Editor’s Note: With the news that Christiane Amanpour has been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, we’re republishing this vivid profile by Sheila Weller. We have long admired Amanpour, and do so even more now that she’s using her ordeal to help other women avoid the same fate. “I’m telling you this in the interest of transparency,” she said in her on-air announcement, “but, in truth, really mostly as a shout-out to early diagnosis. To urge women to educate themselves on this disease, to get all the regular screenings and scans that you can, to always listen to your bodies, and of course, to ensure that your legitimate medical concerns are not dismissed or diminished.”

***

On a desultory day—Monday—when the campaign of a Senatorial candidate accused of sexual harassment of teenage girls was once again funded by the Republican party, and a President whacked the largest amount of federally protected Native American heritage and environmentally significant land in U.S. history, and when a tax bill that will punish the middle class seems certain to become law, some happy news popped out of the blue. The most accomplished, and brave international justice journalist of her generation—a woman who has asked the toughest questions of presidents, dictators, and warlords (and made them quake)—will take over an important time slot from a male host, whom we once thought charming, if socially unctuous, before he was accused by nine women of sexual harassment.

In this moment, when brave women who have spoken out have inspired others and earned Time Magazine’s Persons of the Year title, it’s emotionally satisfying.

Christiane Amanpour’s program “Amanpour” will replace Charlie Rose’s show—thus far on an interim basis for the first half hour—and there are so many reasons to celebrate. First, there’s justice after irony—and unfairness. For a decade and a half, for CNN and CBS’s 60 Minutes, Amanpour brought us dozens of powerful injustice stories, mainly concerning women and children, from all over the globe, especially in much-ignored corners of Africa and India, as well as the the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Asia. Rarely has there been a more internationally prolific journalist. In one six-year span alone—2000 to 2006—Amanpour covered stories in (take a breath) Sudan, Chad, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, Kenya, Darfur, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Iran, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Kosovo, Italy, France, Spain, Russia, and the Ukraine, as well as New York and Washington D.C.

Before that, during the early nineties, her courageous nightly stand-up war reporting, with explosions in the background, drove home to America the fact that there was a genocide being perpetrated in Bosnia. Yet when, in 2008, she came home to the States to for the well-earned easier gig—an authoritative in-studio interview show—she didn’t quite make the grade in that presumably less challenging genre. First, her 2009 CNN show was made second fiddle to Fareed Zakaria’s and suffered in ratings; then her much-hailed host slot of ABC’s This Week, which started the following year—and, quite ridiculously, marked the first time a female had hosted a Sunday show ever—didn’t even last 16 months; George Stephanopoulos re-replaced her. It was thought that her tone was considered “off” for a Sunday show—it’s possible that being a woman who was crisp rather than “warm” had something to do with it.

We Need Her Now

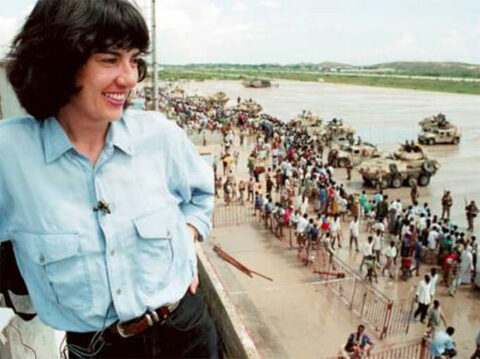

Chistiane Amanpour being interviewed about Fake News.

Secondly, we’ve missed her! And we need her! Until recently, she has been living in London and has been seen less on American television than she was before. The woman who, as a relative unknown in May of 1994, had the nerve to bawl out President Clinton, on live TV for not taking Bosnia seriously is precisely who we need to talk truth to power: the “fake news”-accusing current administration. In fact, two months ago she discussed precisely this on a TED Talk.

Journalists on all platforms have done hard, strong work for the last intense year. But, among this tough and admirable crew, Amanpour is particularly uncompromising and fearless. We need that more than ever right now—and it doesn’t hurt to add this Amanpour-brand rigor to Rose’s 11 p.m. slot, which used to be a mix of culture and entertainment in addition to politics.

It’s not just gender justice that a woman with a flawless personal reputation is replacing a man accused of repellent actions.

And finally, there is, if you will, a bit of dramatic, sentimental gendered meaning. It’s not just gender justice that a woman with a flawless personal reputation is replacing a man accused of repellent actions. In this moment, when brave women who have spoken out have inspired others and earned Time Magazine’s Persons of the Year title, it’s emotionally satisfying. Twenty-five years ago Christiane was deeply inspired by a little-known, bold, and colorful female mentor. Christiane’s life was changed by that collegiality. Taking this new job, at a critical time, is a kind of later-life continuation of that loyalty-and-bravery-based bond between the two women who showed a fearlessness about life-threatening reporting and shared a risk-filled commitment to telling the world the truth.

Why Christiane Inspires

Christiane Amanpour doing the reports from Bosnia that made her famous.

I got to know a lot about Christiane when I was researching her life and career for my 2014 book The News Sorority, which also featured the lives and careers of Diane Sawyer and Katie Couric. I did not interview her, but I talked to dozens of her friends and colleagues, including two of her three sisters. I know what a strong and inspiring older sibling she was to the younger girls. I know how she became effortlessly cosmopolitan by having a wealthy, non-religious Muslim Iranian father and a lovely, religious Catholic English mother—and how, married to a Jewish American, Jamie Rubin (former diplomat, currently an appointee of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo), she ended up feeling that all three of the world’s great religions throbbed in the bloodstream of their son Darius.

I know how, when she started boarding school in England as a preteen, she cheekily let the other girls in that more provincial school infer that she was a Middle Eastern princess. I know how she found her life’s work almost accidentally, when her sister Fiona ran off with a rock singer after paying tuition for a journalism course in London and Christiane did not want the tuition to go to waste. I know how the world-shaking 1978 Iranian Revolution forced the Amanpours to uproot themselves on a moment’s notice and how her commitment to telling the worlds’ stories came from that dramatic forced exodus, as well as her unhappy confrontation with young Americans’ imperfect understanding of the complexities and histories of her native country (“Bomb, bomb, bomb Iran!” college kids would sing), which had suddenly transformed into a theocracy.

I know that she was John Kennedy, Jr.’s close friend and roommate when he was at Brown and she was at the University of Rhode Island, and that she remained his lifetime confidante and later gave her son the middle name “John” in his memory. I learned how she cried when, with an accidental whack of car keys to her mouth one college day, John teased her that her chipped tooth would mean she would never be a newscaster.

Christiane in Somalia

I know how she insisted, at the then-fledgling network CNN (nicknamed Chicken Noodle News by some) in the ‘80s that she would be an on-air newscaster even though she was everything a female anchor was not supposed to be, especially in the South at the time. (CNN was based in then-sleepy Atlanta). She had messy brunette hair instead of a coiffed blonde ‘do. She was not a smiler. She was someone who indifferently wore dark jackets, not bright pastels. She eschewed makeup. She was not an American-girl-next-door, and she had an unpronounceable name and a clipped British accent. She’ll get on the air over my dead body, several producers as much as said. She proved them wrong, every one of them.

I know how, having finally gained a foothold as a weekend anchor in New York, she left on a dime to fly to London when her youngest sister Leila lost her leg in a bicycle accident. Her compassion and tough love got Leila through the ordeal with courage and without self-pity. I know how she was such a good friend—and competent multi-tasker—that she insisted on flying from Egypt back to New York to host a book party for a good girlfriend Bella Pollen, even when she was in the midst of scoring an exclusive interview during the tumultuous Arab Spring with just-ousted Hosni Mubarak.

The Important Bond She Formed in Bosnia

Margaret Moth, Chrisitane Amanpour’s mentor and camerawoman in Bosnia.

In 1992, Christiane was one of a number of reporters and camera people in one of the most dangerous war zones in recent times: Bosnia. This was a war in the middle of a city—Sarajevo. Mortar shells pierced hotel rooms; journalists made their way, without body armor, down a street that was, for good reason, called Sniper Alley.

An icon in the group was a New Zealand war photographer named Margaret Moth. Slightly older than many of the others, at 42, Moth was incredibly colorful: She chomped cigars; she drank everyone under the table; she told true tales of having jumped out of planes barefoot and shot footage of rebel warriors when their guns were pointed at her head. She was stunning and bold, and the women on the team, like Christiane, took her as their hero.

One day in July 1992, Margaret Moth was driving down Sniper Alley in an unarmored car, as was customary then, when a bullet whizzed right at her. It shot through her cheekbone and exited the other side of her jaw. The bottom of her face was blown off.

“I said yes because I couldn’t say no. Margaret was our champion, and we wanted to be her champion.”

She was immediately air-lifted to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and the entire Sarajevo team was temporarily disbanded. Christiane quickly flew to Minnesota to see her mentor. After the emotional visit, Christiane was told in no uncertain terms that, though the Sarajevo team was being carefully reconfigured, she did not have to return. Friends urged her not to go back: It was safer to be anywhere else than Sarajevo.

A friend and producer, Parisa Khosravi, remembers being with Christiane, talking her out of returning, when, “in a very dramatic moment,” Parisa told me, “Christiane gritted her teeth and said, ‘I’m going back.’ Seeing Margaret with her jaw shot out steeled her to go back to Bosnia.” Christiane has explained it this way: “I said yes because I couldn’t say no. Margaret was our champion, and we wanted to be her champion.” It was in Bosnia that Christiane’s sterling career was made. “I know to this day that if I hadn’t said yes, then I probably would never have gone back and I never would have done this career.”

That career spurred justice and knowledge and outrage for many. And now great inspiration for taking care of ourselves.

A version of this story was originally published in November 2017.

0 Comments