Sometimes significant numbers have a seemingly mystical reason for being. In the case of Gloria Steinem, who turns 85 on March 25, and Diana Ross, who turns 75 on March 26, this feels true. Gender equality and racial desegregation have been the two biggest accomplishments of our lifetimes (there’s still a ways to go with both, of course), and exactly 50 and 60 years ago these two females took simple, random-but-destined steps that helped start those revolutions in the most real-deal, human way.

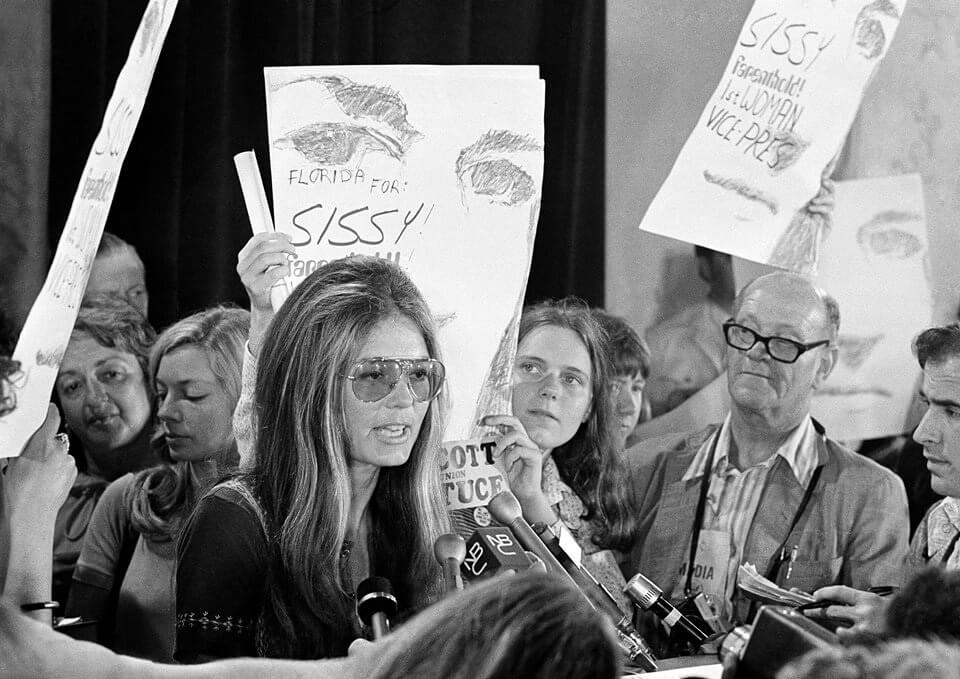

Gloria’s Awakening

Precisely 50 years ago—on March 21, 1969—Gloria, a hard-working writer and columnist for Clay Felker’s New York Magazine and a respected young woman about town, went to the Abortion Speakout in Lower Manhattan. Abortion was illegal, and the radical new feminist group, Redstockings, organized the event, during which dozens of women shared their powerful stories of terror, danger, and near death.

Betty Friedan had launched the substantial mainstream feminist movement in 1966 with her National Organization for Women, but, in these intense new counterculture years, Redstockings, New York Radical Women, and other groups now provided a revolutionary twist. Their members were not Friedan-influenced suburban housewives—who did a lot of good and made a lot of legal change—but, instead, hip younger women who had been militant activists in the Civil Rights and antiwar movements and who now were dismayed and angry that their “brothers” in arms—lovers! husbands!—were diminishing and humiliating them in ways they could no longer ignore.

The speakout gave the already politically minded Gloria a lifelong mission. She had been an earnest hard-working freelance journalist with a rare glamour: a mixture that that her roommate during those years—stylist,and soon-to-be overnight movie star, Ali MacGraw—recalled to me six years ago: “Gloria was always working, working, working at her little desk in the corner our apartment—and then she’d stroll across the room in a Pucci dress. She was a beautiful creature with so much substance and kindness, principled and consistent to the core. I knew back then that she was destined for great significance. And—this is important: She never sold herself out, never—and that’s decades of `never.’!”

She never sold herself out, never—and that’s decades of ‘never’!

At the March 21, 1969, abortion speakout, Gloria no doubt remembered the London doctor, Dr. John Sharpe (to whom she would heartfully dedicate her 2015 autobiography My Life On The Road) who had safely given her, at 22, the illegal procedure that enabled her to create her own future. The Redstockings event fired Gloria up with a passion to which she then dedicated herself, always collaboratively, for the next 35 years. She became the face of a feminism—a wise compromise between the NOW and Redstockings versions, largely by way of the magazine Ms., which her friend Felker previewed in his New York Magazine at the end of 1970 and which Gloria and others (Ms.’s editors were always a team of equals) launched as a stand-alone title in the spring of 1971. Ms. took off immediately. That feminism would go wide and deep and be permanent—and it would change America, giving mainstream women liberated lives.

Read More: From Dolly Parton to Diana Ross, the 2019 Grammys Were a Big Night for Women

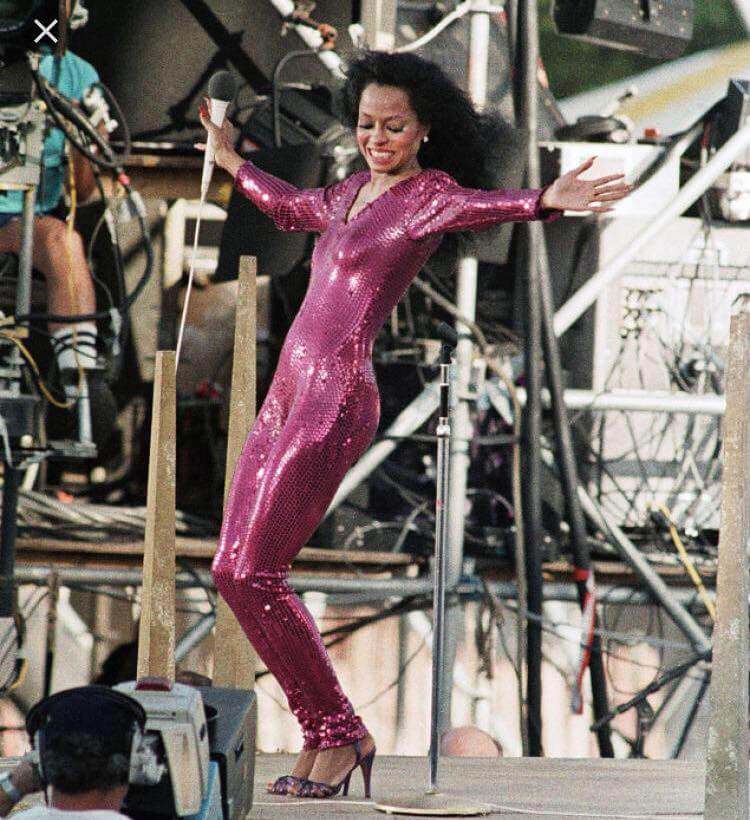

Ross Takes the Stage

Image: Diana Ross/Facebook

In 1959, precisely 10 years before Gloria’s awakening—exactly 60 years ago—15-year-old skinny, shy, good-girl Diane Ross (who soon popped an elegant “a” onto the end of her name, though most lifelong friends called and still call her “Diane”), formed a singing group called The Primettes with three of her neighbors in the all-black Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects in Detroit. Ross was a relatively new resident, with a fastidious mother and strict father. An older friend named William “Smokey” Robinson gave them a hand. In those staunchly segregated days, Diana was a proud black girl who loved singing Etta James’s “Dance With Me, Henry” and who revered Marian Anderson, Lena Horne, Ethel Waters, Dorothy Dandridge, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, Sarah Vaughn, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Diana had a light, high, calm, softly melancholic voice. It just happened not to be bluesy or, even though she sang in her Baptist church, gospel-like. She wasn’t supposed to be the vocal artist of the family. That role belonged to her adored older cousin Virginia Ruth. Diana’s family called Virginia “The Girl With the Golden Voice,” and Virginia planned to become a professional singer. But something horrible had happened. One night when she was driving back from Spelman College in Atlanta, where she taught, to her home in Bessemer, Alabama, Virginia was killed in a mysterious car accident. There were no skid marks and no marks on the car, and Diana and her family fully believed (and believe to this day) that her death was the work of the Ku Klux Klan. Diana would now carry on, in loving honor of her lush-voiced cousin.

Aside from the shocking death of her cousin, Diana personally experienced the ugliness of Jim Crow. When she and her sisters Barbara (who went on to become a renowned physician) and Rita took the Greyhound Bus to Alabama for summer visits, “we had to change our seats in Cincinnati,” she recalled in her 1993 autobiography, Secrets of a Sparrow. We had to “move to the back of the bus. When we stopped to use the restrooms we were forced the use the horrible and smelly areas marked `Colored’ and drink from the rusty and dirty water fountains.” The murder of Emmett Till was always on their minds as a warning, and the heroism of Rosa Parks was inspiration.

We had to move to the back of the bus. … and drink from dirty water fountains.

The 1959-formed Primettes soon morphed into the Supremes and were signed by a young musical entrepreneur, Berry Gordy, who insisted on the then-unheard-of idea that teenagers’ popular music need not be segregated into black radio stations, stars, and audiences and white radio stations, stars, and audiences. He further audaciously believed that African American groups could be, as his Motown label’s official saying went, “The Sound of Young America”—all of young America: black and white. The Supremes, who went on to break records with a dozen number one hits and become the best-selling female singing group in U.S. history, were at the forefront of this social, cultural, and natural integration among the teenage public. As the lead singer, Diana became the face of the transformation. There was a genuine sense of we are one generational unit, despite color. It was a new emotional reality for privileged white kids: more tantalizing and fun, less distant and obligatory, than their earnest appreciation of the Civil Rights movement.

Moving Mountains

Sometimes the symbolism of one person, coupled with hard work, risk and talent, is able to shift otherwise unmovable mountains and truly promote change. The undeniable—and well-tended—attractiveness of the 35-year-old Gloria Steinem, down to her distinctively streaked hair, her long, super-feminine fingernails, and her intentionally near-empty refrigerator (helpful in keeping her body svelte), shot down the sneering early-1970’s canard that these newfangled bell-bottoms-dressed females called “Women’s Libbers” were “ugly man haters.”

Diana Ross’s image penetrated suburban white teen America in the most organic and unpatronized way. Diana Ross had something that would later be, unimaginatively, called “crossover” appeal. When she burst on the scene with her Keane-painting-huge eyes (which happened to be Vogue-magazine chic then: think Twiggy and Penelope Tree), her high soothing voice, and those Courreges-like upscale luncheon dresses she was skinny enough to bounce around inside, singing lead on “Baby Love” and “Come See About Me,” white kids in the dreary suburbs they longed to escape developed a crush on her. They related to her. She wasn’t, to their provincial—and unintentionally racist—minds, “different.” The white girls wanted to be her; the white boys wanted to date her. She seemed a bit like Jackie Kennedy.

But hers was not a privileged or superficially won “crossover” popularity. As fantastically popular as she and the Supremes were, they faced danger when they played the South. “Sometimes we were afraid to get out of the bus,” she said. You could “just feel the bigotry in the air … slice it with a knife.” One harrowing night, a sniper shot at her and other Motown performers as they were leaving a Macon, Georgia, concert hall. They fell over each other running for safety back into the bus. And when, after she became famous, she got rightfully furious at a good ol’ boy racist who didn’t like seeing her and her white male manager, Shelly Berger, sitting together in a pizza place, Berger quickly rushed her out of the joint because he knew that—star or no star—“those guys were ready to rip us apart.” Still, later that night she and the Supremes performed in a “wonderful show with whites and blacks all having a good time together,” she reported, adding, “These awful things that happened did not change my love and respect for” people of either race.

One harrowing night, a sniper shot at Diana and other Motown performers.

Diana lived an integrated life. She would go on to have two very different white husbands: young, Jewish, New Jersey-raised music manager Bob Ellis (née Silberstein) and, years after her divorce from Ellis, Norwegian businessman Arne Naess. (She raised three daughters with Ellis–one of whom, Rhonda, was actually Berry Gordy’s biological daughter–and had two sons with Naess.) She lived in Beverly Hills and sent her daughters to Swiss boarding school and then to Brown and Georgetown universities.

But none of the privilege shielded her from the personal sensitivity of being a black woman in America. Her brother, she reports, once almost got killed for demanding change for a $10 bill when he bought a bag of chips at a restaurant. (“Somebody came from the back of the store with a knife and a policeman came and a shot grazed [her brother’s] ear.”) And, however much she embodied “too much” crossover appeal (white music critics will say that Aretha, with her soulfulness, was more “authentic” than Diana), nothing meant more to her than her depiction of Billie Holiday in 1972’s Lady Sings The Blues. Her portrayal was mind-blowingly authentic: the kind of authentic that comes not from acting lessons but from lived experience. She was widely expected to win the Oscar for the role, but Liza Minnelli, surprisingly, nabbed it for Cabaret. When Diana lost, someone very close to her at the time told me, she was absolutely bereft and she felt she left the “Strange Fruit” singer down.

Read More: A Mother/Daughter Team Spend One Fine Day With Gloria Steinem

Her Mother’s Keeper

Image: Gloria Steinem/Facebook

Like Diana, who represented young people’s social integration even while the most dangerous forms of official segregation was still flaring, Gloria Steinem’s presence as a figurehead (something she tolerated but disliked) was incalculably valuable. She made feminism relatable to heartland women who might have felt confused by and removed from “radicalism.”

But, despite her attractiveness and the elite New York media and intellectual circles in which she moved just before and during her feminism-stoking life, Gloria’s early years (like Diana’s life in the dangerous Jim Crow years) were not privileged—at all. She had an obese father with ever-tanking get-rich schemes and a peripatetic life that kept the family on the road much of the year. But he was also a man who believed deeply in his daughter, she would later, tenderly, say. She had a mother whose newspaper writing career was jettisoned by mental illness. Young Gloria became her mother, Ruth Steinem’s, caretaker, which helped lead to her to the decision not to have kids, she has said, though she deeply mentored many girls, including Alice Walker’s daughter, writer Rebecca Walker.

Life in 1940’s downscale Toledo, where Gloria grew up, was depressing.The factory workers cashed their checks for booze money that they spent in the tumbledown joints where Gloria sometimes tap-danced before she realized that a scholarship to Smith was a better way than showbiz to escape. In fact, it was so depressing that Gloria developed an intense aversion to any vistas (grass and trees) that reminded her of Ohio. For 25 years she refused to turn the concrete patch outside her New York apartment window into even a tiny garden! She didn’t buy that apartment until she was almost 50; she was too idealistic and cause-preoccupied to care about money or domesticity. She always kept an empty refrigerator while she wrote her feminist articles, always dashed to this political rally or that speech.

Gloria was too cause-preoccupied to care about money or domesticity.

She stayed financially precarious far longer than she needed to, rejecting any number of comfortable marriages because, like her early idol, Breakfast at Tiffany’s Holly Golightly, she didn’t think people should “own” one another. She wed South African businessman and animal rights activist David Bale—father of actor Christian Bale, in 2000 at age 66. She and David Bale loved each other—and he needed a green card. Tragically, he died of cancer three years later.

Everything was for women: all women. Despite criticism to the contrary, “the movement was multiracial from the beginning,” Gloria insisted, when I interviewed her six years ago. “I learned feminism from the National Welfare Rights Organization.” During those first five years, she appeared only in tandem with an African American speaking partner, activist Dorothy Pitman Hughes. That inclusiveness felt inviting to many, as did her communication style—calm and graceful with righteous outrage. How similar this was to Diana’s winning combination of ingredients.

The Legacies

With all of her many accolades and achievements, Diana was and is a mother before anything, people who know her say. She happily skipped the premiere of Lady Sings The Blues because of her advanced pregnancy with Tracee; she proudly introduced “my offspring!” at Las Vegas shows; she cried when her adult children came streaming onto Barbara Walters’s stage during a difficult time in her life. “She is a wonderful, protective mother,” says someone who has known her extremely well for decades.

Gloria and Diana have not had charmed existences, even after they became famous. Diana was arrested for DUI in late 2002 in Tucson while undergoing treatment at a nearby substance abuse rehab center. Just this past weekend Diana faced a tsunami of criticism for her controversial and likely imperfectly expressed tweet about Michael Jackson, whom she virtually discovered when he was a child singer with his brothers. “Stop in the name of love,” she said.

“Diana is tremendously and unequivocably against child abuse in any form,” said a close friend. Her tribute to Jackson (whose death in 2009 she wept over in anguish) was, this friend adds, merely “an act of love.” (She quoted her own and then Stevie Wonder’s song titles about “love” in two tweets.) It was not, this friend claims, a call to silence Jackson’s critics after the strong allegations that have emerged from the documentary Leaving Neverland, as many websites have claimed.

Gloria faced her own storm of criticism in early 2016, when Bernie Sanders was giving Hillary Clinton a run for her money. Gloria made a remark on Real Time with Bill Maher—one might say she was goaded into it by Maher—that made it sound as if she was saying that young women supported Sanders because their boyfriends did. A torrent of viral web headlines made our foremost supporter of younger women (Gloria has spent probably half of the last several decades talking with campus women) sound like a slut-shamer of Millennials. CNN’s “Gloria Steinem: Young Women Back Bernie Sanders So They Can Meet Boys” is just one example. They were nightmarish in their instant, though temporary, demolition of a person’s half-century-long reputation for holding precisely the opposite views, those which she has lived every day of two-thirds of her life.

A torrent of viral web headlines made Gloria sound like a slut-shamer of Millennials.

Today, thank God, with #MeToo’s boost, Gloria is in her amply deserved glory. Among other things, Gloria: A Life has been an off-Broadway hit. (It closes at the end of the week.)

Diana’s touring schedule is taking her everywhere from Las Vegas to New York in a few months, and there’s a film about her called Diana Ross: Her Life, Love and Legacy.

People don’t affect the culture unless they are truly of substance. Happy 85th, Gloria! Happy 75th, Diana! You changed our lives, and we are grateful for YOUR meaningful work at ages by which women were “supposed to” be retired. Now go and rock your milestone birthdays!

***

Sheila Weller is the author of seven books (three of them New York Times Bestsellers), the best of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—and the Journey of a Generation, which Billboard magazine recently named #19 of the best music books of all time. She has been writer of major features for Vanity Fair, a recent longtime senior contributing editor at Glamour, a has written for the New York Times Opinion, Styles and Book Review and for just about every women’s magazine in existence. She has won 10 major magazine awards.

0 Comments