Marie Colvin could have been a character of a Hemingway novel. Blonde and glamorous, she wore a black patch over her left eye after it was blinded by a grenade in Sri Lanka’s civil war. The American-born Colvin had a formidable reputation as a war correspondent for the British newspaper The Sunday Times, dodging death in some of the world’s worst conflicts—Iraq, Chechnya and Kosovo, among others.

But in February 2012, Colvin’s luck ran out. She was killed, along with French photographer Remi Ochlik, after Syrian government forces shelled the makeshift media center from which they were working in the western city of Homs. She was 56 years old.

The question about journalists who cover war is: Why do they keep going into these areas?

Colvin’s remarkable career is now being remembered in books, a movie, and a documentary. They detail a life filled with adventure and parties, but there’s also the PTSD, the nightmares, and the hard drinking.

The question woven into each of these accounts of Colvin’s life is why did she keep going into these areas, knowing her chances of being killed were high? Some people thought she was addicted to the adrenaline surge of war, others believed she felt compelled to tell the stories about ordinary people caught up in the brutality of armed conflict.

Many journalists who report from high-risk areas eventually find themselves at a crossroads, having to decide if they want to keep putting themselves into harm’s way to cover a story or say enough is enough. It may be the desire for a more normal life, perhaps they have seen too much destruction and suffering, or they understand the time will come when they’re going to take one too many risks, as Colvin did.

I found myself in that position a few years ago.

My 30 Years as a War Correspondent

I spent more than 30 years on the road as an international correspondent for various radio networks—including NPR for the past 18 years—which took me to flashpoints from Saudi Arabia and Iraq to Afghanistan and Lebanon. It was a career path I chose when I was in my mid-20s and saw Ann Medina, a correspondent with Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, reporting from war-torn Beirut. She stood amidst the rubble of bombed-out buildings, wearing a billowing white shirt tucked into her jeans. I decided right then that was who I wanted to be and what I wanted to do—it seemed such an exciting and exotic life.

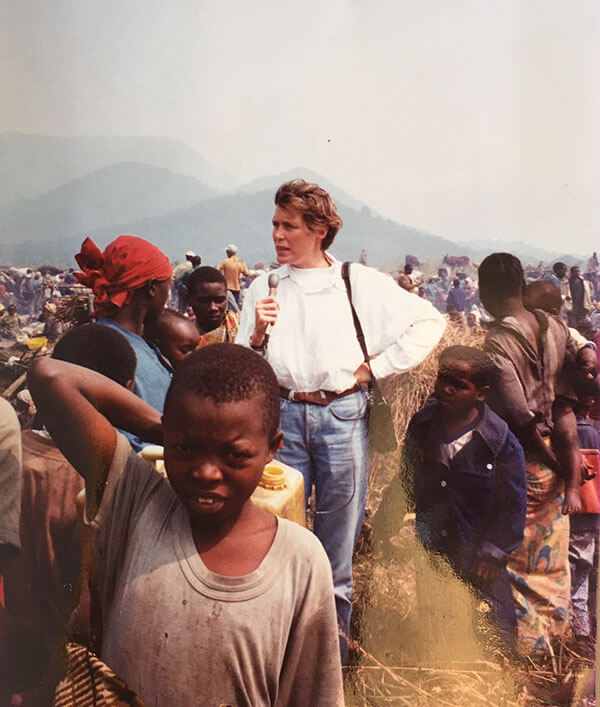

In the opening days of the Rwanda genocide, a Hutu militiaman held a machete to my neck, threatening to kill me.

My career choice was perfect for me. It’s allowed me to see the world and interview fascinating people making history. But life on the road in far-off places can be tough, especially when phones don’t work, there’s no electricity, and you’re on deadline with an editor back at home office. The loneliness can eat away at you, and there’s always the danger. I’ve sat under indiscriminate shell fire and sweated it out at rebel checkpoints. In the opening days of the Rwanda genocide, a Hutu militiaman held a machete to my neck, threatening to kill me.

The first time I headed to a war zone was 1990, when thousands of U.S. troops were amassing in Saudi Arabia to push Saddam Hussein’s military out of neighboring Kuwait. I stayed for seven months, watching the U.S.-led coalition build up the war machine while diplomacy ran its course. When the war finally began, we used to run up to the hotel rooftop in Riyadh to watch Scud missiles coming in from Iraq. I was on the Saudi side of the border, heading into Kuwait once it was liberated. I never got a sense of real fear and destruction.

My first true taste of conflict came a couple years later when I covered the Rwanda genocide. It was a brutal form of warfare, hundreds of thousands of people from the minority Tutsi tribe were killed with machetes. It hurt my soul to see what one human was capable of doing to another—it was pure butchery. It took me a very long time to get over the horror of Rwanda.

Why I Stayed

Jackie reporting on the massacre in Rwanda. Photo courtesy of Jackie Northam.

Despite this, I kept living and traveling the world, always feeling excited going into a country for the first time. There were a lot of adventures, much camaraderie, and plenty of history in the making. I was in the news business, so I wanted to be where things were happening, not sitting in an office on the other side of the world. There was a satisfaction being called upon to zoom off to some major event.

I also felt I had a responsibility to continue covering foreign stories, particularly where U.S. troops were involved. It was important to chart both military progress and how the country’s treasure in blood and money was being spent.

I lost several friends to war over the years. Most recently was David Gilkey, an NPR photographer with whom I had spent a fair amount of time in Afghanistan. That was where he died, after the convoy he was riding in came under attack. David’s death was tragic, and it reinforced my notion that the longer you keep doing this job, the greater the chances of being hurt or killed.

David’s death was tragic, and it reinforced my notion that the longer you keep doing this job, the greater the chances of being hurt or killed.

About four years ago, I began to feel saturated by all the turmoil, cruelty, and suffering that I had witnessed, and it became increasingly harder for me to cover some stories. I had been shuttling in and out of Afghanistan and Pakistan on reporting trips nearly every other month. The parts of these countries I was in could be pretty grim, and I worried constantly about being kidnapped. I would get home to Washington D.C. from an overseas trip and have to process everything I’d seen and done, but there were very few people with whom I could share my experiences. And before I knew it, I’d be back on a plane somewhere.

Why I Left

I struggled with the decision of whether I should put an end to my years of conflict reporting. I was mindful of the emotional toll my heavy travel schedule was taking, but part of me was loathe to give up the type of reporting that helped make my name. I worried everything I had done would be for naught. I wondered what to do with my bounty of experiences—all the crazy and colorful people I had met, the momentous events I’d covered, and the tragedies and close scrapes I’d lived through. Would I still be relevant, important to my company, if I hung up my traveling boots? Would I lose my identity?

My colleagues helped me recognize that I was trying to leave one life behind and create a new one.

My indecision went on for months. One Sunday morning I called a good friend in Vancouver, B.C. When she answered, I started crying. She had just gone through a very tough divorce and must have recognized the need for a good cry. She let me weep, uninterrupted, for a good long while. I had made a decision.

Maybe I should have gone to a therapist to help me through this, instead I turned to peers who had gone through this themselves. They helped me recognize that I was trying to leave one life behind and creating a new one. Most importantly, they reassured me that all my foreign experience wouldn’t be wasted, I would find new ways to use it. They told me to be patient.

Embracing a “Normal” Life

I talked to my foreign editor at the time, and she agreed to give me a bit of a break from the road, as long as no major news story happened overseas. For the first time in years, I was able to make commitments without the usual caveat of “unless I’m overseas.” It was springtime, so I found a tennis coach and joined a rowing club. I stopped worrying every time the phone rang that I would be called away. It took a while to adjust to my new life, but in time I felt more settled and happy. Finally, after 30 years of waiting, I was able to adopt a dog.

Finally, after 30 years of waiting, I was able to adopt a dog.

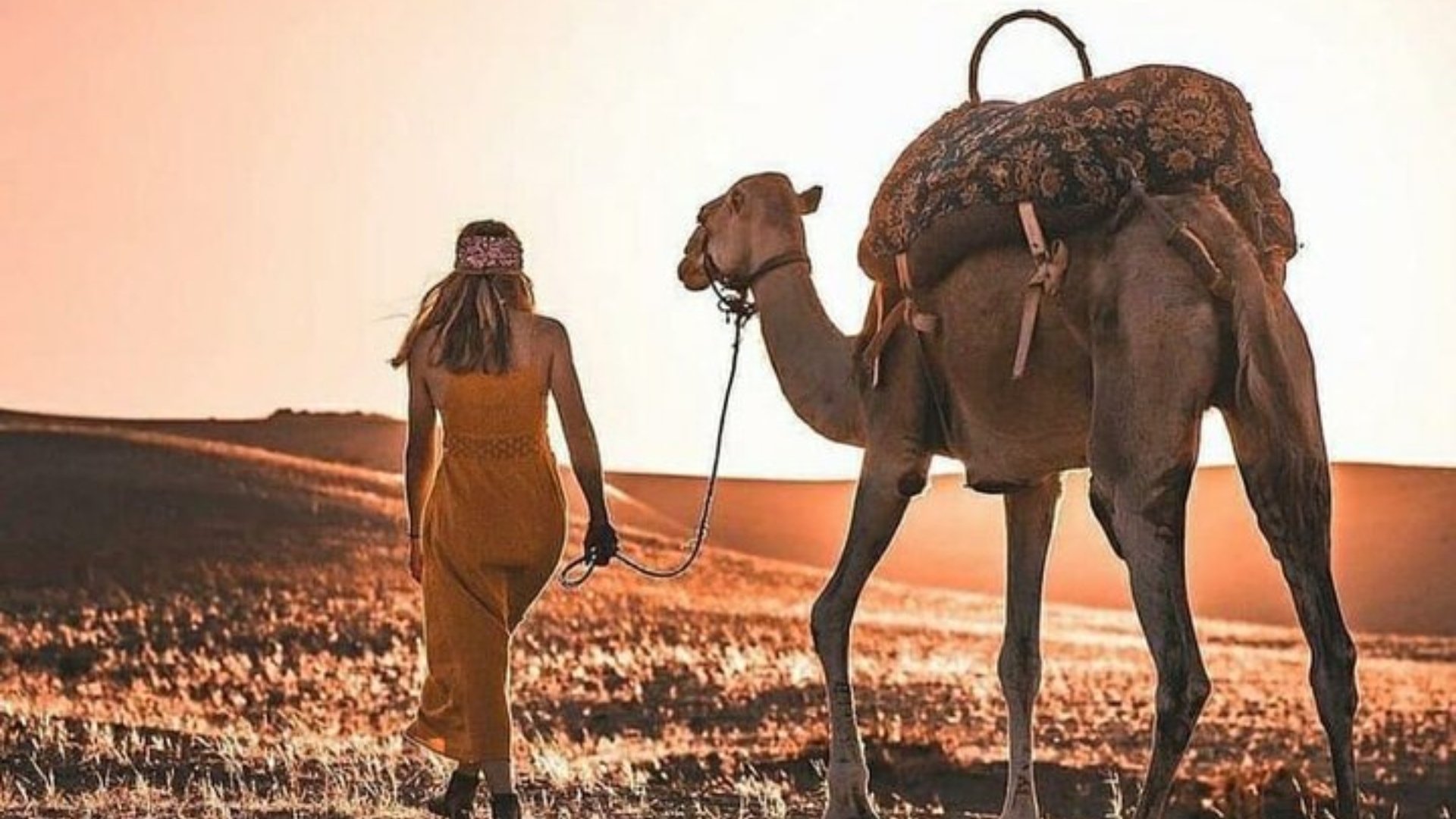

My foreign editor worked with me to develop a new “beat.” I became an International Affairs correspondent for NPR, which allows me to cover a wide range of foreign news stories. I have a lot of latitude about when and where I travel for stories. My most recent reporting trip took me to Saudi Arabia to chart all the changes going on in the kingdom under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the man U.S. intelligence officials have concluded was involved in the death of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

I watch as younger colleagues go off into conflict zones now, and I wish them much luck and success. I had an amazing run at it and wouldn’t have changed a thing. I grieved when Marie Colvin lost her life in Syria covering stories that were important to her, and I am pleased her memory lives on in books and a movie. Her death also made me realize how fortunate I was to have dodged the same fate during my career, making me all the more grateful for the life I’ve found away from the danger.

***

Jackie Northam is NPR’s International Affairs Correspondent. She is a veteran journalist who has spent three decades reporting on conflict, politics, and life across the globe—from the mountains of Afghanistan and the desert sands of Saudi Arabia, to the gritty prison camp at Guantanamo Bay and the pristine beauty of the Arctic. Northam has received multiple journalism awards during her career, including Associated Press awards and regional Edward R. Murrow awards, and was part of an NPR team of journalists who won an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award for “The DNA Files,” a series about the science of genetics. A native of Canada, Northam spends her time off crewing in the summer, on the ski hills in the winter, and on long walks year-round with her beloved beagle, Tara.

0 Comments