“Saying `Three thousand people died sounds so impersonal and distant,'” said the rabbi who officiated at the first memorial service, shortly after September 11, 2001. It was held at a stadium; I avidly watched it on TV. “Rather,” he went on, “I think of it as: `One person died, three thousand times.’”

I may have mangled the precise adjectives he used between the two sets of internal quotes, but the quotes themselves I have never forgotten. Imagine one person again and again and again and again and again.

No national horror has ever been as painful to me, however, in their different ways, the Kennedy assassinations (both President John’s and Presidential candidate Robert’s) and the Sandy Hook assassinations of young school children come close. Planes full of happily traveling people, highjacked by suicidal/homicidal haters into towers full of happily working people ! Staring up and watching the unbelievable carnage, live, from my close-to-downtown Greenwich Village neighborhood— crowds forming in the streets: It felt like a never-expected form of the end of the world.

I had the privilege of getting to know, at least briefly, the families of 80 victims through articles I wrote on the first, fifth and tenth anniversaries of that holocaust. It was overwhelmingly moving to consider the youth of so many of the people who died in the Twin Towers, and the heartfulness and insistent positivity of their families in creating foundations in their loved ones’ names.

Read More: For Gabby Giffords, a Terrible Reminder of Her Ordeal 10 Years Later

The Sisters Jackman

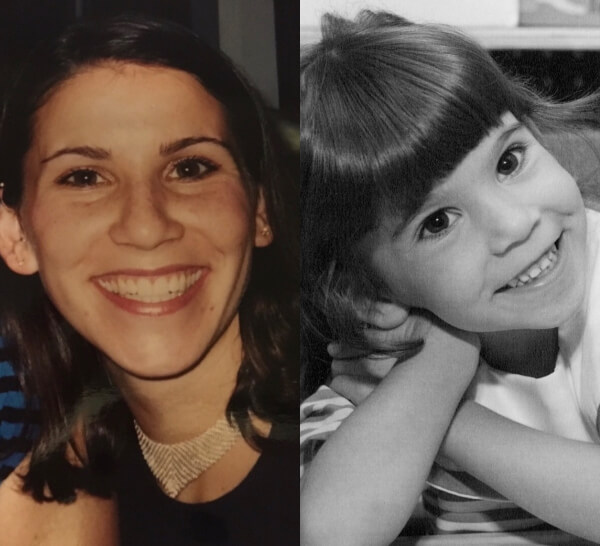

It just happened that I kept in touch with one of the families over the years. Like the rabbi said, the resonance of one person dying often stays beating in our heart and we continue to go there. In this case, it’s a sister story. Erin Jackman is 50 now; her adored sister Brooke, who died when she’d just turned 23, would be 44 today, had she lived.

Erin remembers how tiny Brooke had once seemed to her. “I would dress her up like a doll” when she was a baby, she recalled to me when we first spoke. “Then she was my little sister,” tagging along, “calling out, `Wait for me…!’” But as the girls grew up in Oyster Bay, New York, their age difference became less of an issue. “Some sisters just have that `sister thing’—that instinctive closeness. We had it, and we knew it.”

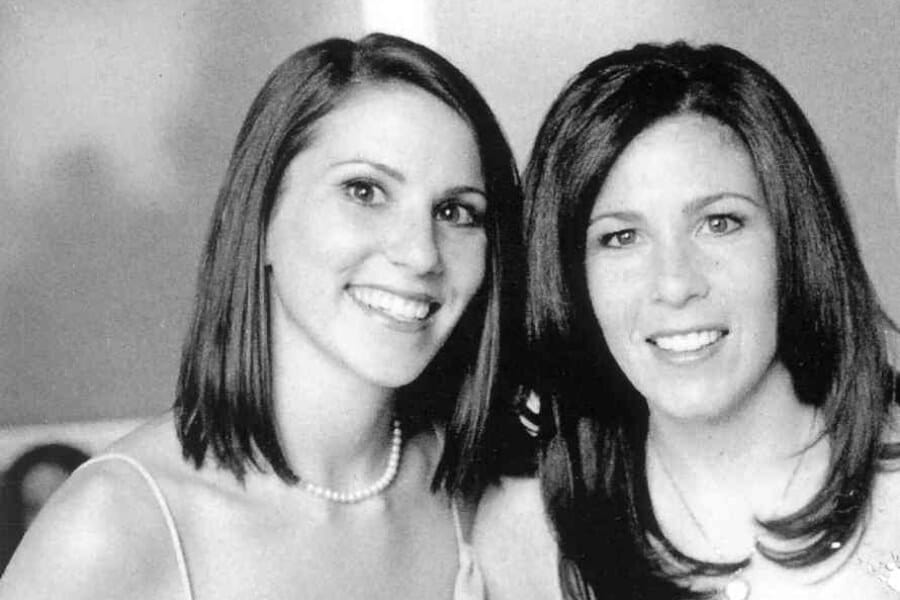

Even when they were young adults, they remained close—Erin leaned on Brooke for her younger sister’s savviness with a computer (this was in the most tech-innocent days) and her riskier sense of style. Brooke counted on Erin’s career advice and the overall benefits of her maturity. They both chose teaching as a profession and moved to Manhattan, although they kept separate apartments.

Every Saturday they would get facials and then walk the city, “arm in arm, shoulder to shoulder, for hours.” On Saturday September 8, 2001— to help Brooke over her breakup with a boyfriend, “we took the Randy Walk,” Erin recalled. “We went to all the places they went together, as a kind of good-riddance rite of passage.” The sisters always hugged before going home, “but this day, we left without the usual hug, then simultaneously realized it and started back toward each other. But we got lazy and waved and laughed, `See you later!'” So many laters would there be— of course.

The last time Erin saw her sister, they parted without their usual hug.

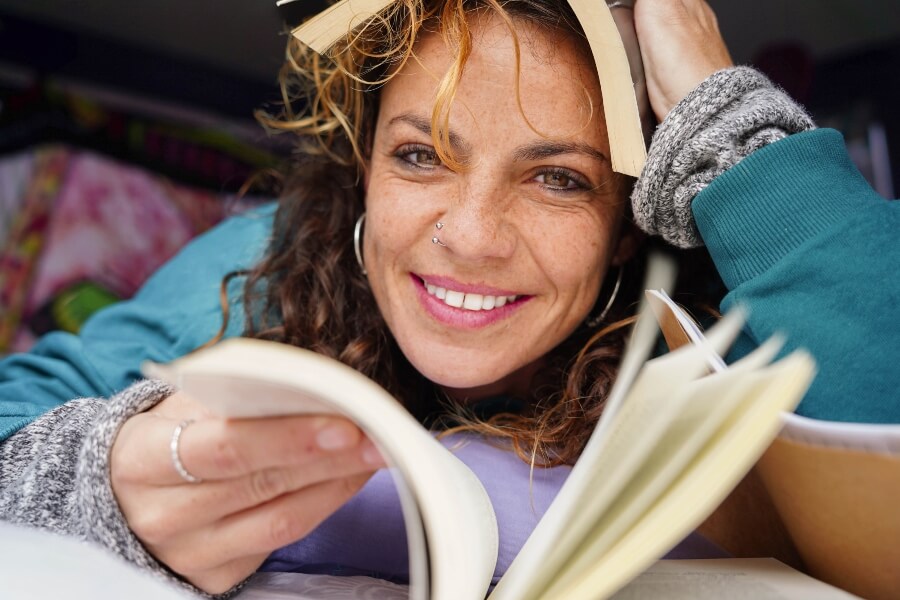

More than anything else, Brooke Jackman was a vibrant idealist. The short end-of-summer job she had taken at the financial services firm Cantor Fitzgerald at the top of One World Trade Center was as temporary as could be. She couldn’t wait to start classes at UC Berkeley’s graduate school of social work, and after that to help underserved children. As a girl, she had worked at a soup kitchen and volunteered at a school for children with disabilities. And she loved reading—always a book on the subway, always a book in bed.

Two days after Brooke and Erin took their “sister walk,” on September 10, 2001, Brooke called their mother about the upcoming Jewish holidays. There was much else to celebrate: Brooke‘s and Erin’s recent birthdays, and their father’s end of chemotherapy for lung cancer. She would come and help mom prepare for Rosh Hashanah, she said. She told her mom how happy she was to be finishing the brisk summer job at Cantor Fitzgerald and flying cross country to start her real career, stressing: “There’s more to life than money.”

The Most Awful Day

The next day—that beautiful, cloudless, humidity-free Tuesday New York morning: the 11th— Erin was in her downtown New York classroom when “some of the parents came to school in a panic,” telling everyone that the two towers of the World Trade Center had been—what?!—intentionally hit by planes. Everyone thought the first hit was a terrible accident; the second hit proved the unthinkable.

Heart in her throat, Erin ran to the nearby Wall Street office of their father. Everywhere people were running and there was smoke in the air—not normal smoke, somehow-worse smoke. “There were no words” for what had happened, she knew.

Of course she ran down the thousands of stairs and is okay…somewhere, if only we can find her!

For two days Erin and the family refused to give up hope, even though hospital after hospital showed at-the-ready ER teams and set-to-go ambulances…with no patients for these services. Brooke is so young and vital! Erin thought, despite all signs to the contray. Of course she ran down the thousands of stairs and is okay…somewhere, if only we can find her!

This was pre-social media. Communication was via day and night radio and network TV. Cell phone service went out due to too much use amid insufficient technology; people jammed quarters into the still plentiful pay phones; families plastered HAVE YOU SEEN HER/HIM? posters of their handsome and comely and eager-faced young finance workers on hospital walls.) We neighbors dutifully stood in long lines to donate blood—but no one was alive to need it. (We soon switched to donating shoes and clothes to the workers.)

Then Mayor Rudy Giuliani (why couldn’t he have stayed this truly decent and leaderly?) gathered the Cantor Fitzgerald families together and solemnly said, “No survivors” (658 members of the company: dead!). Erin and her family—now powerless in the face of the unavoidable truth—arranged a candlelight vigil for Brooke at Brooke’s favorite book store and “over a thousand people came to pray,” she recalls.

Never Forgetting

Then Erin did two things. She vowed she would never forget the sound of Brooke’s voice or the “Brooke look” of her sister, which Erin identified as: a skinny top with wide-legged pants). And she and her family formed the Brooke Jackman Foundation. They determined that Brooke’s desire to help underserved children—to teach them to read, quest and thrive—dare not be lost and that, in Brooke’s honor, that mission would grow.

At today’s 9/11 memorial service, Erin’s 17-year-old niece will read the name of the aunt she never met.

Erin threw herself into the foundation and has worked on it continually since. “We started with ten families and it’s grown and grown and grown,” she says. Partnerships with social service organizations, corporate philanthropies, and Scholastic Magazine’s literacy partnership as well as a yearly gala have helped it thrive.

Starting with the distribution to 100 children in two shelters, the foundation has, since 2002, given away more than 100,000 Brooke BackPacks—stuffed with school supplies and books—to children in various places across the country (and sometimes elsewhere—including to children in Haiti during the 2010 earthquake).

When I talked, the other day, to an over-busy Erin (her five-year-old son was starting preschool this year), she and her husband were driving through Manhattan (they live in Florida) on foundation business. She told me she had just sent off 5,000 Brooke BackPacks for the school year.

The pandemic was tougher for underserved families than others, of course. “They were hit hardest, and lots of them were naturally more concerned with putting food on the table than anything else,” she says. “They were already struggling and then there was COVID, and they had less access to online opportunities and they fell further behind. We met them where they were—hybrid online and in-person groups.” The foundation launched Brooke’s Cooks, helping families pair a love for learning with education on, and preparation of, healthy foods. “I didn’t think our programs would work online, but they did. And the feedback we got—people were thankful that somebody cared.”

Yesterday, on September 10th, the Brooke Jackman Read-A-Thon” (a marathon read-aloud event) took place at a Barnes and Noble in Tribeca, near the 9/11 memorial. The readers included local performers, and the event “feels like an important act—to remember Brooke and September 11, in a positive, meaningful way,” Erin says. Visiting Brooke’s plaque at the memorial and listening to all 2,977 of the victims’ names read will be another part of today. Erin’s 17-year-old niece will read the name of the aunt she never met.

A House in the Clouds

“I can’t believe it’s been 21 years—and she was only 23,” Erin muses, emotionally. “Back then, it was unimaginable that I could make it through a day, make it through a week. I couldn’t imagine going on, living without her physical presence.” One person dies three thousand times, indeed.

I’m proudest that we did what she didn’t get the chance to do.

“It’s hard with my son, Ryan Jack,” Erin says. “He knows Aunt Brooke is in heaven. Her birthday was two weeks ago and we sent balloons up to her in the sky. He doesn’t understand yet. When we flew to New York [from Florida] the other day, he looked out the plane window and said he was looking for Aunt Brooke’s house in the clouds.

He has come every year to the memorial on 9/11 as well. But my husband and I aren’t ready for the big conversation yet about 9/11.”

When I ask her what she is proudest of, she doesn’t hesitate. “I’m proudest that we really did the foundation. That we kept her dreams alive, that we did what she didn’t get the chance to do. I love hearing directly from the children and families that we serve about why these programs are so vital to them.”

But gratification is bigger than pride—and it is her promise to herself about Brooke that keeps her going through the everyday business of life and through milestones they’ve missed. The birth of her child. Perhaps the discovery of a first gray hair. “I used to worry that I’d forget the sound of her voice. But I haven’t! I hear her in my head. Her laugh. How she’d call me `Errie.’ And how she’d ask me, `Is that really necessary ?!’ and laugh.”

“She is really with me, every day.”

Thank you, Erin, for your lesson in true and abiding sisterhood.

0 Comments