Editor’s Note: Through March, which is women’s history month, we’ll be publishing stories about women who have been underestimated, erased or simply overlooked. Faith Ringgold is a major force in the art world who should be a household name.

***

“You can’t sit around and wait for somebody to say who you are. You need to write it and paint it and do it.” Those are words to live by from artist, writer, activist and teacher Faith Ringgold, who embraces that ethos and is going strong at age 91.

NextTribe was fortunate enough to have an exclusive interview with her while she’s having what one might call “a moment.” This fall, many previously unseen works from the 1970s were shown at the ACA Galleries in Chelsea, Manhattan, demonstrating why she was both an innovator and an instigator.

On view is the clear interrelationship between Ringgold’s personal narrative, her political engagement, and her role in both the African-American and feminist movements. In addition to the gallery installation, Ringgold is represented in several top traveling shows including, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (1963-1983). Upcoming in 2019 is the traveling exhibition organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, ONE THING: VIET-NAM, Art and America’s War, 1965 to 1975.

Decades of Dedication

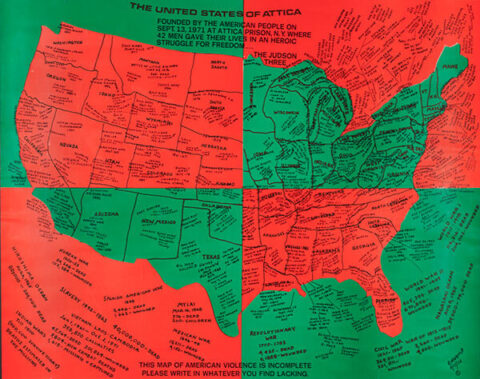

United States of Attica by Faith Ringgold. Image: ACA Galleries

This acclaim for Ringgold marks a fresh appreciation for her pioneering work. Ringgold studied art education at the City College of New York at a time when women were denied admission to the art department. Undeterred, Ringgold earned a BS in Fine Art and Education in 1955. Four years later, she completed an MA in Art. At that time, she was also a mother to two young daughters.

Early on, Ringgold was mixing imagery and text to explore national and cultural references. During the explosive 1960s, she tackled the incendiary issues that were inflaming the country in her searing series, The American People.

During a 1968 Whitney exhibition of American sculptors of the 1930s, Ringgold was the force behind a demonstration at the museum. It called out the institution for not including any black artists. In 1970, Ringgold returned to the barricades as a member of the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee, this time to push back on the paucity of female artists in the Whitney Annual. (Check out the tone of this New York Times article on the event.)

Ringgold tackled the incendiary issues that were inflaming the country.

Unfailingly, Ringgold originated her own world and then invited others in. Within a gallery setting, the soft sculptures, thangkas, and mixed-media pieces take on a more formal quality,yet the energy that emanates from them is palpable. The political posters could be viewed as historical documents from decades ago—if they weren’t so painfully relevant to the landscape confronting America right now.

The United States of Attica, one of Ringgold’s most extensively disseminated posters of the period, references the innumerable acts of violence that have occurred during America’s history: assassinations, lynchings, and repeated episodes of genocide against the indigenous nations. At the bottom is the declaration: “THIS MAP OF AMERICAN VIOLENCE IS INCOMPLETE. PLEASE WRITE IN WHATEVER YOU FIND LACKING.”

It was hard not to shudder while thinking of the countless mass shootings and murders of unarmed black people that have since occurred, proving the resonance and relevance of her work.

Face to Face with Faith

Turn Within #2 by Faith Ringgold. Image: ACA Galleries

I was able to sit down with Ringgold on a recent Saturday while she was on-site at the gallery. She entered the space looking like she had stepped out of one of her pieces. She was wearing red sequined boots, a green mesh hat, and color-matched earrings, plus a Moroccan necklace, beaded bag, and a jacket trimmed with stitching.

“I’m telling my story,” Ringgold said. “The things in life that are the most important to me become my art. It inspires me, and I hope it will inspire others.”

I decided I wouldn’t try to please others.

We discussed the limits of the “art establishment,” specifically during the 1970s. “The art world was not into political art when I was. Many artists worried about having unpopular opinions. I decided I wouldn’t try to please others. I would paint it the way I see it.”

Ringgold, who suffers from asthma, needed to find a way to fulfill her desire to do three-dimensional work. Stone, clay, and wood would be harmful to her health. Ringgold’s mother, a fashion designer, taught taught her to, which made fabric a natural choice.

Traveling to Find Inspiration

Visiting Africa had a tremendous impact on Ringgold. Influenced by the masks of the Dan people of Liberia, Ringgold digested what she had seen and then added it into her own vocabulary. “I was amazed by the masks and the dolls and the performances. I came home very inspired,” she told me.

You need strength and perseverance to create what is worth seeing.

Despite the 1970’s feminist art movement and the incorporation of what had previously been categorized as “craft” materials, there remained a tendency by the predominantly male art “taste-markers” to resist these forms of expression.

“It doesn’t matter what other people think,” Ringgold stated evenly. “It’s very hard, but there’s really no choice. We don’t all see the same things.” Reflecting on the obstacles she surmounted, Ringgold admitted, “You need strength and perseverance to continue and to create what is worth seeing.” Pausing, she noted, “Make sure that you love it. That’s the key.”

Finding Your Voice, Staying Very Visible

Family of Women Series by Faith Ringgold. Image: ACA Galleries

It was inevitable that our talk would veer to the current challenges facing America. “We have a history of struggles,” Ringgold underscored. “You can’t eliminate that. When you have a democratic country, you are going to have some bad people. You can’t remain free without some negativity. But,” she emphasized, “people can’t sit quietly by.” Ringgold began a sentence, “As long as you have freedom of speech …” then trailed off. She followed up with, “You can’t have art if you don’t have freedom of speech.”

Her thoughts turned to the 2016 election. “They didn’t want a woman. I’m sure of it. I’d love to see a woman president in the United States, but the country walked away from it,” she said.

I asked Ringgold why she thought so many women begin to feel invisible as they get older. She wasn’t having it.

“Speak up! Do something to maintain your visibility in your way. Make your presence obvious. Don’t allow that to happen to you at any age! There are ways to express your ideas,” Ringgold insisted. “No one has the right to take power over another. We have work to do.”

***

Marcia G. Yerman, based in New York City, writes profiles, interviews, essays, and articles focusing on women’s issues, human rights, the environment, politics, culture and the arts. Her work has been published by the New York Times, truthout, AlterNet, The Raw Story, Women News Network, and The Women’s Media Center. Her articles are archived at mgyerman.com. You can find her on Twitter @mgyerman.

Feature image of Faith Ringgold above was taken by Marcia G. Yerman.

0 Comments