Is there a woman who was alive in the 1970s who didn’t want to be like Mary Tyler Moore, a.k.a. Mary Richards, the associate producer of Minneapolis’s WJM-TV’s six o’clock news.

Mary Richards held the whole office together, even though she called her boss, the charmingly gruff Ed Asner, “Mr. Grant” instead of “Lou.” (We knew the “Mr. Grant” bit was campy.) She had fabulous up-flipped hair, exactly the knockout figure we all wanted (which could only come from years of dancing), sleek skirts, and matching sweaters. (Could “straight” office clothes be so cool? My God, suddenly they were the greatest!) She had a glowing air of decency and integrity. She also had an expressive range that zigzagged from incredulousness to befuddlement to shrewd irony and back.

I hosted dinners every Saturday night in my funky West Village apartment so my friends and I could watch The Mary Tyler Moore Show together.

Yes, there was something in her voice that (if you closed your eyes) was tense and shrill, but we ignored it or thought it accidental and charming—not what it really was: a clue.

In 1970, I hosted massive-salad dinners every Saturday night in my funky little West Village apartment for three close girlfriends so we could watch The Mary Tyler Moore Show together. The tie-dyed curtains were still on my windows, but that game—tries-too-hard hipness—was getting tiresome.

I’d been proud of that hipness. Some of it was certainly good—waitressing at three serious-jazz clubs, as if this corny Beverly Hills High cheerleader could turn herself into another creature entirely. The friends who walked up my rickety stairs every Saturday night and forked into my hearts of palm and chick peas and eggplant and grilled chicken concoctions as Mary threw her hat triumphantly into the Minneapolis air (“You’re gonna make it after a-all!”) had their own resumes of hipness. One worked and modeled for the ultimate boutique, Paraphernalia; another had become the muse to one of Tangier’s most darkly glamorous expatriate literary men. We watched Mary’s show on my tiny TV, and as we did, we saw materialize the woman who would lead us to our next place.

Oh, was Mary Richards cool! Urbane. Very suddenly-‘70s. Living alone but never lonely. We friends were all a combination of Rhoda and Mary to one another. She was obviously smarter and more self-aware and more optimistic than the guys in the office (especially ridiculously bloviating “star” newsman Ted Baxter, of course, but also perennially woebegone news writer Murray Slaughter). We knew she would advance the way she was destined to, and in that moment —one year from the launch of MS. Magazine (which I began, gratifyingly, to write for), we watched ourselves hitching a ride with her. You didn’t have to get an office job; you just had to elevate certain values—dignity, classiness, self-acceptance, cool, ironic awareness, calm determination.

And it is because we hold Mary Tyler Moore, all these decades later, in the Winner spotlight—as someone who became our role model and next-steps agent—that watching the entertaining and revelatory new documentary Being Mary Tyler Moore has an undertow: It’s such an unexpectedly poignant and even sadly shocking experience.

Read More: Cass Elliot’s Daughter Talks About the Star’s Bravery

Five Reasons to Love the Mary Tyler Moore Documentary

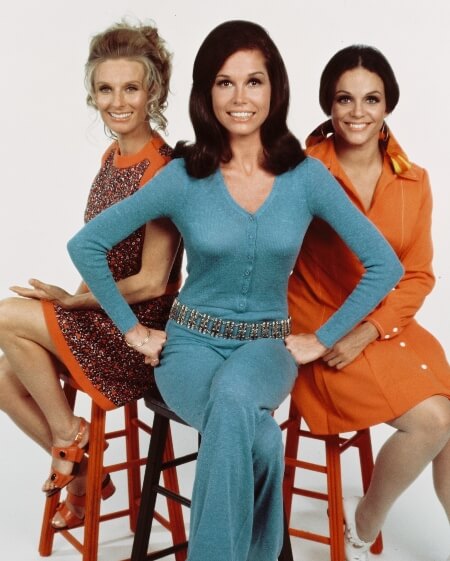

With her TV gal pals, wearing PANTS!

But before we get into why that is: First, five very cool things about the documentary of the life and work of the performer who was born in 1936 and died on January 25, 2017.

1. It reminds us how stunningly good The Mary Tyler Moore Show was. The writing; the acting! A scene where Mary tries to substitute “Lou” for “Mr. Grant” has the two of them performing a kind of hilarious, intimate call-and-response. (One could even say these two were a whole new definition of subliminal lovers.) And the appeal of this all-White-casted show was surprisingly inclusive. It is Lena Waithe—Black and queer—who credits watching the show as her most important lesson in comedy. Her love for it is the reason the documentary was made, and she is one of its producers.

2. It’s a lived swipe against the patriarchy. We see (in the opening scene) smug, sexist David Susskind interviewing Mary Tyler Moore while not letting her get a word in edgewise until, in her own way, she zaps him. (The documentary’s highly esteemed director, James Adolphus, related to that moment because, he said, in a post-screening conversation, as a “half-Black, half-Puerto-Rican man,” he related to having to go up against such “patriarchal” attitude.)

Until now, we never knew the belligerence with which network executives tried to hold on to the no-pants rule for women.

3. Like any good documentary, it surprises us. The pilot of The MTM Show bombed? Who knew? But it did and could easily not have lived to see another day. Executive producer Jim Brooks was terrified. Elevating Valerie Harper’s Rhoda was a good part of the saving sauce.

4. The documentary gives us pieces of the sexism of earliest ‘60s TV. Before she played Mary Richards on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Mary played Laura Petrie, the fictional former-dancer wife of the fictional comedy writer Rob Petrie, on The Dick Van Dyke Show. Mary’s character Laura was the first TV wife grudgingly allowed to wear pants, not a dress. What a huge deal that was! How angry the morals people were that the pants too closely hugged Mary’s derriere. We have long been aware that Lucy and Desi were not allowed to sleep in the same bed in I Love Lucy—but we never knew the belligerence with which network executives tried to hold on to the no-pants rule for women.

5. Did we ever see—or, if we did see it, did we remember—how Gloria Steinem upbraided Jim Brooks for having Mary Richards call Lou Grant “Mr. Grant”? Why doesn’t she call him Lou? Steinem asked, with appropriate anger, in front of a live audience. “It doesn’t feel right,” Brooks answered Steinem. He was instantly, loudly booed. (“Nice, seemingly feminist-friendly Jim Brooks—you, too?” I found myself thinking, like Michael Corleone to Fredo.) The exchange led to that hilarious scene when Mary—self-spoofingly—tries to call Grant “Lou” and simply cannot do it.

But feminism is alive and well when, at the very beginning of the series, Mary is questioned by the cynical (sadly, female) human resources woman at the station who sneers at this unmarried woman’s last name: “It’s still Richards?”

“Yes,” Mary bests her. “And it’s still Mary.”

Throughout the documentary, Mary’s film work is touted in voiceovers by Julia Louis Dreyfuss, Rosie O’Donnell, and Katie Couric and, in real time, by—among many other—no less a comedy eminence than Lucille Ball. And her searing, Academy Award-nominated performance in the Robert Redford-directed Ordinary People is recalled. In that film, she plays a brittle and unhappy woman who, after the death of one of her sons, finds herself unable to love the living one. “Robert, you sneak!” she is shown saying through an interviewer, affectionately annoyed at Redford for immediately intuiting the hidden piece of this fabulously disciplined woman: She was sad, and loving did not come easily in the family she grew up in.

The MTM Brand

On the set of Ordinary People, for which she was nominated for an Oscar

Mary grew up in working-class Brooklyn. Her parents were both (lifelong, it would turn out) serious alcoholics. She was so respectful of her father, clerk George Tyler Moore, that she used his middle name—Tyler—between her own two. (In truth, it also added an aristocratic ring to her name.) She used her childhood-honed talent as a dancer to help shield and support her parents. She was devoted to and protective of them, always.

She married actor Richard Meeker right after high school. The aftermath of a miscarriage showed her to have alarmingly severe diabetes. But that didn’t stop her: She danced and mastered acting. She had a son, Richard Junior—Richie—Meeker. Her younger sister, when a love affair went wrong, committed suicide. Diabetes, alcoholic parents, a tragically and fatally troubled sister. Nevertheless, she persisted.

Her enormous talent transformed the sorrow and its protective, brittle shield into her Oscar-nominated role.

After her early marriage to Meeker, Mary made a very good marriage to polished, highly successful entertainment executive Grant Tinker, and her career took seriously off; The Mary Tyler Moore Show was launched and produced by Tinker. Tinker had two sons of his own and—in one of the documentary’s saddest revelations—Mary’s relationship with her own son, Richie, fell into the shadows.

When her marriage to Tinker ended—she wanted and needed to be single for the first time in her life—Mary moved to New York. It was exciting and productive, but at night she had begun to drink. This was the “sad” Mary that Robert Redford saw—and her enormous talent transformed the sorrow and its protective, brittle shield into her Oscar-nominated role.

The role freed her. She became boldly, admirably honest about her drinking—and she raised massive amounts of money (and consciousness) to help other women with addiction problems. She raised even more money for diabetes research and treatment.

Tragically, her son Richie, who had always had a collection of loaded guns, shot and killed himself (by accident or . . . not, the documentary is careful to say) on October 14, 1980. He was 24.

Finding Happiness at Last

Mary met her third husband—Dr. Robert Levine, 15 years younger–one night when her mother fell ill on a major Christian holiday and Levine was the only doctor working that day in the Catholic hospital. The worldly, complex actress and the solid, protective, but experientially-almost-innocent young doctor fell in love. That he made her a tuna sandwich in the middle of the night meant more to her than the jewels that Tinker and other men had given her. (You can’t make this stuff up, right?)

Drinking, and diabetes, and sadness, and—perhaps—guilt had beaten her down. Now it was time for someone to help her.

Is this portrayal of Levine as her too-good-to-be-true savior offensively sexist? No, because she deeply believed that this is what he was to her. From a very early age, she had always done for others. But drinking, and diabetes, and sadness, and—perhaps—guilt had beaten her down. Now it was time for someone to help her.

At a “roast” of a wedding shower—Betty White is hilarious—Mary’s mother read a poem: “Roses are red, violets are blue-ish; You once were a Mick, but now you’re Jewish.”

But at the wedding, officiated by priest and rabbi, Mary’s father was “so Christian,” a friend diplomatically put it, that he hesitated to stand under the chuppah. But there was more to George Tyler Moore’s unattractive character: When his only son, Mary’s brother John, lay dying, this man—his father—said: “I’m supposed to love you, but I don’t.” Yep. Having and loving and protecting a father like that: That must have been very, very hard for Mary.

The documentary ends with a scene—Mary is palpably very happy—of her and Levine filming one another with their horses at their Millbrook farm. And it uber-ends with a much, much earlier clip of her and Ed Asner dancing, half-Saturday Night Fever-style, half-jig-style together. Wait! (I nearly jumped out of my seat.) Lou Grant can fucking dance?! That’s how good Asner was: He’d become Lou Grant to me! And that’s how good she was.

And that’s why she will always be the Mary—“Mare? Mare?” as Rhoda would say, needing advice from her bestie—who we girls of a certain age learned to live our own best lives through.

But only now, with this documentary, do we know what Mary Tyler Moore had to persist through and graciously, determinedly hide in order to give her best self to us.

Read More: Molly Ivins Documentary: A Maverick’s Moment on Screen and in Spirit

0 Comments