She grew up living what she thought was a carefree childhood in the Deep South. She occasionally sensed that her father and uncle were up to some “good trouble,” but school and life went on. Like many others of that time, Little Karen Gray was unaware of something called the KKK, and hardly even noticed that the unpaved street where she spent her time was named after a man who epitomized the worst for her people. And, she says, “as certain as the sun shines, the Gray family was in church every Sunday morning.”

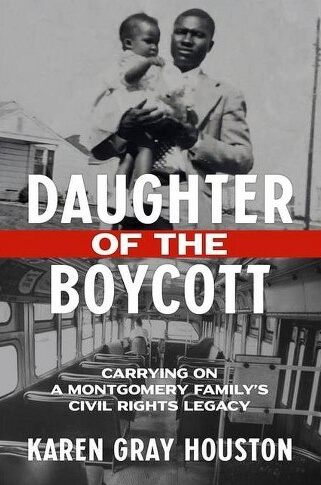

She is Karen Gray Houston and she has written a memoir about her family in the pivotal years of the civil rights movement called Daughter of The Boycott: Carrying On A Montgomery Family’s Civil Rights Legacy. The book is theoretically about when and how Blacks stopped using segregated buses in Alabama’s capital city in 1955. But the story becomes about much more.

That story has been making some news lately, due to the amazing but under-appreciated work of her father, Thomas Gray, and her uncle, Fred Gray, now 90. Fred Gray was a major figure in the Civil Rights movement, a young lawyer who represented Rosa Parks among others. Martin Luther King called him “the chief counsel of the protest movement.”

“I began researching five years ago,” says Houston, from her current home in Clover, South Carolina. “During that time, I moved into my grandmother’s old house in Montgomery, and I soon realized that, more than anything, this was about a community of 40,000 who took part in the boycott.”

Read More: Stacey Abrams, Powerhouse and Power Broker, Delivers Big in Georgia This Week

The Montgomery Bus Boycott Remembered

Amazingly, many people were—and are—still around for her to interview. She joined Montgomery civic organizations, like The Friendly Supper Club, where she would announce her project and find herself surrounded by folks responding with words all reporters covet: “You’re going to want to talk to me.” That one came from another daughter—of the racist sheriff who had done everything to stop the bus protests. There was a 90-year old woman who said she had had a Black maid during the 50s, and mentioned the maid was still alive too. “Suffice to say their stories were very different,” says Houston.

She also tracked down Claudette Colvin who, at 15, and nine months before Rosa Parks, refused to give up her seat on the bus and became part of a famous lawsuit. And then there was the 100 year-old former White minister, now in a retirement community, who recalled being run out of his church because he spoke of the evils of segregation. Houston also dove into the city’s archives and discovered letters from angry anti-boycott locals suggesting authorities “send these people back to Africa!”

But mostly, Houston came to truly appreciate the contributions of her own family. She had done an oral history with her father, Thomas Gray, before he died. He had run an electrical repair shop, was a sometime radio announcer, and helped coordinate the boycott. He set up stations for boycotting bus riders to get rides to work. He went on to become a lawyer and judge. There was also “Uncle Teddy” (Fred Gray), who, at 29, argued before the Supreme Court, winning a landmark ruling that declared gerrymandering an unconstitutional means of disenfranchising African-Americans.

The Real Rosa Parks

Fred Gray’s most notable client was Rosa Parks, with whom he had a close and collaborative relationship. Reading this book, one will never again think of her as a quiet, submissive seamstress. In fact, Parks was an active member of the NAACP, and she and Gray carefully planned the moment that would spark the year-long bus boycott and make her a heroine who mattered. “I only met her once,” says Houston, “and there was this serene calmness about her.”

Parks is memorialized throughout Montgomery. When I visited a few years back, I went to the museum in her name, where, yes, you can board the bus and yes, ask yourself: What would I have done? Parks has clearly had her moments, including walking the red carpet at the Oscars one year where she was asked “who are you wearing”? Her blank expression was priceless. But what about the man who represented her, and so many others, in their causes?

Which brings us to the street controversy. “The mayor has told Fred he’d like to create some kind of permanent memorial for him,” explains Houston, “and my uncle said, ‘well, you could re-name the street where I lived.'” The name? Jeff Davis Avenue, as in the President of the Confederacy. “Why the heck they gave that name to a street in a poor black district is beyond me,” says Houston,”but we didn’t really think about it growing up.”

The Road of Pain

The issue has become a red-tape nightmare, with a reluctant Republican governor and commissions debating a law about when, or if, monuments—including streets—that are more than 40-years old, can come down or be altered. But the proud niece promises, “this is not going away overnight.”

Her family’s story is, of course, catching a moment of reckoning. “Yes, it’s turned out to be even more relevant than I expected,” says Houston, whose first chapter discusses police violence against Blacks—in 1970. “It’s unfortunate that once again it takes White brutality to make [the conversation] happen.”

She will continue to fight for her uncle’s wish. She retired a few years back, following a long career as a broadcast reporter. Among the many stories she covered on TV and radio was another issue involving a hauntingly familiar mode of transportation—the 1970s school busing battles.

She feels blessed to have had the time to look back. The book went through many drafts, mostly focusing on the issues rather than her personal connections. It was Fred Gray who finally told her, “it’s your story. Claim it.”

“In the end,” she says, “it gave me a chance to get acquainted with the place where I was born and with those who raised me. It was a way for me to finally say thank you.”

Read More: 8 Women, 6 Days, 116 Miles: A Walk to Channel the Spirit of Harriet Tubman

0 Comments