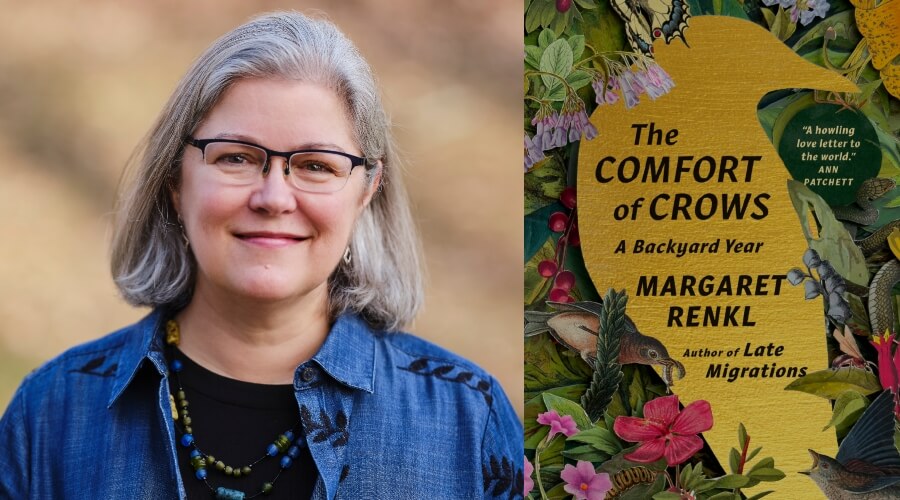

Fifteen minutes a day. That’s all it took to change the course of Margaret Renkl’s life and career. One month of 15-minute writing sessions produced her first essay for The New York Times, back in 2014. More followed. Then in 2017, the Times hired her to write a weekly column for the opinion page, described as “flora, fauna, politics, and culture in the American South.” Now Renkl’s third book of essays, The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard Year, is a national bestseller, dubbed “an instant classic” in one review. Novelist Ann Patchett praised the book as “a howling love letter to the world.”

Join us for a special virtual interview with Margaret Renkl on Monday, Dec. 11th at 6:30 pm ET. RSVP here.

Renkl first carved out those 15-minute writing sessions when two of her three sons still lived in their Nashville home. Months before, her mother had died suddenly. Then her in-laws moved nearby, both with serious ailments needing her attention. Swamped with grief, caretaking duties, and a full-time editing job, Renkl says “it felt like I was just this raw nerve in the wind.”

So Renkl began waking before dawn to sit with only her pen and notebook–no email, no computer. She told herself she would stick with it every day for a month. Some days, she could only eke out a few words. By the end of the month, she had that one essay–then, after the Times accepted it, she waited nearly nine anxious months for it to finally run in the paper. But she kept writing.

Read More: Author Ann Hood on Staying Happy Even through Tragedy

Success Comes in Small Steps

“Fifteen minutes a day is not too much to ask, to give yourself permission to have that little bit of time. It made me feel so much better to be able to do something just for me–but also to sort through all these huge life and death things happening in my life. And it reminded me that writing is how I’ve always tried to understand and make sense of the world. So I stuck with it.”

Eventually, at age 57, Renkl had written enough to fill her first book, Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss (2019). Next came her essay collection Graceland At Last: Notes on Hope and Heartache from the American South (2021). She wrote her third book, The Comfort of Crows, during the worst of the pandemic. “The television may be full of terror…but the trees are full of music,” she writes in that essay, about her first steps outdoors after falling ill with COVID.

Fifteen minutes a day is not too much to ask, to give yourself permission to have that little bit of time.

Renkl divided this book into four seasons and 52 essays, marking each week’s observations in her backyard and neighborhood of 28 years. She begins with her “first bird” sighting of a crow on January 1, a clever bird representing the hope of renewal. December ends with two bluebirds studying their old nesting site, interspersed with a debate she and her husband have about moving to another, quieter place, now that their sons are grown. Sprinkled throughout the book are her “praise songs,” a few lovely lines of insight.

One strength of the book is how Renkl melds her years of journalistic training with the power of poetry, her first love, to create poignant narratives. She often bears witness to the ways massive global changes are transforming our world, from a fox ill with mange to the loss of native trees. “It’s not what’s happening to the polar bears,” she says. “It’s what’s happening to the blue jays. The same things are happening to our close-by nature. It’s indisputable.”

The Power of Stories

Humans are storytelling creatures, she says, and we tend to respond better to stories than to charts and data. “It’s harder to deny what’s happening when we see it with our own eyes versus when we read, say, the numbers involved with biodiversity loss,” she says. “It stops seeming like a math problem. It becomes something that’s personal.”

Yet these are no screeds: in her books and in her columns, Renkl trains her eye mostly on the beauty and joy of interacting with nearby nature. “I don’t want to imply that it’s all terrible and sad,” she says. “I believe we are motivated to save what we love. It’s easier to feel distant from what is happening at a literal distance from us, but also what is happening at an emotional distance from us. If we don’t notice the baby birds or the butterflies or the turtles, how will we ever change in time to save them?”

It’s harder to deny what’s happening when we see it with our own eyes versus when we read, say, the numbers involved with biodiversity loss.

She sees another dire threat to “nearby nature” in the nationwide trend of builders tearing down smaller homes to build much larger houses. She is especially disturbed by builders who scrape the entire lot of trees and plants then spray the dirt with pre-emergent poisons, before planting sod grass from lot line to lot line.

“It feels very tragic to me. We’re losing that habitat where wildlife has accommodated our existence. They have nowhere to go. There are no more trees to build nests in, there are no more weedy flowers for the bees.”

She tallies the losses: the box turtles, tree frogs, garter snakes, and lightning bugs–all of which, she notes, are the sort of nature that most interest children. “I find it so mystifying. It’s just fashion. There’s no good reason to prefer turf grass to wildflowers. I don’t think people give any thought to it at all. Most traditional gardens aren’t yet in bloom when the bees and butterflies wake up in spring.”

Southern Roots

Renkl lived much of her early life playing in the natural world. She was born in Andalusia, Alabama, where she lived until she was seven, then moved around the state before her family settled near Birmingham. She earned degrees at Auburn University and the University of South Carolina before moving with her husband to Nashville, where they taught school and reared three boys.

Her rural red-state background may seem unusual for the big-city opinion pages where she appears each Monday. “What surprises people is that I still love the South so much, that I love my homeland in spite of anything I don’t love about it,” she says. Her soft Southern accent is still intact; she’s puzzled by people who move away from hometowns and lose their drawls.

She’s puzzled by people who move away from hometowns and lose their drawls.

Renkl conceived The Comfort of Crows as a devotional on the beauties of the world, much like the old illuminated church manuscripts. Her younger brother, artist Billy Renkl, created full-color collages to pair with each of her 52 essays. “We were that feral generation where parents told their children to go outside and play,” she says. “As long as we stayed together, we could go wherever our little feet could carry us. So he has the same feelings about wildflowers and birds and clouds and stars that I have.”

Her brother’s images convey the book’s message more than text would alone, she says. “It was really fun to watch his interpretation of those weeks of the year unfold next to mine. I’m hoping the book will inspire people to contemplate and celebrate these little beauties of the natural world. It slows you down and settles your soul to see those beautiful collages.”

Reconnecting with the Natural World

One of her hopes for The Comfort of Crows is that it will inspire her readers to pay more attention to the world outside, and maybe plant a pollinator garden. “Once you do that, you see how much joy it gives you,” she says. “It’s a gateway drug to conservation.”

Renkl often examines how divorced we are, as a nation, as a society, from the natural world.

Renkl often examines how divorced we are, as a nation, as a society, from the natural world. “We don’t even know how much this hurts us. We are still creatures at heart, yet somehow we’re living at this incredibly fast pace, and our eyes are always glued to a screen and everything’s moving at lightning speed. Then we take a cup of coffee and sit outside and listen to the birds sing, and we feel so much better. It helps us remember who we really are.”

Some of her fondest childhood memories are from the weeks she spent roaming around her grandmother’s farm in Lower Alabama. “Most people in this country aren’t very far removed from the farm. We evolved to be in close communion with the land, but our lives don’t support that anymore. When people do step outside, they don’t even realize that they’ve missed it until they have it again.”

One benefit of age, of her children being older, she says, is having more time to seek out these experiences. “For me, I have a little more time to remember who I am. And who I am is a girl who grew up in the woods, barefoot, next to the creek.”

Read More: Love, Loss, and What I Gained: Delia Ephron’s New Memoir Feels, Yes, Like a Rom-Com

0 Comments