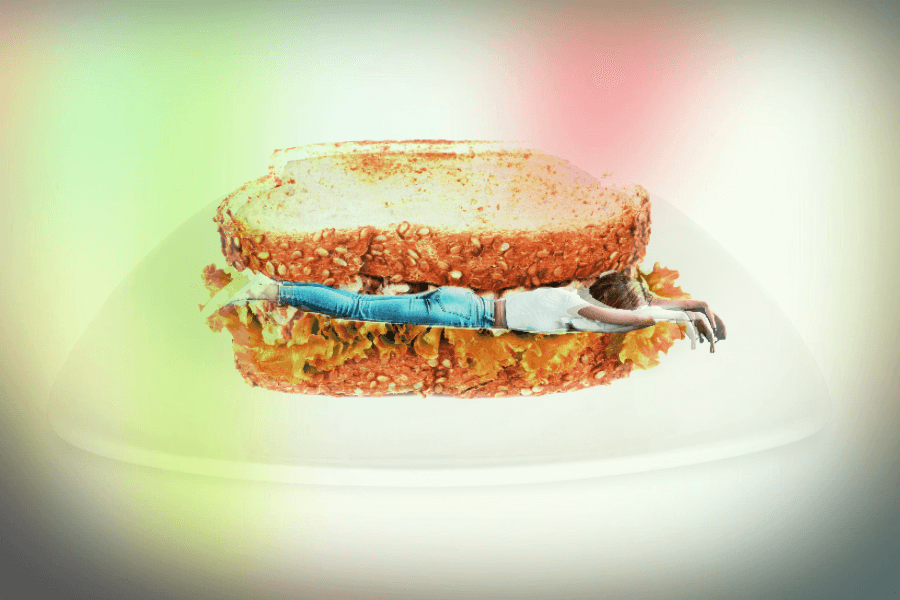

Usually, when women our age are referred to as “the sandwich generation,” it’s because on one piece of bread we’re raising needy teenagers or college students, and on the other slice we’re caring for needy, maybe sick parents. And here we are, stuck in the middle of everyone. But there’s another, less discussed sammie—the one in the office.

The office sandwich finds the middle-aged woman playing the role of egg salad between 20-something millennials and 60-something baby-boomers. In my case, I supervise a 25-year-old millennial—let’s call her Madison—and I report to a 65-year-old man we’ll call Jim. In my mid-40s, I’m squarely in the middle, both in terms of age and rank.

The Millenial

Madison is sweet, super-smart, and a typical millennial, was raised exquisitely. Her parents lavished love and support on her, prioritized her education, made sure she was well-rounded, and instilled in her a strong sense of civic responsibility.

She was raised exquisitely and her childhood was infused with the rhetoric of Hope and Change.

Her parents raised her in much the same way I’m raising my own children. But there’s one big difference between Madison’s millennial mindset and the Generation Z mindset: her childhood was infused with the rhetoric of Hope and Change, and my teenagers have come of age in the Huckster-in-Chief Era. Naturally, one of these generations is a lot more cynical than the other, and it’s not the millennials.

I see Madison working hard to believe that her work is meaningful. Like so many other millennials, she’ll pipe up during a conference call and say something like, “This is really exciting!”—and she’s talking about a re-tweet. While discussing a report, let’s say 40 soporific pages of 10-point type that reads like a term paper, she’ll say something like, “This is going to be a game-changer.” She believes in her power to make the world a better place and that this power is derived from her paid office job.

The Boss

And then there’s my baby-boomer boss. He’s been around the block a few decades, and he knows that no tweet, even a re-tweet by a B-list celebrity, has ever changed anything—or ever will. No conference call, no partnership, no campaign, no single white paper will be a game-changer. He knows that change is incremental, that the world works in slow and gradual ways, and that degrees from prestigious universities don’t amount to much in the universe of getting-things-done.

He knows that change is incremental, that the world works in slow and gradual ways.

I’m comfortable in the middle of these opposing philosophies. Like Madison, I want to try sometimes to believe that what I do matters. But I also know that Jim is right, that change happens at a glacial pace. Where things get most uncomfortable is that tender spot where Madison and Jim intersect—a meeting.

Meeting in the Middle

In meetings, Madison speaks up, uninvited and unprompted. After all, she’s been taught her whole life that her voice matters, so of course she will be the first person to speak or the person to speak the longest. Or both. “Use your words,” we’ve said to our children for years. So they do. Madison knows her opinion is important!

But as she’s talking, I see Jim’s head start to explode.

But as she’s talking, I see Jim’s head start to explode. To him, she seems presumptuous, arrogant. There are older, more experienced people at the table, and Jim would prefer to hear from them first and in more depth. There’s an opportunity cost with Madison using so much air time: the longer she talks, the less we get to hear from others. Plus, there is a respect issue: Jim was raised to wait.

There’s also the issue of self-promotion. Madison advocates for herself, and as a woman who’s been in the workplace a long time, I admire the vigor with which she tells the room what she’s accomplishing and why we should be impressed. But her desire to advocate for herself is perhaps too palpable, certainly for Jim.

His position is that a person shouldn’t need to brag about doing a good job, shouldn’t need public recognition. What happened to the days when you just did a good job because you took pride in your work, he’ll ask? I don’t even tell Jim about the one-on-one conversations I have with Madison in which it’s clear that she needs me to tell her she’s doing a great job. It’s as if she can’t quite breathe until she hears those words—“fantastic job”—issuing forth from my lips.

The Struggle of the Young

Sometimes meetings are rocky from the get-go. Jim likes to start meetings with personal check-ins, asking everyone, “How was your weekend?” or “How’s your day going?” After about five or 10 minutes of this, I can see the impatience hovering above Madison’s head like a giant cartoon ball of steam. Or perhaps an older colleague will spend a few minutes to share a work story from the old days, and that’s when the millennial eyes really roll.

They’re reaching for their phones so they can maybe get some work done.

For the older employees, sharing a story is part of the maintenance of company lore, upkeep on the fabric that holds together everyone in the room. To millennials, it’s a poor use of time. They’re predisposed to dislike meetings to begin with; add on 10 minutes of unproductive chit-chat, and they start to reach for their phones.

But I want to be fair: millennials are not just reaching for their phones because they’re bored hearing about their colleagues’ weekends. They’re reaching for their phones so they can maybe get some work done. They are, after all, underpaid and overworked, just like we were when we were in our 20s. But possibly it’s even worse for them than it was for us.

They have so much work piled onto them, and let’s face it, we’re living in a gig economy like we’ve never seen in our lifetimes. In a gig economy time is literally money: you get paid for tasks completed, and then you walk away, move on to the next task.

A Different World

I don’t think Jim understands the pressures Madison faces as a result of the gig economy. He’s spent most of his career in a golden age of work. He actually has a pension from a previous job. A pension, I said! He will start collecting social security soon, as will his wife. He may even retire to another part of the country, in a home he owns, not dependent on anyone else to support him. Is this kind of independent retirement an option for Madison? For my children? For me? Maybe not.

Is this kind of independent retirement an option for Madison? For my children? For me? Maybe not.

The other benefit Jim experienced in the golden age of work was a culture of investing in relationships. He puts his faith in people. His bosses cared about him, truly and personally. And he cares about his protégés, truly and personally. When I told him my mother was very ill, he asked every day how she was doing. He elevates interpersonal skills in the workplace and puts a premium on solidarity. But these are the workplace luxuries available to employees who can afford to stay in one job for years or decades at a time instead of having to constantly search for a new job just to get a raise.

Jim once said to me, when complaining about Madison’s self-advocacy, “there’s no ‘I’ in team.” Well, I explained, that’s true, but there’s no team anymore. At least not from her point of view.

Working With Millenials: Bridging the Divide

But there’s something Madison doesn’t understand about Jim: the men and women of his generation genuinely care. For years he turned a blind eye when I had to leave work early to pick up a sick child from school or go to a parent-teacher conference. I’ve seen him champion colleagues and urge for their promotions. He knows that people are not robots, that people should not be reduced to a set of outputs.

But that’s exactly what it feels like to Madison, I’m sure: she is the sum of her outputs, increasingly paid not for teamwork but for piecework. Like ladies who sewed gentlemen’s shirts in their kitchens while the soup was boiling, the millennials are trying to mastermind their own enterprises. No matter how nice the chit-chat might be, who the hell has time for it?

So what’s a boomer like Jim to do? I say, have compassion. These kids’ futures are a lot more uncertain than yours was. What they’ll have to contend with, in the wake of environmental degradation and an ever-stratifying caste system, is unknowable. And scary.

So how about this? When the meeting starts, ask if anyone needs to leave early because of pressing deadlines, and let them talk first. Or find something to praise about her before she feels the need to self-promote. If you’re the one contributing to the overwork, lay off a little. And buy her a coffee, maybe?

And what’s a millennial like Madison to do? Again, I say, have compassion. The Jims of the world do care about you—it’s not an act. Throw them a bone, tell a cute story from your weekend or ask about their weekend. Also maybe worry a little less about your outputs, and save the self-advocacy for the annual review. And buy him a coffee, maybe?

A version of this story was originally published in May 2018.

0 Comments