar, who by then had her baby Deborah Elizabeth, she was fascinated. “Tamar was the epitome of glamour,” Michelle recalls. “She was someone who never got out of bed until two p.m., and she looked it. It was late afternoon, and she was dressed in a beautiful lavender suit with her hair in a beehive. She was so exotic! She was instantly my idol.”

But Michelle Phillips adds that, for all her glamour, Tamar in her early 20s, “didn’t have a friend in the world.” And, even as a tween, Michelle knew there was something very, very wrong with Tamar’s frequent insistence that it was a good thing to have sex with your father. “She kept saying,” Michelle told me by phone the other day, “`Oh, my mother and my father told me that this was the most beautiful way a girl could be introduced to sex—by her father.’ Even as an 11-year-old, I knew it was revolting! I felt so bad that she had a need to `normalize’ how her life had been ruined.”

Nonetheless, despite her desperate need to rationalize the pathology of her girlhood, Tamar took Michelle into her home and made a young sophisticate of her. With money Tamar may have gotten from George, or from her husband Stan, or from various other men (she would soon be adept at some informal versions of living off of male acquaintances), Tamar bought Michelle the clothes that Michelle’s father couldn’t afford, enrolled her in modeling school, taught her how to drive her lavender Nash Rambler, and provided her with a fake ID.

She also gave her amphetamines, Michelle says, “so I could make it through a day of eighth grade after staying up all night with her. Tamar introduced me to real music—Bessie Smith and Paul Robeson and Josh White and Leon Bibb. And I, who’d been listening to the [mainstream] Kingston Trio, was just entranced.” When we spoke in 2006 Tamar told me, touchingly, “In Michelle, I saw someone I might have been. I wanted to give her the good girlhood that was taken from me. I wanted to champion her because no one had championed me.”

The Start of the Mamas & the Papas

After Tamar divorced Stan Wilson, she took Michelle, by then a young teenager, to San Francisco—with Deborah Elizabeth in tow—and the two painted their small apartment lavender.

While hosting salons attended by black and white avant garde eminences like Lenny Bruce and Maya Angelou, Dick Gregory and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, she introduced Michelle to the tall, authoritative folk singer, John Phillips, who would become Michelle’s husband. Their Mamas & the Papas turned the key from folk music to just-pre-hippie counterculture music.

Tamar did all that.

“But,” Michelle says sadly, “I think what had happened to her as a child made her lose her mind.” And while Tamar “championed” Michelle, there was someone she did not champion: her own daughter, the one she raised from birth rather than had adopted out, her daughter with Stan Wilson—Deborah Elizabeth, who now uses the name FaunaElizabeth.

FaunaElizabeth Hodel Wilson Simon is a quiet, vulnerable woman who is a photo editor and currently works in retail. At 63, with an adult daughter who suffers from multiple sclerosis, she tells a wrenching story of how her mother Tamar had been so warped by her own upbringing, she basically “used me as a chip” to keep her sick, powerful father’s love.

Not a Reese Witherspoon Movie

FaunaElizabeth Simon, Tamar Hodel’s second daughter, who is a survivor of shocking child abuse. Image: Courtesy of FaunaElizabeth Simon.

I had wanted this story to have a #MeToo happy ending, or at least a happy middle: a hideously abused incest victim daughter of a likely killer—a 14 year old wrongly sent to juvenile hall for telling the truth!—becomes the parent she herself didn’t have. But, sadly, the truth was different. We feminists don’t like it when abused women do not triumph. (Confession: In the 1990s I quit the board of directors of a major domestic violence organization because the sheltered women did not live up to my fantasy of wonderful, grateful reformed women.)

Life is meaner, and psyches more damageable than we wish them to be. Wounds leave scars, and scars lead people—even “should-be-heroic” women—to do bad things. Destroyed girlhoods can have ugly consequences.

Her mother would send her overnight to men’s homes when she was 11.

FaunaElizabeth told me this the other day, her voice shaking: “My mother used me as a vehicle to make money. She hated being poor, so she would send me overnight to men’s homes when I was 11. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do there! They wouldn’t rape me in a violent way, but I would comply. I did whatever my mother wanted me to do.”

When she was 13 her grandfather George Hodel drugged her and for seven hours she would intermittently wake up, naked and spread eagled. That is how heinously and tragically Tamar Hodel wanted to stay in her incesting father’s good graces and get money from him: she gave her daughter to her grandfather to molest.

FaunaElizabeth and I have spoken several times. She is a gentle woman, and it feels to me that she is sincerely telling the truth.

Because of the sexual abuse, FaunaElizabeth got herself on birth control pills. She wanted a free life and an education. But, she says, her mother Tamar switched them out for fake pills, and she became pregnant. Michelle Phillips tried very hard to help FaunaElizabeth—“she offered to get me an abortion,” FaunaElizabeth says—but Tamar nixed that. FaunaElizabeth had a baby at 15, just like Tamar had. Tamar used her daughter’s baby to acquire welfare payments for herself. In addition, Tamar was verbally and physically abusive to her daughter—often calling her the N-word.

When I asked FaunaElizabeth why she changed from her given name, Deborah, to her older half-sister’s name, she said that in her teens “my mother hated me so much and mourned the loss of her daughter Fauna, that I wanted to `kill’ Debbie and become Fauna.” Not `replace’ her but become like the Fauna her mother loved.

What a girlhood to overcome!

An Astonishing Act of Kindness

Amazingly, FaunaElizabeth finally broke free, got married, had another child, and forced herself into a normal, reasonably happy life with a great deal of therapy. And she forgave her mother, who went on to become a hippie and have three sons: Peace, Love, and Joy.

And she forgave her mother. This fills me with awe.

FaunaElizabeth says: “I triumphed! I am still triumphing. I want people to realize I’m not a victim; I’m a survivor. There are a lot of people like us out there. And I want to be a voice for those people.”

She pauses, then says, with admirable nuance: “My mother was not a monster. Unless you were born with a mental defect, monsters are not born, they are made. They are made by their environments.” George Hodel and the world that let him get away with what he did was such an environment.

Let’s hope that telling this whole truth—the part in the “inspired by” series and the wider truth you’ve just heard, even if it is unattractive—will help us all as we deal with the past and the present in the giant area of concern—abuse of women—that we have wisely and ambitiously and nobly taken on.

A version of this story was originally published in February 2019.

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

0 Comments