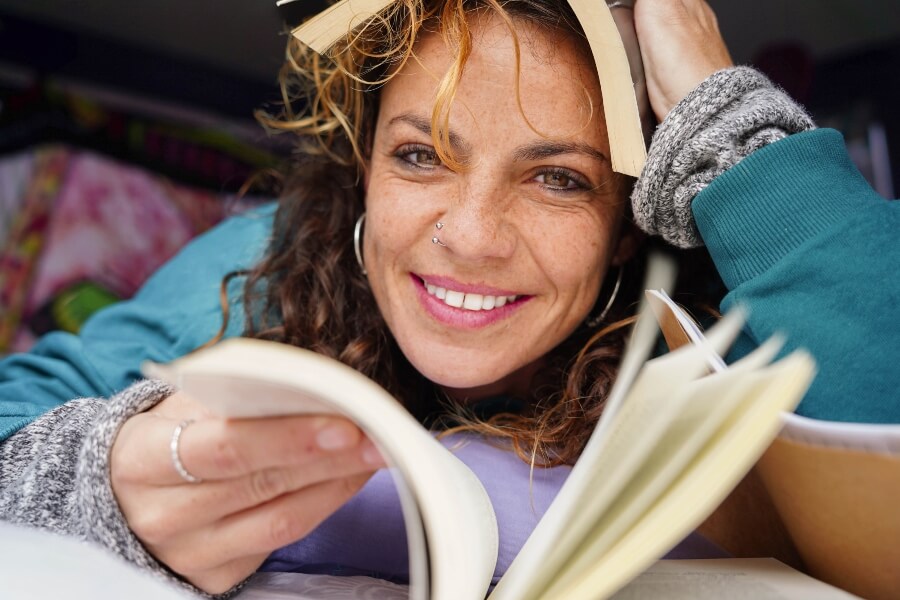

If Jennifer Clement were just an author, her career would be awe-worthy enough. Critics have called her writing “beguiling,” “mesmerizing,” “crazily enchanting,” and “luminous.” Her most famous book, the lyrical, dream-like Prayers for the Stolen, follows Mexican mothers and daughters terrorized by the drug trade and has won numerous literary awards. Her 2018 novel Gun Love is about gun violence in the U.S. and gun trafficking into Mexico. This story of a mother and daughter swept up in brutality was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, is A New York Times Editor’s Choice and one of Time‘s 10 Best Fiction Books of 2018.

But Jennifer Clement is not just an author. In 2015, she was elected the first female president of PEN International, the prestigious literary organization focused on defending freedom of expression. Members include the likes of Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, and Salman Rushdie. Now she spends most of her time fighting against “censorship by the bullet” and political propaganda as well as promoting the work of female writers and women’s access to literature around the world. Born in the U.S. and raised in Mexico, Clement has been shaped by the vibrancy and heartbreak of Mexican culture.

But Jennifer Clement is not just an author. In 2015, she was elected the first female president of PEN International, the prestigious literary organization focused on defending freedom of expression. Members include the likes of Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, and Salman Rushdie. Now she spends most of her time fighting against “censorship by the bullet” and political propaganda as well as promoting the work of female writers and women’s access to literature around the world. Born in the U.S. and raised in Mexico, Clement has been shaped by the vibrancy and heartbreak of Mexican culture.

What do you consider your first breakthrough as a writer?

It was my very first poem accepted and published by the Gallatin Review, a literary magazine at NYU. I never get used to the true wonder that someone wants to read my work.

Your work focuses on human rights. What brought you to that topic?

I didn’t even realize it until I’d written enough books to look back on what I was doing. It wasn’t with conscious intent. Now I know I write about what hurts me and about the unprotected and how the powerless exercise power.

Can you describe the research you did for Prayers for the Stolen? Did you ever feel in danger while doing your research?

I think of my novel Prayers for the Stolen as a requiem for Mexico. For over ten years I interviewed, although I prefer to call it listening, to women who had been victims of Mexico’s violence due to the government’s declared “war” against the drugs cartels. I wanted to explore how violence in Mexico was affecting women as there was very little attention being paid to this both in the news and in literature (but now in Mexico we have an actual genre we call Narco Literature).

The book has a chilling subject matter, but yet was written with humor and joy. Charles Dickens called this kind of writing—a mix of tragedy and humor—“streaky bacon,” which is the way he wrote his classic novels that are filled with social criticism.

Prayers for the Stolen is placed in the state of Guerrero because it is the land where poppies are being cultivated and where most of Mexico’s heroin, known as Black Tar on the streets of the U.S., is produced to satisfy the huge demand north of the border. Mostly everything in the book is fiction. The only character based on a real person is the collage teacher in the women’s jail in Mexico City. Although the subject matter is important to me, of course, I am most interested in craft. I never cease to think about the language I am using, the form, plot structure, character development, and voice. Even in doing the research for Prayers for the Stolen, I was also always looking for the poetic experience. I also wanted the novel to have enchantment.

The publicist at Penguin Random House had to try and figure out how to sell a book that was about such chilling subject matter, but yet was written with humor and joy. Charles Dickens called this kind of writing—a mix of tragedy and humor—“streaky bacon,” which is the way he wrote his classic novels that are filled with social criticism.

What do you think the impact of the book has been on the lives of women affected by the drug trade?

I think it has not had any impact for social change. But there is greater awareness thanks to the book. Every single Mexican who reads it tells me they had no idea this was happening.

As president of PEN Mexico, you worked to protect journalists. How dire is the situation for journalists in Mexico?

As president of PEN Mexico, I had to focus on the killing of journalists—what I came to call “censorship by bullet”—and also the consequence of fear, which produces self-censorship. Although my work interviewing women who had been victims of Mexico’s violence required me to be vigilant of my safety, the most dangerous work over this time was my PEN work that concentrated on bringing global attention to the problem.

Although my work interviewing women who had been victims of Mexico’s violence required me to be vigilant of my safety, the most dangerous work over this time was my PEN work that concentrated on bringing global attention to the problem.

In Mexico, there’s not a single person in jail for having killed a journalist, and there are vast areas of the country where there’s no reporting at all and so we have no idea what is happening. If a country does not have a free press it cannot have a democracy. What I came to understand is that a journalist is a very dangerous person. Criminals and corrupt politicians are scared of journalists, but they are not scared of novelists or poets, and they are never afraid of teenage girls and grieving mothers.

What is the significance of being the first woman to head Pen International? What issues are you pressing that haven’t been a priority earlier?

Clement with the Dalai Lama this spring while working to help writers in exile from Tibet.

As the first woman president, I feel a great responsibility to address the censorship of women across the globe, to change PEN and bring the problems that women and girls face into the central part of my work. I mention girls because if you cannot learn to read and write, you’ll never be a writer.

I have begun at the very core of the organization’s very ideology by trying to change the PEN Charter. At present Article 3 reads:

Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world.

As the first woman president, I feel a great responsibility to address the censorship of women across the globe.

Article 3 was a product of the early 20th Century and has lasted unchanged for some 90 years. Today we need to bring in our current debate of gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, and other categories of identity. I’d like to change the Charter to include all hatreds and bring in the concept of equality. This will be presented for vote at our annual PEN congress in September, which will be held in Ukraine.

I am also going to implement the PEN/VIDA Count in all 150 PEN centers across the globe. The Vida Count is way to tabulate how women writers are marginalized. It keeps track of how many women win prizes and are reviewed – which are the ways that writers become prestigious.

The Vida Count discovered that women were not being reviewed or winning prizes. It also revealed subtle discriminations.

The Vida Count discovered that women were not being reviewed or winning prizes. It also revealed subtle discriminations. For example, women are almost always reviewed by women and their work is compared to the writing of other women. Also the women’s books that were nominated for prizes or won prizes, invariably their protagonist was a male.

Here are a few examples of the 2015 Vida Count:

- The Booker: women have won 17 times in 45 years.

- The Pulitzer for Fiction: women have won 18 times in 67 years. (No woman protagonist has been in a winning book in the last 15 years.)

- The PEN/Faulkner: women have won 8 times in 33 years.

We are in a time when some consider truth fungible. Do you think alternative facts and fake news should be protected under freedom of expression?

In PEN we defend freedom of expression but we also know that truth is not fungible and that propaganda is dangerous. In these times, and as President of PEN, it is impossible not to reflect on the rise of propaganda and its relationship to freedom of expression and truth—from Russia, to the Islamic State, to the debate around Brexit, and, most recently, in the elections in the United States. Propaganda is antithetical to the free flow of ideas and is closely linked to xenophobia and religious and ethnic intolerance across all continents: the refusal of Australia to allow asylum seekers access; the plight of the Rohingya; inter-ethnic conflict in Mali; and the devastating wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

In these times, and as President of PEN, it is impossible not to reflect on the rise of propaganda and its relationship to freedom of expression and truth.

Such hatreds spawn censorship in law and practice, engender self-censorship, and can lead to the ultimate loss of freedom of expression when poisoned words turn to physical attacks and even the murder of those whose writings were not to the liking of another. Where impunity for such attacks prevails, such as in my own country of Mexico, the space for dialogue to create mutual respect and understanding shrinks ever smaller.

At the heart of PEN’s mission lies the transformative power of literature and the written word to promote peaceful debate and dialogue. PEN’s members have been reclaiming truth from propaganda since 1921. As a reflection of our times, our congress in the Ukraine in September will be about truth versus propaganda.

Where do writers face the biggest threats and how can PEN help them?

We have many programs and committees, but our most central work is helping writers in prison and writers in exile. Sadly, there are problems of freedom of expression all over the world. At present, and when I say at present I literally mean this month, we are concentrated on writers imprisoned in Turkey and writers in exile from Tibet. I am actually answering these questions from Dharamsala, India.

In the U.S., how should journalists deal with the hostile environment for news and truth created by the Trump Administration?

I don’t have the answer except to urge them to continue to honor truth. I can share with you here the body of a recent letter from the Mexican PEN centers and signed by over 200 Mexican intellectuals to their colleagues in the U.S.

“You have stood with us during the darkest hours of press freedom in Mexico and, although we never could believe this day would come, we now stand with you.”

At this time of an unprecedented, relentless assault on the free press of the United States by the Trump administration, we journalists, writers, and publishers in Mexico stand in solidarity with you as you do your crucial work.

For decades you have stood by us as successive governments and criminal gangs have targeted our press and assassinated our journalists for doing work in the public interest uncovering crimes and corruption. And so many times we have only known the truth about our own country by reading the stories followed and uncovered in the US press. We urge you to continue to uphold freedom of expression as your society, institutions, and values depend upon it.

You have stood with us during the darkest hours of press freedom in Mexico and, although we never could believe this day would come, we now stand with you.

A version of this article was originally published in May 2017.

0 Comments